When I first read Robert Kerbeck’s 2019 Malibu Burning — his first-person account of what is now known as the Woolsey fire — I underlined a sentence I found both slightly humorous and slightly disturbing: “Locals called it the YOYO Fire, for You’re On Your Own.”

Kerbeck explains YOYO in the first few pages:

A surfer buddy, Tim, once told me what gear to buy for the inevitable wildfire. A lifelong local, Tim had also warned me that there would be no firefighters when the time came, that if I wanted to save my place I would need to stay and fight for it myself.

Tim also

explained that the hydrant water would run out, so it was essential that I have a pump and my own water source. I glanced toward our hot tub and hoped it would be enough.

Surfer Tim proved prescient.

The fire that consumed Malibu started in Woolsey Canyon on Thursday, November 8 2018, from a downed power line.

By Saturday, driven by a hot, dry Santa Ana wind, it reached the ocean and Point Dume.

Point Dume is a place where, as a teenager, I sometimes hung out.

It’s also where Charlton Heston found the half-buried Statue of Liberty at the end of the first Planet of the Apes movie.

I tried to surf near the Point a few times, although I would not recommend it. The break is not great and there are some nasty rip tides.

Kerbeck relates the story of Judy and Brian Merrick, who had a house on Dume Drive and managed to save it by stamping out embers with their shoes. No firefighters in sight:

In the morning [Saturday], while their home was safe, houses all along Dume Drive were on fire. Still, there were no firefighters. Judy didn’t see any until late in the day on Saturday, over twenty-four hours after the fire had crossed into Point Dume.

Judy, Brian, and others put together at a local elementary school what became known as the Point Dume Relief Center:

After the no-show of the fire department, the locals realized that the cavalry wasn't coming to rescue them—or to feed them. The fire department hadn’t even allowed the Red Cross in, as the area wasn’t deemed safe.

The following Tuesday, Judy Merrick attended a press conference held by Malibu City Manager Reva Feldman.

By then, the residents’ biggest problem was the L.A. County Sheriff's Department:

…most Malibuites had seen no first responders during the fire. And now the first responders that residents were seeing were acting like the “gestapo,” as one city council member called them.

According to Kerbeck, the question Judy Merrick wanted to ask, but didn’t get a chance to, was:

Why was [Malibu City Manager] Feldman showing up only now?

Kerbeck relays Judy’s thinking. My emphasis:

Judy had a sense it had to do with the press being there; Feldman likely didn’t want to miss out on the chance to look good for the cameras, though no good look could exist for the collapse of an entire city government. Judy had expected failures during an event of the magnitude of the Woolsey Fire but not failures at every level: fire, police, all forms of government.

No government entity, as far as I know, is doing a comprehensive inquiry into the Los Angeles fires.

So in the spirit of YOYO, I suppose it’s up to me.

Nobody likes a Monday Morning Quarterback. I get that.

To which I’ll counter with a Japanese word: kaizen. The philosophy of making continuous improvements in working practices.

In a $52 billion disaster — or whatever it turns out to be — if you can make a small percentage difference, pretty soon you’re talking about real money.

Take, for a quick example, the ‘dry hydrant’ issue, which I’ll get in more detail to below.

The estimate of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (DWP) is that ‘only’ 20% of the hydrants in the Palisades area ran out of water, mostly those at higher elevations. At lower elevations, most hydrants worked, according to DWP.

A hard-ass boss would say — and I’ve had some — the acceptable number for that is 0%.

Clearly, not 20% of the homes that burnt in the Palisades would have been saved if there had been water in higher elevation hydrants.

But some would have.

Which is my point about kaizen. There’s no One Big Thing.

It was death by a thousand cuts, a totality of mistakes of in different sizes. I’m going to try to collect them into one place.

So I will be brave and ignore Substack’s length limit warning.

And update this post from time to time, as needed.

Which feels like the least I can do.

Many reporters are doing excellent investigative work on the fires, especially those at the L.A. Times.

But it’s the nature of newspaper stories to focus on one thing at a time.

When you put the puzzle pieces all together, the image that emerges is more disturbing: a Los Angeles smothered in a smog of institutionalized ineptitude.

There are notable exceptions, of course. A number of people and organizations, such as the Firehawk helicopter pilots, rightfully deserve high praise.

But official Los Angeles had its eye off the ball.

Or was watching the wrong ball.

Let’s start with the wind

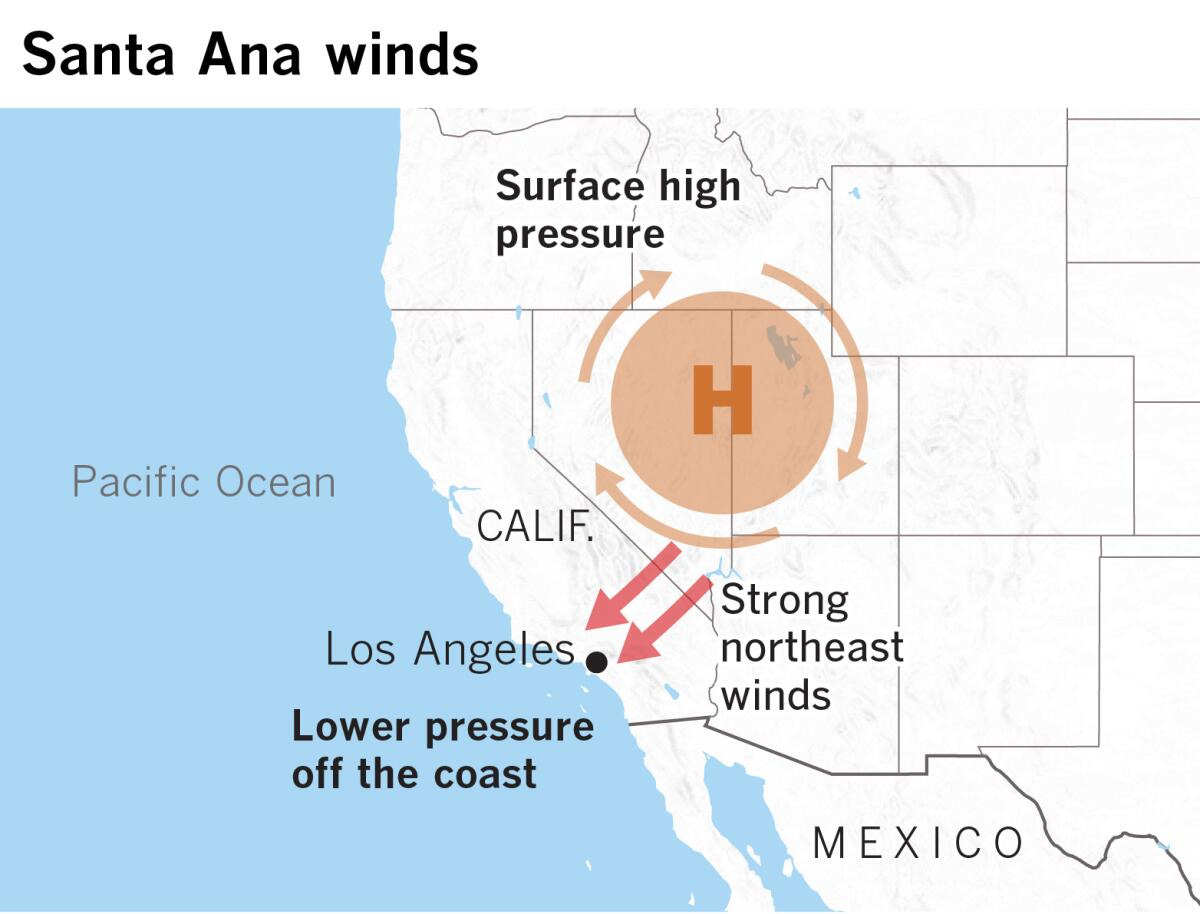

The hot, dry Santa Ana winds are a fact of Los Angeles topography.

That hasn’t changed in millennia.

Or decades. Raymond Chandler talks about them in his 1940s noir detective stories.

In 1969, essayist Joan Didion, interested in the folk wisdom that the Santa Anas can make people go crazy — or at least nervous and irritable — pointed out their similarity to other famous malevolent winds, such as Föhn of Switzerland and the hamsin of Israel.

That observation is correct, but her meteorology is technically not quite right. The Santa Anas are katabatic winds, which importantly relates to their dryness. In Southern California, unlike Switzerland, they’re not coming off glaciers.

The basic winter weather pattern that creates them is:

L.A. topography turns some of its canyons, especially those running diagonally northeast from the ocean, into wind tunnels:

It takes wind + ignition

A Santa Ana wind is a necessary — but not sufficient — condition for a bad fire in Southern California.

Over 75% of Santa Ana wind events generate no fire.

The additional necessary condition is ignition, as concluded in one 2021 study:

Temperature during the event and antecedent precipitation in the week or month prior play a minor role in determining area burned. Burning is dependent on wind intensity and number of human-ignited fires.

Here’s the link to that paper.

It’s an article of faith for some that climate change — not unlike the Hand of God in Medieval theology — can be seen in every disaster.

I have some complicated, nuanced views on climate that I won’t bore you with here.

But I’m happy to acknowledge that California’s climate has changed in the last century or so.

Just as long as the other baggage of the climate change orthodoxy doesn’t get pulled along with that.

In any event, it’s the Santa Ana wind, not global warming, that dries out the readily combustible brush in Southern California.

The Santa Anas can do that in as little as a few hours, which is why ‘antecedent precipitation’ was found to be a minor factor in the study mentioned above.

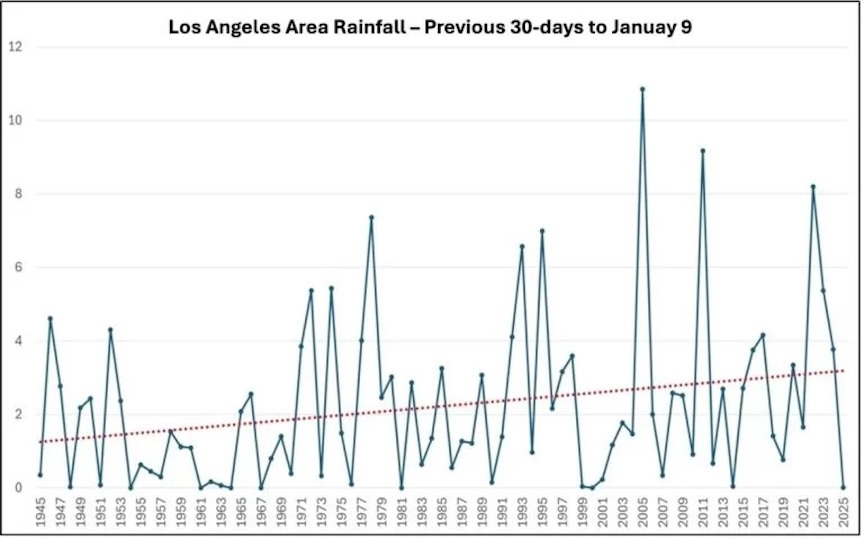

California’s climate has changed.

Which is important, but not for the reasons assumed by the climate faithful.

Expressed in math, California precipitation has changed in variation or volatility, but not much in absolute amount.

That’s been going on for a long time, a century maybe, and well predates the modern CO₂ scare.

Put graphically, the area under the curve, integrated over enough time, is the same, but the up-and-down peaks are more extreme:

The feast-or-famine nature of California precipitation was well understood by previous generations.

It’s why the reservoirs got built, and why the level of the Sierra snowpack is so important. The Sierras are California’s natural reservoir.

Aside: I won’t get into the state’s water wars. About water, let’s just say ‘catch it when you can’, an ethically sound principle, has at times morphed into ‘steal it when (or where) you can’.

A newly fashionable term, ‘whiplash weather’, basically sees the increased volatility in precipitation and adds worries about the vegetation cycle. A lot of rain one year can spur plant growth that can dry out and become fire fuel the next.

Fine. But not a terribly new observation. Mike Davis said that — and much more — in his 1998 classic Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster. Here’s a link to that on Amazon.

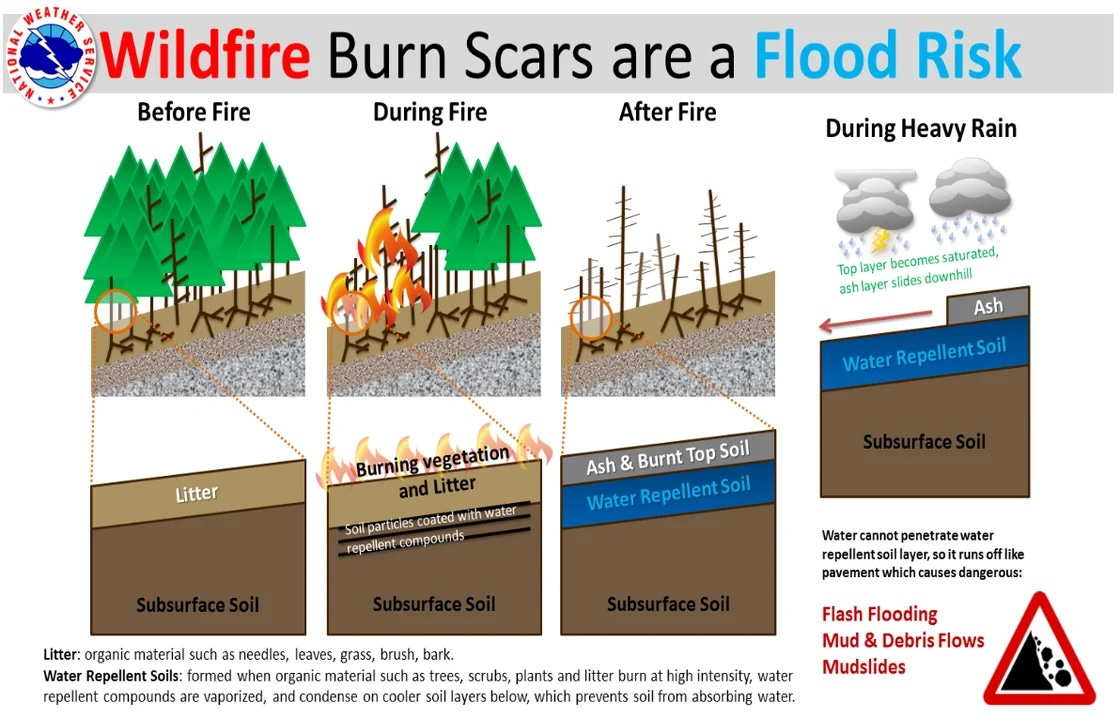

Being overlooked in the current moment is the possibility that the rain, if it finally does show up in Southern California in the next months, could be heavy enough that the runoff from the fire-burned areas will make for some nasty flooding and mudslides:

That flooding, too, would not be new.

The warning

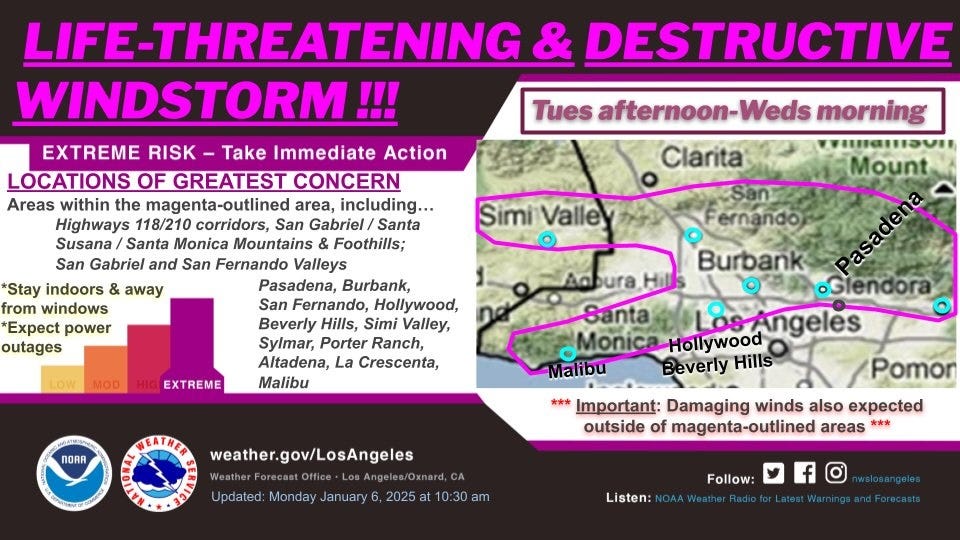

The Palisades fire flared up the morning of Tuesday, 7 January 2025.

The Eaton Canyon fire started early that evening, at 6:11 p.m.

There was no question that Tuesday would be what the Los Angeles Fire Department (LDFD) calls a ‘high-hazard day’. The National Weather Service—Los Angeles posted this on X on Monday afternoon at 1:00 p.m.:

Ignition

In California, power lines are — rightfully, but sometime wrongly — almost always the Prime Suspect for a wildfire ignition source, if there’s no stupid-human thing or arson as an obvious cause.

In what are called Public Safety Power Shutoffs (PSPS), a utility will intentionally turn off the power on its transmission lines — ‘de-energize’ them — in high fire risk areas when winds are bad.

That prevents bare wires — more on those below — from whipping around into contact with each other, which causes sparks, or from coming into contact with vegetation.

PSPS are politically charged in California.

No voter enjoys having his or her power turned off, especially if they don’t receive a warning or explanation.

Aside from being a nasty inconvenience for residential utility customers, power shutoffs cost business customers money.

One study — admittedly sponsored by Southern California Edison (SCE), and thus perhaps on the high side — estimated small or medium–sized businesses — all of them in the affected area — lose $21 per minute the power is off.

In January 2022, the California state legislature passed what was informally called the “shutoff reduction law”, which had the express intention of making Public Safety Power Shutoffs less frequent and harder for utilities to do.

PSPS were to be the last-est of last resorts.

That’s because the ‘Energy Safety Office’ of CPUC hates Public Safety Power Shutoffs.

According to the California State Auditor, it has called them ‘intolerable’, although I’m not sure if that’s his word, or one actually used by the Energy Safety Office.

They’re intolerable not because Energy Safety Office cares so much about utility customers being inconvenienced.

It’s afraid those customers might start using diesel generators during power shutoffs.

Which, of course, is contrary to California’s climate goals.

Burdensome paperwork is known to be an effective tool in any regulatory arsenal.

A utility that does a PSPS is now required to file a ‘post-event’ report with the California Public Utilities Commission, the CPUC, listing the alternatives it considered before it initiated the power shutoff.

It must also detail its thinking process in how it determined the benefits of the power shutoff outweighed ‘potential public safety risks’.

‘Public safety’ is one of those bureaucratic trump cards which, when played, squelches all further discussion.

Oddly, every police station, firehouse, hospital, and water pumping station actually looking out for the public safety knows it has to have a standby generator.

Utility electricity is just too unreliable. And getting worse.

I also suspect anyone at home with a medical condition that requires 24/7 electricity has already made some arrangement for backup.

To which it will be objected that some people can’t afford that.

After a quick switch to Google, I see Generacs selling at Lowe’s for $899.

For the ecologically-minded, it looks like you can pick up a Tesla PowerWall 3 for $9,500.

Perhaps one of those should be a standard MediCal benefit.

The cost would be a tiny fraction of the one coming due from the fires.

Palisades

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives is investigating the source of ignition of the Palisades fire.

If the ATF’s investigation of the August 2023 Maui fire is any guide, that will take some time. The ATF’s National Response Team issued its findings about the Maui fire in October 2024, over a year later.

But at risk of rushing the AFT to judgement, the ignition source of the Palisades fire is very likely to prove — a bit eerily — the same as that of the Lahaina fire. Here’s a link on the Maui one.

An earlier fire was thought to be out, but got reignited by the wind.

The Palisades fire started near a hiking trail, the Temescal Ridge Trail, which leads to Skull Rock, a popular destination for both respectable hikers and various ne’er-do-wells:

On New Year’s Eve, someone started a fire just west of the Trail when setting off fireworks.

That fire was put out, or so it was thought. These side-by-side photos were put together by the New York Times [link]. The ‘burn scar’ was left by the New Year’s Eve fire:

On the Tuesday morning of the Palisades fire, several people walking the Ridge Trail noticed some weird smokiness, but assumed it was the wind kicking up ash from the earlier fire.

The re-ignition phenomenon — noted in the 19th century by pioneers who swore prairie fires were traveling underground — is more common than thought.

It was the source of the Maui fire, which killed 102 people, and also caused the 1991 Oakland, California hills fire that killed 25.

The ‘nearby power poles’ are a complicating factor. The lines belong to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP).

It’s the LADWP’s stated policy not to shut off power to customers during dangerous winds: “the adverse impact on health, safety, and quality of life of its customers outweighs the perceived benefits derived from preemptive power shut-offs.”

Your CPUC Energy Safety Office at work. Although why the LADWP uses the word ‘perceived’ in that last sentence is beyond me.

But the LADWP told a Washington Post reporter the power lines near Skull Rock had not been live in five years.

If that’s true — I assume the ATF investigators will find out — that will get the LADWP off the hook.

Which will not be the case for Southern California Edison.

Eaton Canyon

The Eaton Canyon fire, which started on Tuesday, 7 January 2025, was pretty clearly caused by a large transmission line.

Matthew Logelin, who lives at the base of Eaton Canyon in Pasadena, heard a loud bang about 6:11 p.m. Tuesday as he was preparing dinner for his children, and called 911.

“It’s clear that’s where the fire started,” he said later. “It was right under the power lines.”

There are photos and videos:

Southern California Edison (SCE, sometimes ‘Edison’) owns the transmission line in question.

SCE lawyered up very quickly.

Which is entirely understandable, given California’s somewhat singular legal practice of holding utilities liable for the totality of follow-on damage caused by power line–sparked fires.

The November, 2018 Camp Fire, which killed 82 people in the Northern California town of Paradise, led within two months to Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. PG&E listed its potential liabilities in that filing at $30 billion.

On Thursday, January 9, SCE filed an Incident Report.

Taken literally, it’s probably all true:

To date, no fire agency has suggested that SCE’s electric facilities were involved in the ignition or requested the removal and retention of any SCE equipment.

But note that on Thursday the ‘fire agencies’ were probably too busy fighting the fires to get around to requesting the SCE equipment’s removal.

What has emerged since is:

The smaller power distribution lines that serve homes in Altadena were de-energized about two hours before the fire started.

The larger transmission line that runs down Eaton Canyon was not.

In an interview, the chief executive of Southern California Edison's parent company said that while power distribution lines that serve homes were de-energized about two hours before the Eaton Fire started, the transmission lines in Eaton Canyon were not shut off because those towers are stronger and can operate at heavier winds. Gusts in the region that evening approached 100 mph.

SCE says its telemetry shows no anomalies on its main line until well after the fire was established.

This one will head to court — if it doesn’t get settled first — where SCE’s lawyers will argue its side, and the trial lawyers will argue that of their Altadena clients.

The truth might come out in the courtroom fireworks.

But I wouldn’t hold my breath.

Ounces of prevention

Clearly, if those power lines had been underground, they wouldn’t have sparked in the high winds.

Likewise, they wouldn’t have sparked if the lines had been covered with insulation, which prevents them coming into contact with each other, or with vegetation.

Since 2016 or so, the CPUC has granted the state’s utilities large rate increases to finance various forms of ‘wildfire mitigation’.

Those costs now make up around 13% of customers’ monthly electric bills.

There’s also other state money going into this.

Putting power lines underground is expensive, between $2 and $4 million per mile, depending on terrain.

If California insists on having a gold-standard final solution to the utility line wildfires, the scale of the problem is enormous.

There are 277,000 miles of utility power lines in the state. About 54% of those are bare lines.

About 40,000 miles of bare lines run through areas Cal Fire rates as high fire-threat.

After some years of wildfire mitigation, only 27% of power lines in high fire-threat areas are underground or covered.

California voters — this is my opinion here — need to approve a very large, multi-decade bond issue to finance this, and stop trying to finance wildfire mitigation out of utility rates.

Which would have another big advantage: it would get the CPUC, which regulates the utilities, out of the picture.

On wildfire mitigation, the CPUC has been missing in action for the oldest of bureaucratic excuses, not really our department.

The CPUC, apparently, only works with paper. The utilities must deal with the physical world.

The CPUC’s job is only to see that the utilities have an acceptable ‘wildfire mitigation plan’ on file.

Unfortunately, the utilities know the CPUC is going to give them a pass on their plans.

The CPUC grades them using a number of very squishy criteria, such as an assessment of the utility’s ‘safety culture’.

According to a report by the State Auditor, the CPUC does not even go back and check to see if the utility actually did what it said it would do in last year’s plan.

Here’s the link to that report, number 2021-117 dated March 24, 2022.

The utilities are the ones who have to prioritize which lines to ‘harden’ and which to let slide.

One would think that top priority for lines to ‘harden’ would go to those most likely to create dangerous fires in the future. The classic risk equation is likelihood × potential impact.

I’m sure some of the utilities do this correctly in-house, on their own initiative.

Yet somehow a transmission line in a windswept canyon near a major population center didn’t get SCE’s attention.

Or did, and SCE made made a very bad miscalculation.

One problem is that the CPUC pushes an odd metric on the utilities, one that is backwards-looking and is only indirectly related to real-world fire risk.

The priority goes to lines that have inconvenienced customers with shutoffs in the past, not those potentially most dangerous in the future.

California’s bureaucracy generates a lot of paper.

It’s a fire hazard.

Astragalus brauntonii derails a steel pole solution

For smaller distribution power lines — as opposed to the larger trunk lines — a related option is to replace old wooden poles, which burn and fall down, with steel ones, which don’t.

Down power lines become a big thing during actual fires. Firemen are trained not to drive over them, since there is no way of knowing if they are live.

Robert Kerbeck quotes one of the L.A. Country Fire Department’s top commanders, Deputy Chief Vince Pena on this:

Pena explained how much time had been wasted trying to get resources into Malibu during the fire. Kanan Dume Road was the major thoroughfare that led into western Malibu, but it was closed due to the fallen poles. Resources had to be detoured down Malibu Canyon road, which had steel poles, and then up the PCH [Pacific Coast Highway], an additional forty minutes of drive time. Multiply that number by every trip first responders made, and an astronomical amount of time was lost; time that firefighters could have been saving homes. At the very least, Pena believed the poles on Kanan Dume Road should have been replaced with steel ones.

In July 2019, crews working for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) were replacing 200 wooden power poles installed between 1933 and 1955 in Topanga State Park with new steel ones.

LADWP used a bulldozer to clear and widen a graded road as part of a wildfire prevention project stretching from Pacific Palisades to Lake Encino.

That project came to a screeching halt when a concerned citizen discovered the bulldozer had taken out some stands of Astragalus brauntonii, common name Braunton’s milk vetch. Here’s a link.

Astragalus brauntonii is federally listed as endangered.

In an abundance of irony, Astragalus brauntonii is, according to its Wikipedia entry, “a short-lived perennial shrub with lilac flowers that is typically found on carbonate soils in fire-prone areas.”

It has beanlike seeds require scarification from fire or mechanical disturbance to break down their tough seed coats before they can germinate. The seeds persist for years in the soil until fire or disturbance allows them to sprout, with populations of the plant springing up in an area that has been recently swept by wildfire.

A relative of the Topanga kind grows in Baja. Wikipedia’s photo of that plant shows it growing in disturbed soil next to — guess what — a graded dirt road:

Another relative, the Humboldt milk vetch, Astragalus agnicidus, was thought to be extinct until 1989, when a passing bulldozer outside Phillipsville, Calif. disturbed some soil and its seeds sprouted.

Aside: Fire is a natural player in California ecology. The Giant Sequoia, for example, have evolved over millennia in the presence of fire. Its seeds, which can germinate years later, are sealed in the pine cones by a resin that melts only when exposed to high heat.

Fire detection

Luckily, both the Palisades and Eaton fires were reported quickly.

That didn’t have to be the case.

There’s an interesting technology for fire detection that uses a face-recognition-style AI to bring possible fire starts to the attention of human monitors in a control room:

The AI is usually faster to spot a fire than 911 callers, but false alarms can be seriously expensive. Humans are necessary to make the final call.

ALERTCalifornia is a University of California at San Diego project that’s been evolving for several decades. It started out doing seismic monitoring but later branched out into fire-spotting, especially in remote areas.

As of 2023, it had 1,060 monitoring cameras and sensor arrays installed across California. A two-camera system is commercially available from a Chico, California firm, ALERTWest. Here’s a link.

There are actually a number of ALERTCalifornia cameras in Southern California, including one operated by Southern California Edison.

But there probably needs to be a lot more, especially in the more remote canyons.

Rapid response, or lack thereof

A Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD) operations publication states:

Our first-alarm brush response is based on a ‘hit it hard and fast’ concept. … If it is a high-hazard day, (fire) companies will be pre-deployed.

As von Moltke said, no plan survives contact with the enemy.

Rapid response - by air

The obvious best way to put out new fire is to dump a lot of water on it quickly, while it’s still small. Or dump a lot of water plus retardant just downwind, to pen it in.

Speed and water carrying capacity are of the essence.

For fires breaking out in the canyons, that means an air drop. The New Year’s Eve Skull Rock fireworks fire was put out — sort of — by helicopter drops.

Ideally, on a high-hazard day, you’d want a flight line of helicopters (the S-70A Firehawk is one) loaded and ready to go.

Fixed-wing aircraft have greater carrying capacity, but the drops are not as accurate.

The pilots are legitimate heroes of this story. Those same gusting Santa Ana winds — coupled with unpredictable up- and down-drafts from the fire itself — made flying over the fires dangerous.

The New York Times ran an excellent story about a helicopter pilot who happened to be in the air with a load of water and tried to get it on the Eaton Canyon fire after dark on the Tuesday. He came with an inch of crashing. The link is here.

After the fires get established, of course, the air drops still make a big difference. They saved Brentwood when the Palisades fire was headed its way. [Link]

The ‘pre-positioning’ controversy

If the helicopters can’t fly, the next best option is a fire truck with a load of water.

That was a road not taken, at least according to the L.A. Times: “L.A. fire officials could have put engines in the Palisades before the fire broke out. They didn’t.” [Link]

No one is going to criticize a fire chief for not guessing correctly where a fire is going to break out.

Although there’s technology — not used — that could have helped make that decision.

Ting sensors are bought by homeowners and plugged into an AC outlets:

They are normally used to detect voltage irregularities that may indicate the wiring in the house needs fixing.

But when there are enough Ting sensors in an area, that data collectively says a lot about the local electrical grid.

When the wind is whipping around the power lines, it generates lots of little but detectable voltage irregularities.

In Altadena — downwind from the Eaton fire — 317 grid faults were detected in the hours before the ignition. Normally, there are very few faults.

The utilities, such as SCE, presumably have comparable or even better data.

But California liability law makes them reluctant to share it. Trial lawyers will present it to some jury as a preemptive confession. They knew, or should have know, etc.

As with video AI fire detection, a ‘filter room’ with the skill process raw data is a critical component. That was one of the under-appreciated discoveries of the British when they deployed their early radar system prior to World War II.

Given the severity of the weather warning, one would assume the Tuesday of the fires would have been an all-hands-on-deck day.

For the Los Angeles Fire Department, somehow, it wasn’t.

That’s based on looking at the number of (a) firefighters and (b) fire engines that were ready to go, compared to number that could have been.

The details, as reported by the L.A. Times, (link) are complicated, but:

The department only started calling up more firefighters and deploying those additional engines after the Palisades blaze was burning out of control.

LAFD Fire Chief Kristin Crowley gave a reaction to the Times story. But allow me to add an emphasis:

Fire Chief Kristin Crowley defended her agency’s decisions, saying that commanders had to be strategic with limited resources while continuing to handle regular 911 calls.

“Regular 911 calls” needs expanding. What are those?

In the first half of 2024 (up to August) the Westlake Fire Station 11 — whose area admittedly includes sketchy MacArthur Park — made 36 runs for structure fires as opposed to 599 drug overdose calls.

In 2023, the city had a pilot program that sent mental health workers instead of firefighters out on non-emergency 911 calls in a special ‘therapeutic van’.

Fire and ambulance crews were spending too much of their time being Door Dash for naloxone. The idea was to free them up.

LAFD firefighters are represented by two strong — and politically potent — unions.

The pilot project, not unpredictably, got the kibosh.

Those mental health workers were ‘insufficiently trained’. Not strong enough to wrestle those overdosing drug addicts into the van, and so on.

For 2022, LAFD officials said their records showed 64 employees made over $400,000 in salary, overtime, and other pay — not including benefits. Several of the captains made more than $500,000.

Alert system failures

On Wednesday [23 January 2025], the lead story on the front page of the L.A. Times ran under the headline “Alert came hours into blaze.”

After reading it, I conclude the old 1950s civil defense air raid sirens had something going for them.

For government agencies, sending out emergency alerts by wireless no doubt sounds very with-it and high tech. You’ve got the Amber Alert-style warnings that can be sent to cellphones, and federal government’s Wireless Emergency Alert system, known as WEA.

But when people have their power out, as most did in Altadena, their cellphones, internet routers, and laptops are living on borrowed time.

As are, I assume, the local cell phone towers. Signals will be nonexistent or spotty.

Not everyone, of course, sees those messages.

Or should. On the Friday, erroneous evaluation notices were sent out to thousands of people nowhere close to any fires.

The wireless notification system in Altadena also failed to cross over that community’s historic racial divide, North Lake Avenue.

In the bad old days, Lake Avenue was one of those infamous 'red lines' used by mortgage lenders to sort minorities to the west, others to the east.

Altadena neighborhoods west of North Lake Avenue did not get electronic evacuation orders until 3:25 a.m. Wednesday, well after structure fires were burning there.

Those east of North Lake Avenue received evacuation orders more than 10 hours earlier, at 7:26 p.m. Tuesday.

In was not until 2 a.m. Wednesday that Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department patrols started driving down streets in west Altadena using bullhorns to urge people to evacuate.

All of the 17 confirmed deaths in the Eaton fire were in west Altadena.

Dry hydrants

A fire truck, of course, carries only so much water.

In the Malibu fire in 2018, as in the recent ones, some fire hydrants went dry.

The pertinent quote here is from Marty Adams, a former general manager and chief engineer at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

The pump-and-storage system was designed for a fire that might consume several homes, not one that would consume hundreds.

“If this [the January fires] is going to be a norm, there is going to have to be some new thinking about how systems are designed,” Adams said.

I couldn’t agree more.

Three gravity-fed water tanks near Palisades were duly topped up prior the blaze. They hold 1 million gallons each. Here’s the map;

The missing piece in that puzzle is Santa Ynez Reservoir. It was empty in January, and had been since February 2024:

Santa Ynez holds 117 million gallons. Compare and contrast with the 1 million in each of the three water tanks.

The LADWP emptied the reservoir after it found a several-foot-long tear in its floating cover. The tear might allow “debris, bird droppings and other objects” to enter the water.

The image of a few bird droppings in the water is definitely icky, but we are talking about 117 million gallons here.

The LADWP’s employee union said the tear was minor and offered to do the repair in-house, presumably for a bit of overtime.

Instead, the Department put out the job out for bid. After many delays, it eventually accepting one for $130,000 in November.

One year on, the repair still hasn’t been made.

The idea that a municipal reservoir needs a cover at all is, by the way, a relative recent manifestation of our contemporary chemphobia.

Santa Ynez didn’t have one until 2012. Here it is before:

So maybe — before fire season — you could just keep it filled whether it had a tear in the cover or not. Worked between 1968 and 2013.

There are a number of ways to disinfect drinking water, including UV light, but following the conventional treatment process, chlorine and ammonia (nitrogen) are added to the water to form chloramine, which is a disinfectant that stays in the drinking water.

Chloramine is EPA-approved, but in 2005, the EPA decided to crack down on chemical byproducts of the disinfectants that can be produced in exposure to sunlight.

I assume EPA science found that massive doses of those byproducts could create cancer in rats, or something.

Which, if true, means the generations who’ve been drinking chlorine-treated water for decades are in for big surprise.

The LADWP, in an abundance of caution, decided to put covers on all its reservoirs.

Which was probably less expensive than getting into a fight the Feds.

In any event, Santa Ynez was missing in action.

On Friday 10 January 2025, California Governor Gavin Newsom sent a letter to leaders of DWP and L.A. County Public Works asking for an explanation for the loss of water pressure and the empty Santa Ynez Reservoir. Newsom called “deeply troubling.”

Hydrant pressure was only one thing.

The reservoirs played a different, and more vital, role in fighting the fires. They were the water source for the helicopters and ‘Super Scoopers’.

Santa Ynez would have been much closer in flying time to Palisades than, for example, the Encino reservoir, which got a lot of use.

There’s a fascinating animation on X concocted out of flightradar24 data showing helicopters flitting back and forth to the Encino reservoir like a bunch of busy bees.

I always thought — still do — Robert Kerbeck’s book would make a great TV series.

It has the right structure. Each short chapter is focused on the response to the fire by the some different slice of the Malibu community.

And, it has animals.

Which would give it some kids appeal, and great visuals.

I can picture this scene from my old hangout, Zuma Beach: “Seeing large animals like alpacas and llamas walking on the sand was breathtaking, as if a zoo had burned down.”

That was according to Jennifer.

Katie “saw the same horses, donkeys, and llamas that I did tied to lifeguard towers. They’d been evacuated by their owners, who had spent the night in their nearby cars.”

In my mind, Malibu Burning — the miniseries — would be welcome antidote to CBS’s soap opera Fire Country, which delights in the quasi-militarized culture of Cal Fire.

In many Fire Country episodes, it’s those damn civilians — the hikers, homeowners, and so on — who are the panicked idiots who need take orders from the trained professionals.

Military cultures, however, also become a haven for complacent ‘lifers’. The ones who have learned to get by exercising a minimum of effort.

Lifers also exist in state and local bureaucracies, and political life.

From time to time, the deadwood needs to be cleared.

Just saying.