Hamilton's Start-Up

Inventing industrial policy.

In 1987, British military historian Paul Kennedy published The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000.

It seemed a bit odd for a military historian to concern himself with ‘economic change’.

The answer could be found by a glance at Kennedy’s previous book, The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860-1914. The naval arms race between those two countries prior to World War I was premised on steel, the prerequisite for building the massive Dreadnought-style battleships of the day.

Germany (as did the U.S.) underwent almost astonishingly rapid industrialization in the last few decades of the 19th century. Germany’s production of steel surpassed that of Britain in 1895.

Kennedy’s point in The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers was that “all of the major shifts in the world’s military-power balance have followed alterations in the productive balances.”

Kennedy (still alive, age 87) originally planned to publish The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers the year before, in 1986.

But he decided to take some more time and add a chapter at the end with some predictions, and precautions, for U.S.

Aside: A decision he came to regret, mildly. “[Rise and Fall] was actually a study of more than 500 years of global empires,” he told an interviewer later. “But I don't think many people read more than the final chapter on the U.S.”

Kennedy cautioned that ‘imperial overstretch’ might catch up with the U.S. of the 1980s. Ronald Reagan was then trying to outspend the Soviet Union on things like the ‘Star Wars’ anti-missile program.

Kennedy also predicted it was ‘only a matter of time’ before China became a great power.

After 1987, Kennedy’s points got lost.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 led to a brief decade of triumphal thinking in West.

The United States was the sole superpower left standing.

The new ‘unipolar’ world, under its guidance, would enjoy a era of peace and prosperity comparable to the Pax Britannia of the 19th century.

That didn’t last.

After 9/11, ‘imperial overstretch’ returned to mind. The cost to the U.S. of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan approached $6 trillion.

And the ‘matter of time’ it took China to become a great power proved much shorter than anyone imagined.

The rivalry between the U.S. and China has become the great power contest of our time.

It has been, blessedly, so far confined to the economic realm.

This is the second of two posts inspired by the US-China trade war.

The first looked tariffs.

This one looks at industrial policy.

There was no simple answer about whether tariffs are ‘good’ or ‘bad’.

In economic theory, tariffs are almost always ‘bad’. They increase costs to consumers.

Here’s a New York Times headline from April 2015: “Economists Actually Agree on This: The Wisdom of Free Trade.”

Yet historically, high protective tariffs were the norm for the United States from 1816 to 1945.

The U.S. economy had some up and downs in those years, but it did okay.

Something needs explaining.

Were earlier generations of American politicians unenlightened? Were they in the grip of special interests? Maybe just plain dumb?

The tariff debate is one of the oldest in American history. In my piece on the tariff, I tried to use actual voices from it.

Whatever they were, they weren’t dumb.

My modest suggestion: ignore academic economic theory.

Or, more precisely, what the rest of the world calls ‘Anglo-American’ economics.

First off, it’s a value system.

Although a well-disguised one. Its concepts have come to permeate our thinking.

But, as with an Orwellian Newspeak, that limits our range of thought. It does not extend it.

Some of the concepts of academic economics sound great.

Take ‘efficiency’.

Who can be against efficiency?

But academic theory has always been a bit murky about who all, exactly, benefits from all that efficiency.

There’s ‘Pareto optimality’. Optimal how? The ‘optimum’ is just a nodal point produced by a mathematical equation. Calling it ‘optimal’ sneaks in a whopping value judgement.

Second, Anglo-American economics tends to work by deduction from first principles.

Let’s pick two: the (1) desirability of consumer welfare and (2) Adam Smith’s concept of comparative advantage.

Aside: An emphasis on consumption, as opposed to production, as the best measure of how a society is doing follows from a different bit of theory: point of having production in the first place is to enable its ultimate consumption, so why cut downon the number of variables and just use it?

If we follow the chain of deductions to the end, we can get results that are certainly intellectually provocative, but progressively unmoored.

Consider this one on the merits of free trade:

Competition is good. It kills off overpriced producers.

Killing them off is good, because more efficient suppliers will give the consumer a better deal.

Unrestricted foreign trade is best of all, since it allows the most efficient suppliers in the entire world to compete.

It doesn't matter why competitors are willing to sell for less.

They may be genuinely more efficient. Or they may be willing to sell below cost for reasons of their own.

In either case, the consumer is better off.

Thus if Chinese manufacturers are selling solar panels below their manufacturing cost (an empirical proposition ‘not proven’, despite what the U.S. Trade Representative says), we should thank them and buy all the panels we can get our hands on.

In 1979, Milton Friedman, who won the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize for economics and was definitely something of a provocateur, coined a term for this: ‘foreign philanthropy’. Friedman advised taking advantage of it while it lasts:

If foreign governments want to use their taxpayers’ money to sell people in the United States goods below cost, why should we complain? Their own taxpayers will complain soon enough, and it will not last for very long.

The ‘historical school’ of economics is an alternative to deductive economics.

Like history, it gets a bit messy. It’s inductive. Not so logical and neat.

Jettisoning ‘Anglo-American’ economics may sound unpatriotic.

But the patron saint of historical school is our own Alexander Hamilton, so no worries there.

Hamilton himself decided to ditch the theories of Adam Smith, the Anglo-American economist of his day.

To run the pertinent stream of economic history backwards: we have China today; Japan, South Korea and Taiwan after 1945; and, in the 19th century, Meiji Japan and Prussia.

All leading back to the fount, Alexander Hamilton.

The American War of Independence was the first successful anti-colonial war.

Something the world hadn’t been seen before.

Colonies, from the beginning, were meant to be subordinate to the economic and monetary interests of the mother country.

‘Colony no longer’ raised a question: Now what?

The young United States had an opportunity to re-invent itself.

If it wanted.

One option was to continue the old colonial economic relationship with Britain, just under the new country-name rebranding.

That’s what the Southern agricultural faction in the U.S. expected to happen.

They’d go on growing cotton and tobacco (with slave labor — I am aware) and trade it for any British-manufactured items they needed.

Agriculture was obviously the future of the United States. There was so much land available.

Aside: Yes, I know. After ‘stealing’ it from the Indians. European settler societies have a lamentable track record in dealing with people living on land they coveted. Add South Africa, Australia, and Israel to a long list.

Jefferson took it a bit farther. Agriculture should be the future of the United States. Independent yeoman farmers would be the moral backbone of the new republic.

A Northern and urban faction had a more expansive idea of what independence from Britain would require. New England had been starting to act more like a competitor to England than a subordinate partner.

Independence for shipping and commerce meant the new nation would have to have its own navy. The young United States was a bit slow off the mark on that.

Making the overall U.S. economy independent was a very hard ask.

Intellectually, it required inventing a theory in of development economics.

Which is what Alexander Hamilton did.

One great power conflict, the one between Britain and France, was settled at Waterloo in 1815.

The Duke of Wellington famously called that battle “the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life.”

Another near-run thing was the outcome of the American War for Independence.

Which can be viewed as a major sidebar in that same decades-long Anglo-French conflict.

There were as many French regulars as Continental soldiers at the deciding battle at Yorktown in 1781.

And it was the French fleet on the York River that had trapped Cornwallis.

In John Trumbull’s The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis, now hanging in the Capitol Rotunda, the surrendering British officer, General Charles O'Hara, rides out between the French on the left and the Americans on the right:

Hamilton is in the painting. He had been in the battle.

Had he not been, Hamilton would be a footnote in American history. We’d have been deprived of an entertaining Broadway musical.

Hamilton spent four years as George Washington’s invaluable number two, effectively his chief of staff.

Hamilton was a super-competent aide de camp.

And, thanks to his Huguenot mother and boyhood in the (British) West Indies, he was comfortably fluent in French. Washington didn’t speak the language, and considered himself too old to learn.

When France came into the war, Hamilton was an essential go-between, a nexus.

But as staff officers do, Hamilton itched for a combat command.

As the plan to trap Cornwallis evolved in early 1781, Yorktown looked to Hamilton like it might be his last chance to see action.

Hamilton lobbied Washington hard. He threatened to resign his commission. He made a nuisance of himself.

Washington had near-paternal affection for his ‘family’ of aides.

His apprehensions about losing them were not without foundation.

Officers led from the front in those days. Under fire, the ‘code’ called for them to display a cool disregard for their personal safety.

Washington lamented the deaths of several of his young officers who exhibited “intrepidity bordering on rashness.”

Hamilton’s best friend, John Laurens, was senselessly killed in August 1782 when, against orders, he led charge into a waiting British ambush. Laurens appeared destined for great things. His rising political star may well have outshined Hamilton’s.

Washington finally relented and put Hamilton in charge of a New York battalion of light infantry.

On October 14, 1781, after yet more lobbying, Hamilton led that battalion in a night-time, bayonets-only capture of British Redoubt No. 10.

Hamilton was lucky. The French battalion that stormed Redoubt No. 9 took heavy casualties.

In the event, Hamilton was made.

“At Yorktown,” Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow writes, “Hamilton established his image as a romantic, death-defying young officer, gallantly streaking toward the ramparts. Take away that battle and Hamilton would have gone down as the most prestigious of Washington’s aides, but not a hero.”

Hamilton had extraordinary self-discipline and a prodigious capacity for what we now call ‘self-directed’ study.

As a teenager in the West Indies he read deeply, if eclectically.

When Hamilton arrived in New York in 1772, he talked the president of King’s College (later Columbia) into letting him make up the formal deficiencies in his education with a self-study program.

That took him a little over two years. Hamilton was just finishing up when British troops arrived in New York.

Hamilton’s student anti-British speeches and newspaper articles thrust him on the political stage for the first time. Hamilton also organized and drilled a student militia troop.

Hamilton was soon recruited to serve as a private secretary for Washington. Most of Washington’s wartime letters and written orders are in Hamilton’s hand.

Hamilton’s mother had put him out to work at age 12 in an import-export firm in Nevis. He was well-organized and good with figures.

Hamilton soon got involved in the difficult business of obtaining provisions for the Continental army.

Washington wrote at Valley Forge in February 1778, “For some days past there has been little less than a famine in the camp.”

Almost a quarter of the army, some 2,500 men, perished from disease, famine, or cold. The snow was stained with blood from the bare feet of the Continental soldiers.

Boots, tents, blankets, muskets, and gunpowder were ‘manufactures’ that had previously been imported from Britain. They were in perennial short supply.

Food was a different scandal. Soldiers were dying of malnutrition while encamped in the middle of fertile American farmland.

That, in part, was because farmers and merchants refused to take the paper currency and IOUs issued by the Continental Congress and the various States.

They could do much better selling to the British in nearby Philadelphia. The British also paid in paper currency, but it was good for ‘specie’, gold or silver coin.

Continental soldiers were forced to take their pay in IOUs.

They did more than grumble about that. Desertion was common. On several occasions there were near-mutinies.

The sorry situation prompted another one of Hamilton’s self-study bouts. He read everything every European writer had written on the theory of money and banking.

He developed a mentor-mentee relationship with wealthy Philadelphian Robert Morris, the ‘financier of the Revolution’.

In 1781, Morris started the Bank of North America in an effort to fix the Continental paper currency problem. Hamilton helped Morris write the plan for that bank.

During the War, in 1780, Hamilton married well, to Elizabeth Schuyler, the second daughter of Philip Schuyler, a wealthy upstate New York landowner. Philip Schuyler was one of Washington’s Generals.

The Schuylers were a old-line New York Dutch family. Elizabeth’s mother was a Van Rensselaer, as in the polytechnic institute in Troy, New York.

A parvenu is a person of ‘obscure origin who has gained wealth, influence, or celebrity’.

Hamilton’s origins were not obscure, but he was legally illegitimate. And he had been ‘in trade’, a merchant.

Certain society snobs sniffed.

What mostly bothered them was that the American Revolution, as revolutions do, had raised up some ‘new men’. And tossed down a few others.

Hamilton was one of Washington’s dashing young officers. That was good enough for Elizabeth Schuyler.

The couple, by the way, had eight children and a largely happy family life, if marred by an infidelity on Hamilton’s part revealed in a very public political scandal.

Elizabeth lived into her 90s. She was a ‘famous widow’ in the Washington, D.C. of the 1850s, the last link to the Founders.

Hamilton’s combative, ‘outsider’ psychology makes good material for a musical.

But, in fact, Hamilton slotted easily into New York’s post-War financial and legal elite.

Hamilton passed the New York bar after one of his self-study bouts. That one took six months.

Most of the Founders had ‘read’ the law, but as a prerequisite for going into politics.

Hamilton actually was a practicing lawyer. That’s important in appreciating his ‘realistic’ — some would say ‘compromised’ — approach to issues.

Chernow, I believe, somewhere puts it nicely: Jefferson wrote the poetry of the American Revolution. Hamilton, the prose.

Hamilton’s ‘network’ was large. It included his fellow officers from the war. And, of course, George Washington. Those even had a fraternal organization, the Society of the Cincinnati.

In 1784, Hamilton’s brother-in-law, John B. Church, had the idea of starting what became the Bank of New-York.

As the lawyer-organizer, Hamilton ended up taking some founders’ shares. He also became one of its directors.

One of Hamilton’s many friends — Alexander McDougall, a former fellow officer and Society of the Cincinnati member — became the Bank’s president.

The Bank of New-York would become throughly entwined in the finances of the new federal government after Hamilton became Secretary of the Treasury.

Despite being a parvenu — or possibly because of it in some reverse-psychology way — Hamilton was most definitely an elitist.

It’s worth trying to make the case in his defense.

To his credit, Hamilton favored the abolition of slavery and the end of the slave trade.

Among the other Founders, only John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, John Jay and Governeur Morris had comparable views.

The Founders had all read the classics of political theory. Those started with Plato and Aristotle.

For the Founders, the philosopher’s question “What is the best form of government?” was not an intellectual speculation. It was an operative choice, one they had to make.

Direct democracies and republics, the philosophers all held, could fall victim to ‘excess’ democracy.

They could degenerate into ‘mob rule’. Or the dêmos could fall for a demagogue and elect a dictator.

The Founders limited the franchise in their new republic to propertied white men.

As for having an ‘aristocracy’, America would try to avoid developing a hereditary one.

The literal meaning of ‘aristocracy’ is neutral: ‘rule of the best’.

The new republic would draw its best from the educated and propertied classes, on the basis of merit.

It was, additionally, hoped — for a time around the Revolution anyway, the idea didn’t last — that the best would display the non-partisan, disinterested public ‘virtue’ of the great figures of Roman Republic, such as Cicero and Cincinnatus.

Hard as it may be to appreciate today, Hamilton had that.

In his five years as Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton displayed the probity and financial rectitude you would expect from a Swiss banker.

The system — including parts of it Hamilton designed — may have benefited the mercantile elite of which Hamilton was a part.

That was controversial enough in the politics of the day. But Hamilton didn’t profit personally.

In 1795, after he announced he intended to resign as Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton wrote a letter to his sister-in-law in which he joked about how he would be leaving public office poorer than he went in.

He estimated it would take him 4 or 5 years back working as a New York lawyer to get his family’s finances in shape.

The political muckraking of the time was positively vicious. If there had been anything ‘there’ there to find about Hamilton, presumably somebody would have found it.

By our standards, a remarkable figure.

When Congress met for the first time in 1789, it had to play fill-in-the-blanks with the Constitution.

Article 2 had vested executive power in “a President of the United States of America.”

That one was easy: George Washington.

The Constitution had little to say about what the rest of the executive branch should look like.

After the usual drawn-out debate, Congress created three departments: State, War, Treasury.

Thomas Jefferson, newly returned from Paris, would be Secretary of State. Henry Knox, one of Washington’s former generals, would be Secretary of War.

Washington’s first choice for Secretary of the Treasury was Hamilton’s former mentor, Robert Morris, financier of the Revolution.

Morris declined and recommended Hamilton instead.

Hamilton took the job in September 1789. He started right in.

Conflict of interest wasn’t much of a thing in those days.

Two days after becoming Treasury Secretary, Hamilton arranged a loan to the new government from the Bank of New-York.

That loan, and subsequent ones, paid among other things the salaries of George Washington and Congress.

The first Congress operated in ‘100 days’ mode. Everything had to be invented from scratch, all at once.

Fortunately, Hamilton had phenomenal energy. And his famous ‘plans’ at the ready.

The American economy was in miserable shape during the Articles of Confederation years, 1781-1789.

There had been a momentary boom at the end of the war when trade resumed with Britain.

After that, it was all downhill. The depth of the depression, percentage-wise, was comparable to that of the 1930s.

Economists still debate the causes of the Great Depression.

The one from 1781-1789 was clearly monetary in nature.

There wasn’t any. Or much.

‘Real’ money was silver or gold coin, ‘specie’.

One goal of British mercantilism had been to manage trade with its colonies so that silver and gold accumulated, and remained, in the mother country.

It was mostly still there.

The fundamentals of the American economy were sound.

That is to say, agriculture. In the South, people used warehouse receipts for tobacco as paper currency.

Farmers might have wealth, as in land, but had trouble laying their hands on money.

They could, of course, always barter.

On 2 January 1779, Abigail Adams wrote her husband about the household accounts:

I have not a single six pence can I get of substantial coin. … Remittances made in goods … will fetch hard Money ….

Farmers with bank loans and back taxes couldn’t come up with enough ‘specie’ to make their payments.

Shay's famous rebellion (1786) is commonly misconstrued an attempt to overthrow the government. It was actually an attempt to close a country courthouse so it couldn't issue bankruptcy writs and foreclose on farmers' land.

The U.S. government under the Articles of Confederation was also a deadbeat. The Continentals had received loans from France during the War.

Congress stopped making interest payments on those in 1785. Two years later it gave up pretending to pay at all.

Like someone using a cash advance on one credit card to pay off another, Congress kept current only on the loans it was getting from the Dutch. Amsterdam was the one place remaining where it still might get future ones.

To appreciate Hamilton — and aspects of later economic development in Asia — we need to abandon some our contemporary shibboleths about merits of ‘innovation’ and demerits of ‘copying’.

Steve Jobs said — at least in the 1999 TV film Pirates of Silicon Valley — "Good artists copy, great artists steal."

The original quote, from Goethe, is more insightful. In 1827, talking about the workshop training system of Renaissance artists, the German poet said “If you see a great master, you will always find that he used what was good in his predecessors.”

As the first Treasury of the Secretary, Hamilton produced a triad of enormously consequential reports, his famous ‘plans’.

The first and most important was Hamilton’s plan for dealing with the Revolutionary War debt. That was laid out in his January 9, 1790 Report on the Public Credit.

The second was his plan for a National Bank. That was submitted to Congress on December 14, 1790.

The third was his Report on Manufacturers, turned in on December 5, 1791.

For his two big financial innovations, Hamilton had a working model he could copy right in front of him — Great Britain.

The Dutch had been the first to stumble upon the secret for dealing with large debt. William of Orange had carried the recipe with him when he became King of England, Ireland, and Scotland in 1688.

The Bank of the United States, which opened its doors in Philadelphia in December, 1791, was Hamilton’s copy of the Bank of England, 1694.

‘National debt’ had once been synonymous with the monarch’s personal debt.

Its details were often a state secret.

The monarch, on a whim, might decide not to pay it. Or not pay one particular person he didn’t like.

The ingredients of the Dutch secret sauce were:

The national debt would no longer be the monarch’s secret. The title of Hamilton’s report is on the Public Credit. The debt would be ‘sold’ to well-off members of the public.

The government had to commit to religiously servicing the debt.

The target market had to be convinced of that. The root of the word ‘credit’ is ‘to believe’.

The debt instruments, the bonds, had to be transferrable and tradable in a public market. The price of the bonds would measure how much trust investors had in them.

There was, happily, a tonic — perhaps a better term is miracle cure — ready-to-hand for the anemic U.S. economy.

The vast ‘stock’ of old Revolutionary War debt was still around.

It was of uncertain and varying value. A few states had actually been conscientious about servicing their war debt.

Others had not.

Hamilton’s plan was for a debt restructuring, of the sort we now associate with a country like Argentina.

‘Assumption’ meant the new federal government would exchange all those miscellaneous old IOUs for new ones.

For simplicity, I’m going to call the new ones U.S. Treasury bonds.

Controversially, the old IOUs would be credited at original face value, not ‘discounted’.

It was an exchange of paper, new for old.

The hoped-for difference was that the new paper be good paper.

That was why Hamilton was so keen on a ‘just right’ tariff. The first tranche of the tariff revenue would be dedicated to paying interest on the debt.

The first stage of the miracle cure came from a ‘wealth effect’.

Holders of the previously near-worthless paper suddenly felt a lot richer after they exchanged it for the new.

That included those who had, over the previous years, picked the old stuff up on the cheap as a speculation.

Continental soldiers, for example, had been forced to take part of their pay in IOUs.

Those IOUs would be good — maybe — after the War. If the Americans won.

During the War, Hamilton’s friend William Duer had been a wheeler and dealer — a sort of scrounger — in provisions for the Continental Army.

Duer was the guy to whom a solider could take his IOU and sell it for a little bit of coin right now. At a deep discount, of course.

Many played the game. Abigail Adams took a flutter in the Continental paper. She instructed her business agent to pick some up on possibility it would become worth something someday.

In the day, ‘speculators’ were tutted about, but not stigmatized.

Before the eighteenth century, a ‘speculator’ was a spectator, as in sports. A speculator was a contemplative type, a ‘watcher’.

A speculator tried to buy low and sell high.

But then so did ordinary merchants.

In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith tried to work out a distinction:

The speculative merchant exercises no one regular, established, or well known branch of business. . . . He enters into every trade when he foresees that it is likely to be more than commonly profitable, and he quits it when he foresees that its profits are likely to return to the level of other trades.

But there was a more important stage in the miracle cure: the Treasury bonds would be a magic money multiplier.

Treasuries were the sort of ‘sound collateral’ bankers loved.

They would lend on them. That would put bank-created money in circulation.

It was indeed magical, almost alchemical. You could walk into a bank with the right piece of paper and walk out with a bag of gold or silver coins.

Estimates of the magnitude of the wealth effect are difficult to make, but have been attempted.

In 1913, Columbia historian Charles A. Beard outraged his contemporaries by suggesting the Founding Fathers had economic, as well as purely philosophical, motivations.

In his An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States, Beard estimated “at least $40 million gain came to the holders of securities through the adoption of the Constitution and the sound financial system which it made possible.”

For scale, $40 million was about 8 times the annual federal budget in 1792.

Land ‘speculation’, by the way, was practically a national pastime among the well-to-do.

Nearly all the founding fathers, including Hamilton, were involved in land ventures of some sort. George Washington, recall, was a surveyor.

Land — whether acquired by treaty, contract, or outright theft — was the backbone of the colonial experience.

And was one of the few things in which someone with some surplus funds could invest.

Doing so was vaguely patriotic. Buying tracts of undeveloped Western land showed confidence the new nation would grow.

Huge tracts of land, the so-called the western reserves, were the principal assets of the states and the new federal government.

Land is a great thing to own.

But it’s a notoriously illiquid asset.

Hamilton’s Treasury bonds, the ‘U.S. Sixes’ went on sale in October of 1790.

The entire issue sold out in a few weeks.

The Sixes, as the name suggests, paid 6% interest per year.

There were two others: the 3 percents, and the ‘deferred’.

But the Sixes were the most important.

The ‘deferred’ were the result of the new government’s cash flow problems. It would not have to start making interest payments on those for ten years.

Like British ‘consols’, the Sixes were perpetual bonds with no fixed term.

The concept of ‘perpetual’ bonds had made Congress uncomfortable.

It wanted the national debt to get paid off.

Eventually.

Just not now, as the prayer for chasteness goes.

Aside: the U.S. national debt would hit zero only once, during Andrew Jackson’s presidency, That came along with an unanticipated and nasty deflation.

So a ‘sinking fund’ was made part of the deal. It would allow the government, over time, buy its own bonds out of the market and retire them.

Hamilton would raid the ‘sinking fund’ far sooner than Congress had anticipated.

The bonds were purchased by a surprisingly broad public. A well-off tradesman might have picked up a few. The smallest denomination was $100.

Estimates vary, but a good guess is that perhaps 10,000 ‘economic entities’ (individuals, partnerships, corporations, municipal governments, trusteeships) soon owned the bonds.

Hamilton didn’t want the public to ‘buy and hold’ Treasury bonds.

Only.

The Dutch recipe required the bonds become actively traded in the secondary markets.

At the time, those were in New York, Philadelphia, and, to a lesser extent, Boston.

In New York, secondary market was in the Merchant's Coffee House.

Hamilton and his family lived nearby, in a small house at the corner of Wall and Water Streets.

In Philadelphia, the secondary market was in a coffee house on Chestnut Streets.

Communications were a little slow in those days. During one upcoming bout of market frenzy, there were as many as 40 stagecoaches a day racing between Philly and New York.

‘Outcry’ auctions of securities were held on a flat block out in front of the coffee houses, typically one at noon and another around 7 p.m. That same block might have been used a few hours earlier to auction slaves.

Auctions had been an interesting development from an information-theoretic point of view.

Some holders of the old Revolutionary War IOUs had no clue what they were ‘really’ worth. They might be tempted to take the first offer they got, such as one from Duer.

Auctions were perceived as more fair.

And, state and local governments liked securities auctions. They provided a convenient nexus at which financial transactions could be taxed.

In March 1789, recent bid/ask prices started to appear in print. Massachusetts Magazine started a regular column for those of Boston.

On May 17, 1792, twenty-four New York’s broker-dealers met under a buttonwood tree on Wall Street and signed an agreement to trade with each other on preferential terms. That was the origin of the ew York Stock Exchange.

The acid test for the new U.S. Treasuries would be how well they did in London and Amsterdam.

Aside: A few years on, with Britain back at war with (now) post-Revolutionary France, United States government debt would prove very popular indeed with European investors. It was a conveniently remote ‘safe haven’.

If Hamilton were a contemporary Wall Street guy who wants know a single market price when he walks into the office each morning, it would be that of his ‘U.S. Sixes’.

That market price of the Sixes were the metric for how much faith people had in the new U.S. government.

If the bonds were selling above ‘par’, 100, all was good.

If they dipped below ‘par’, that was not so good.

Hamilton took the price relative to 100 personally.

It was like the grade on his report card.

Dipping below ‘par’ was was just not a ‘D’ for Hamilton, it was something of an affront to the new nation. The Europeans might be laughing at us behind their lace-cuffed sleeves.

Hamilton would take steps to make sure below ‘par’ didn’t happen.

He invented the ‘Greenspan put’.

Which we’ll have to call the ‘Hamilton put’. Or name it after the central banker of your choice.

Starting in September 1790, one month after the ‘sinking fund’ law was passed, Hamilton started instructing William Seton, cashier of the Bank of New-York, to buy Treasuries out of the market a times when Hamilton feared they might fall below what he called their ‘proper’ or ‘due’ value.

It was a price floor.

Hamilton believed it his prerogative as Secretary of the Treasury, and quite possibly his duty, to prop up his bonds in the market when they needed it.

Hamilton’s ‘open market’ operations had nothing to do with retiring the bonds.

The ‘sinking fund’ was not yet in funds.

Hamilton’s Treasury had to take on new debt from the Dutch to make purchases of its own debt.

Hamilton’s two big financial plans had gotten through Congress only after some intense politicking.

Hamilton got one thing he wanted very much — for the new federal government to also ‘assume’ the leftover Revolutionary Wars debts of the individual states — only after a special side deal was negotiated with the South.

That resulted in Washington, D.C. being where it is today.

President Washington had been forced to get involved, in a slightly king-like manner.

Madison and Jefferson relied, unsuccessfully, on a Constitutional objection to slow down Hamilton’s big plans.

Hamilton’s second big financial innovation, the Bank of the United States, was another near-run thing.

Starting a National Bank was not among the powers explicitly granted to the new federal government by the Constitution.

If the Framers had wanted a big national bank, they would have said so.

Aside: It was a convenient time to be ‘originalist’. If you wanted to know what the Framers had intended, you could just ask them.

Benjamin Franklin, aware an objection like that might come up, for the longest time tried to get a power to ‘cut canals’ written into the Constitution.

Congress passed the bill authorizing the Bank’s creation on Feb 1, 1791.

But it looked like Washington intended ‘pocket veto’ it — not sign it within ten days.

Washington heard out Madison and Jefferson about it being unconstitutional.

That was also the opinion of the Attorney General, Edmund Randolph.

Washington asked Madison write down his objections. Madison assumed those might get incorporated in Washington’s veto message.

Hamilton, at the last minute, pulled an all-nighter. He wrote his former boss an lengthy, impassioned pleading on behalf of the bill.

Hamilton’s logic inverted that of Madison and Jefferson.

They argued that no power was available to Congress unless specified in the Constitution.

Hamilton argued that no power was not available to Congress unless so specified in the Constitution.

Washington was not fully convinced, but signed the Bank bill anyway.

For him, the simple way to resolve the deadlock was to accept the opinion of the cabinet officer in whose department the measure fell.

Which, of course, was Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury.

Madison and Jefferson lost that argument.

As we learned in civics class, the federal government has broad ‘implied powers’, and so on.

But focusing on the failed legal objection risks ignoring their other arguments.

A lot of Americans at the time didn’t much like banks, especially big banks.

Some still don’t.

John Adams groused in his old age in 1819: “Banks have done more injury to the religion, morality, tranquillity, prosperity and even wealth of the nation, than they can have done or ever will do good.”

The Puritan days were past, but America was still a religious nation. Usury, especially when it took advantage of the poor, was a sin.

For the more secular, even Aristotle had noticed there was something unnatural about interest, ‘money giving birth to money’. How did it do that?

Jefferson, a classicist and persistent debtor himself, called profits from purely financial speculation ‘barren’. It was morally inferior to investing to bring forth ‘real’ things.

Then there was the size of Hamilton’s national Bank of the United States. It was authorized to sell common stock to raise 10 million dollars.

Hamilton never thought small.

That was a staggering figure at the time. The combined capital of the five state banks then in existence totaled only $3 million.

In 1792, the total income of the federal government was $3.67 million, with outlays of $5.08 million.

Such a behemoth national bank might have monopoly power.

The state-chartered banks wouldn’t be able to compete. The big national bank would be able to set interest rates wherever it liked.

If it decided to set them high, farmers and trading merchants, who needed to take out loans routinely, might find themselves at the mercy.

On the other hand, the Bank might go in for easy money, and lend too freely to speculators and Wall Street types.

Which is what it did.

Aside: I can’t resist including a trick quote, written by Tobias Smollett in 1804, summarizing opposition to a national bank:

“The project was violently opposed by a strong party, who affirmed that it would become a monopoly, and engross the whole money of the kingdom: that as it must infallibly be subservient to government views, it might be employed to the worst purposes of arbitrary power: that, instead of assisting it would weaken commerce, by tempting people to withdraw their money from trade and employ it in stockjobbing: that it would produce a swarm of brokers and jobbers to prey upon their fellow creatures, encourage fraud and gaming and further corrupt the morals of the people.”

The trick: Smollett was actually writing about the Bank of England.

By late 1791, Hamilton’s monetary tonic was starting to work wonders.

After seven lean years, the animal spirits were back.

The stock market, such as it was, was on a tear. It was happy days for those on Wall Street who were bullish on America.

Aside: Merrill Lynch’s famous 1971 TV commercial was filmed in Mexico, to lower its cost.

All sorts of new ventures, such as toll-road and canal companies, were offering stock. There were as many new corporations formed in 7 months as there had been in the previous 7 years.

Especially new banks. Shares offered for the Rhode Island-chartered Providence Bank sold out in an hour, three times oversubscribed.

John Adams wrote: “The sudden accumulation of wealth in the hands of individuals has induced a mania.”

The word ‘mania’ became the root of the hashtags of the day. There was ‘bankomania’, and later ‘scrip mania’.

The new Bank of the United States, the product of Hamilton’s second plan, was responsible for the scrip mania.

On the English model, the ‘national’ bank would in fact be owned by private investors.

Eighty percent of it, anyway.

Wealthy investors would buy what was, legally speaking, common stock. The proceeds would give the Bank enough capital to get into business and start lending.

The other 20% would be owned by the government, which it paid for by transferring some of Hamilton’s Treasury bonds.

The initial offering of Bank of the United States stock took place on an auspicious date, July 4, 1791, in Philadelphia.

It was heavily oversubscribed.

Among the stock-buying public, however, cash was still tight.

So ‘subscriptions’ to the stock were sold on an installment plan. The down payment on one share was $25.

That had to be paid in hard ‘specie’, gold or silver coin.

The down payment bought a ‘scrip’, a right to own a share after making the scheduled payments over the next two years. The final share price would total $400.

Scrips were tradable.

Which essentially made them futures options.

They offered great leverage. As long as they were going up.

A scrip that required only the $25 down could be sold for $300 a few months later.

Hamilton was endlessly inventing creative uses for precious Treasury bonds.

The more action in the bonds, the better. That kept the market liquid.

And — probably — helped keep their price up.

For large transactions, the bonds themselves could function as paper currency. They could be signed over.

Hamilton made sure that private investors in the Bank could make their subscription payments, if they liked, using Treasury bonds.

That would take those Treasuries out of the public market. The reduction in supply would help keep the price up.

The dates on which everybody’s Bank subscription payments were due were public knowledge.

A few clever Wall Street types figured that would induce predictable price jags they could time and trade.

Bank scrip became the tail wagging the Treasury bond dog.

The various ‘manias’ soon became more general.

Men and women “of all sorts and conditions” got into the market, from “the small merchant tempted out of his line and the even smaller clerk or artisan who dreamed golden dreams of getting rich quick.”

The nearest thing to it in the history books was England’s South Sea Bubble, and that had been a long time ago, 1720.

Some observers tutted and clucked.

Jefferson worried the all that action in the stock market was seducing his yeomen farmers. They had lost in their cows: “his cattle & crops are no more thought of than if they did not feed us. Scrip & stock are food and raiment here.“

The curmudgeonly John Adams looked forward to enjoying a bit of schadenfreude. The mania will “be cured by a few bankruptcies which may daily be expected, I had almost said, desired.”

Jefferson groused that “the fate of the nation seem to hang on the desperate throws & plunges of gambling scoundrels.”

As the bubble expanded, so did populist opposition to Hamilton’s big financial plans.

The window of bipartisan good feeling that had been open during the ‘100 days’ had definitely slammed shut.

The populist opposition would take a little time to coalesce.

When it did, the deepness of the divide would create the first two political parties. Political parties were something the Founders hadn’t anticipated, nor had they wanted.

The populists of the day may or may not have understood the fine points of Hamilton’s financial plans.

But they (correctly) suspected Hamilton’s plans probably favored his class, the financial and mercantile elite, over them.

The odds of Hamilton getting another one of his big plans through Congress were growing small.

As it so often does in the United States, military considerations had prompted Congress to consider compromising its laissez-faire inclinations.

On January 8, 1790, in his first message to Congress, Washington asked it to come up with a plan “for the encouragement and promotion of such manufactories as will tend to render the United States independent of other nations for essential, especially military supplies.”

The House passed that chalice on to Hamilton.

Hamilton submitted his third report, The Report on Manufacturers, in December 1791.

Unlike his first two plans, Congress filed it away.

I don’t think Hamilton cared.

He no longer needed Congress. Or so he was convinced.

And I’m sure he was tired of arguing with them.

Hamilton could kick off U.S. manufacturing on his own.

Just Do It.

Show, not tell.

Its was a very ‘hands-on’ approach to a research report.

It would get him mixed up in industrial piracy, patent infringement, talent poaching and a venture-capital-style start-up of a ‘National Manufactory’.

All while serving as Secretary of the Treasury.

Hamilton had a secret weapon: his beloved U.S. Treasury bonds.

Aside: There are a few tantalizing paragraphs in Hamilton’s Report in which he suggests a 'Board' — independent of Congress — should be in charge of promoting "the arts, agriculture, manufacturing and commerce." In an alternative history, we can fantasize Hamilton’s ‘Board’ evolving into something akin to Japan's MITI, its Ministry of International Trade and Industry.

Charity was oddly intwined with early manufacturing in the colonial America.

The ‘Societies’ of the day have no exact modern equivalent.

Many were voluntary civic associations founded to promote some publicly virtuous thing.

Others were that, but more closely resembled modern-day corporations. They sold stock — ‘subscriptions’ — and went into business.

Not necessarily with a burning profit motive, but to help them do the publicly virtuous thing.

Benjamin Franklin’s pre-War ‘Philadelphia Silk Society’ is an good example.

Franklin talked civic-minded Philadelphians into subscribing as a way of assisting the city’s poor.

The Society set up what’s called a ‘filature’ for unspooling thread from silkworm cocoons. It hired women spinners “chiefly of the poorer sort.”

Hamilton had taken a bit of a flyer in textiles in 1789, not many months before becoming Treasury Secretary.

Hamilton the lawyer had organized, and taken some founders’ stock in, the ‘New-York Manufacturing Society’.

The New-York Society, on the earnest Philadelphia model, was formed “for the purpose of establishing useful manufactures in the city of New-York, and furnishing employment for the honest industrious poor.”

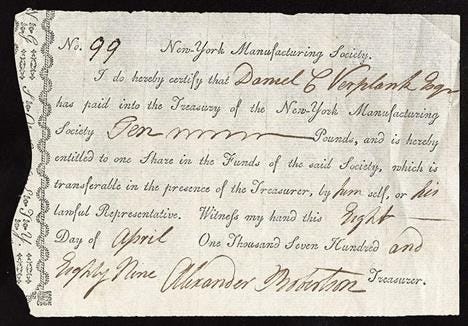

It had 246 subscribers who paid £10 — in ‘New York state currency’ — for each share. A share receipt signed by Hamilton:

The Society constructed a large brick building on Vesey Street. It bought “reels, looms, carding machines, spinning jennies, with every other machinery necessary and compleat for carrying on the cotton and linen manufacture.”

Another idea was to weave cloth out of wool. Merino sheep were a big at the time.

The looms were supposed to be run by a waterwheel in one of the small streams that (then) ran aboveground in lower Manhattan.

The stream proved unreliable. It ran dry in the summer. Anyway, it didn’t have much oomph.

The stream was replaced by a more dependable ox, who walked in a circle.

Women were involved in a different impetus for America doing its own manufacturing. That one was an anti-British negotiating tactic during the run-up to 1776.

The American colonials, mostly in Boston, adopted ‘nonimportation’ as a strategy to get the British to back down on things like the Stamp Tax.

‘Nonimportation’ didn’t make much of an impression on the British.

But it did result in an endearing fashion fad for ‘homespun’, the rough, scratchy fabric made by colonial women at home. Wearing homespun was virtue-signaling in extremis.

Homespun managed to resonate with both latent Puritanism and mercantile economic theory.

Wearing expensive imported fabrics, especially silks — even black silk for mourning — was a sinful luxury. And the ‘specie’ spent to buy them exited the country.

For Jefferson, European-style factory manufacturing was not only unnecessary in the new republic, it was undesirable.

Some small-scale artisanal manufacturing, of course, was need in support of Jefferson’s beloved agriculture. Otherwise, factories had no place in his New World:

Carpenters, masons, smiths, are wanting in husbandry: but, for the general operations of manufacture, let our work-shops remain in Europe.

Aside: that quote dates from 1785. Later, after some manufacturing had gotten established in the U.S,. Jefferson would moderate that view, saying we could have both.

The workshops of Europe were not quite yet Blakes’s ‘Satanic Mills’.

That would come a few years later, when they started burning coal.

But factories already had a bad reputation.

For English workers of the time, the large textile mills were cut from the same cloth as prisons and workhouses.

In Europe, what with its ‘surplus population’ — to quote Ebenezer Scrooge — prisons, workhouses and factories might be necessary for social control.

The urban poor were an unruly and potentially revolutionary lot. They would prove that in France a few years on.

A widely-held economic theory of the time was that factory manufacturing had a natural, Malthusian-like tendency to reduce workers’ wages to subsistence level. That ‘law’ would later be formalized by David Ricardo and picked up by Karl Marx.

The young United States had the opposite problem. It was relatively underpopulated. Its labor was more expensive than Europe’s.

A writer at the time: “manufactures can only be carried on to advantage in states full of people, and whose labour is low.”

Working a farm that you owned was widely perceived as infinitely preferable to working for a wage in a factory: "So much more agreeable is that profession!"

Factory workers, even skilled ones, would find cheap western land a fatal attraction. They’d be off for the frontier just as soon as they saved up a down payment.

That actually happened. A postmortem of a failed New York factory venture circa 1795 listed one of the problems as:

The English workmen are dissatisfied, and ready to leave the factory as soon as they have saved up a few pounds, in order to become landholders up the country, and arrive at independence.

The Report on Manufacturers, as it was submitted, is bit of a disjointed document.

There’s a ‘theory’ section, clearly written by Hamilton.

The rest is a business plan.

That part was drafted by Tench Coxe, Hamilton’s Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, and worked over by Hamilton, so consider it co-written.

More about Coxe in a minute.

First, some terms of the day require translation.

‘Bounties’ were one idea for encouraging ‘manufacturers’.

Bounties were mostly like prizes, but a bit like subsidies.

For example, in 1784 the Connecticut assembly, to encourage a silk industry, offered any farmer who planted 100 mulberry saplings a ‘bounty’ of 10 shillings a year for 3 years. Connecticut also guaranteed a price of 3 shillings an ounce for raw silk.

In the theory section, Hamilton, ever the even-handed lawyer, first gives time to the opposing views.

In The Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith had openly stated that the American Colonies should not attempt manufacturing:

Were the Americans … to stop the importation of European manufactures, and, by thus giving a monopoly to such of their own countrymen as could manufacture the like goods, divert any considerable part of their capital into this employment, they would retard instead of accelerating the further increase in the value of their annual produce, and would obstruct instead of promoting the progress of their country towards real wealth and greatness.

Hamilton’s own restatement of the argument against government trying to promote manufacturing — call it the laissez-faire position — is actually rather eloquent:

To endeavor, by the extraordinary patronage of Government, to accelerate the growth of manufactures, is, in fact, to endeavor, by force and art, to transfer the natural current of industry from a more, to a less beneficial channel. Whatever has such a tendency must necessarily be unwise. Indeed it can hardly ever be wise in a government, to attempt to give a direction to the industry of its citizens. … To leave industry to itself, therefore, is, in almost every case, the soundest as well as the simplest policy.

Aside: A few decades on, Frederick List, the hugely influential 19th century German economist (who had studied Hamilton’s Report closely), would mock British economists like Smith who preached the gospel of free trade to developing nations.

They were hypocrites: Do as we (now) say, not what we (once) did. In List’s evocative phrase, what they were trying to do was ‘kick away the ladder’. Britain, having climbed up the ladder of economic development, had no interest other nations following it. They might become its competition.

Hamilton spent much of the theory section of his Report trying to come up with answers for the high cost of labor in the United States.

One answer, then as now, was automation: labor-saving machinery.

Another answer, then as now, was immigration. For Hamilton, immigrants were preferably skilled and English, or at least white European. At the time, even the Irish need not apply.

Another solution was to copy a recent British innovation. The textile mills could be filled with children.

For Hamilton, what trumped all other arguments was Great Power competition.

Hamilton, the realistic lawyer, simply looked at what other countries were doing: “the bounties premiums and other artificial encouragements, with which foreign nations second the exertions of their own Citizens.”

The young United States, if it wanted to match those foreign nations in power and prestige, had no choice but to adopt similar measures.

However unpalatable those might be to believers in laissez-faire.

Hamilton was an early practitioner of Realpolitik.

But what sort of ‘artificial encouragements’?

Madison, in 1789, doubted politicians had the requisite knowledge to ‘pick winners’:

it is also a truth, that if industry and labor are left to take their own course, they will generally be directed to those objects which are the most productive, and this in a more certain and direct manner than the wisdom of the most enlightened legislature could point out.

Aside: Ninety years before Friedrich Hayek was born. A condensed version of Hayek’s ‘knowledge problem’: knowledge is dispersed across individuals. No single authority can possess or process all of the information necessary to manage a complex system.

States wanting to hand out prizes was not terribly controversial.

But it would be another thing if legislatures got into the habit of handing out money to private interests. That was a recipe for the corruption of political ‘virtue’.

Jefferson, in his private notes on Hamilton’s Report, opined:

Bounties have in some instances been a successful instrument for the introdn. of new and useful manufactures. But the use of them has been found almost inseparable from abuse.

Aside: In the last half of the 19th century, the land-grant subsidies for railroad building proved poisonously corruptive to the body politic. The corporations formed to take them were dependably looted by their private owners, who then devoted a portion of their gain to purchasing politicians. That keeping the subsidy cycle going. Competition among the railroads was not only about laying down miles of track.

If a ‘society’ had a sufficiently appealing public purpose and the right political connection, it could hope to get a charter from a state government. That would make it legally what we now call a corporation.

Getting a charter then required a state legislature to pass a law and have it signed by the governor.

Those laws often granted special benefits. The states had a pretty common menu.

The society’s land and buildings might be exempted from property tax. Its workers could be exempted from the poll tax. Or from having to serve in the state militia.

Other benefits were more in the realm of zoning, eminent domain, canal privileges, and water rights.

An unusual one was that a state could give a society the right to run lotteries, keeping the proceeds after prizes.

Federal charters were rare, and controversial.

Hamilton’s Bank of the United States, of course, had one.

The House of Representative, in its 1790 charge to Hamilton, had asked him to make a survey U.S. manufacturing as it then stood.

There wasn’t much.

In 1794, diplomat Charles Maurice de Talleyrand was hiding out in America.

Talleyrand was then on the lamb from both the British and his fellow French Revolutionaries. His diplomatic passport had been signed by Danton, and presumably expired with Danton’s famous death.

Talleyrand sniffed that America:

is but in her infancy with regard to manufactures: a few iron works, several glass houses, some tan yards, a considerable number of trifling and imperfect manufactories of kerseymere and, in some places, of cotton…

Hamilton sent around a circular letter asking anyone who knew about manufacturing to write back.

He collected samples from textile mills. Later, Hamilton would lay them out for members of the House to inspect, as if at a trade fair.

Hamilton got one very detailed response from Tench Coxe in Philadelphia.

Coxe was from an old and well-connected landowning family. His great-grandfather had been court physician to Charles II and had been ‘favored’ in the early Colonial land grants. His descendants at various times owned most of New Jersey and ‘The Carolana’.

Aside: Daniel Coxe III, Fellow of the Royal Society, famously poisoned a cat with tobacco in a lecture-demonstration described by Samuel Pepys in his diary entry for 3 May 1665.

Tench Coxe’s politics during the Revolution were a bit confused. Some thought he was pro-British, a Tory.

But after the War he was a very public advocate of U.S. textile manufacturing.

Coxe headed up something called the Manufacturing Society of Philadelphia.

Tench Coxe had published various ‘visionary’ articles about the future of U.S. manufacturing in the Philadelphia papers. He included his newspaper clippings in his letter to Hamilton.

Tench Coxe had been involved in a flyer in textiles before.

The ‘Pennsylvania Society for the Encouragement of Manufactures’ opened a small factory in 1787.

In best Philadelphia tradition, one of its goals was to provide jobs for the unemployed.

During the winter of 1787 and spring of 1788, it gave work to perhaps two hundred women who spun linen into yarn.

It also conducted one successful and ultimately very consequential experiment: it was able to spin short-staple American-grown cotton into usable thread.

After improved cotton gins came into use after 1793 — Eli Whitney gets a little too much credit as the ‘inventor’ — slave-picked King Cotton would come to dominate Southern agriculture. And British textile manufacturing.

Which would tee up the Civil War.

Two years later, the both the New-York and Philadelphia societies would fade and fail..

Textiles were a tough business to break into.

They’re not exactly high margin.

And cheap British imports were keeping prices down. A writer summed up what caused the Philadelphia society too fail with a single word: ‘Manchester’.

The early manufacturers would not get the high protective tariffs they wanted for their ‘infant’ industry until 1816.

Capital was needed for buildings and machines. But if a ‘society’ had to take out loans, the interest payments could become killer.

In March 26, 1789, the Pennsylvania state legislature tried to help.

It bought 100 shares in the Philadelphia Society, saying "the sums subscribed [by private investors are] inadequate to the prosecution of the plan upon that extensive and liberal scale, which it is the interest of this state to promote."

None of those of measures helped.

At least not enough.

“A Citizen of Boston” wrote on January 18, 1792:

I am sorry to say, that very few enterprizes in the manufacturing line, in this town have ever been fraught with other consequences than those of disappointment, and absolute loss.

Hamilton’s first Assistant Secretary of the Treasury had been William Duer.

In March of 1789, Duer resigned his job at the Treasury to pursue, as his statement would say today, ‘other interests’.

Duer’s ‘other interests’ were speculation, land and financial.

Duer is a fascinating character.

He’s routinely referred to now as “America’s First Wall Street Villain”, a sort of early days Bernie Madoff.

I rather like him.

Duer was one of Hamilton’s many ‘friends’ from Revolutionary War days.

He was a close one. Their wives were cousins.

Duer was rich, successful, and popular among his large acquaintance.

When Duer married Kitty Alexander, daughter of a wealthy trader and veteran of the French and Indian War, George Washington gave away the bride.

Duer arranged for George and Martha to live in a friend’s ‘mansion’ at 39 Broadway during the short time the government was in New York in 1790.

Duer and his wife lived well. They ‘cut a figure’ in New York society.

Which made him a natural target for envy. And, later, hate.

But a testimonial — admittedly from someone who had just concluded doing some bit of business with Duer — is worth recording:

He is a gentleman of the most sprightly abilities, and has a soul filled with the warmest benevolence and generosity. He is made both for business and the enjoyment of life, his attachments strong and sincere, and diffuses happiness among his friends, while he enjoys a full share of it himself.

Aside from being his friend and cousin by marriage, Duer was also Hamilton’s predecessor in office.

Duer had been the Secretary of the Continental Congress’s three-man Board of Treasury.

Duer sold supplies to the War Department, and before that to the Continental Army. He sold the infant U.S. Navy the timber masts used for its new ships, for example.

General Henry Knox, Washington’s Secretary of War, who approved Duer’s contracts, was also Duer’s partner in some land deals in Maine and Ohio.

Like I said, conflict of interest wasn’t much of a thing back then.

During the War, Duer had developed a prudent habit. He rarely put any of his deals down in writing.

He was apparently a whiz at keeping numbers in his head and doing mental arithmetic.

Another Duer habit was to made sure he got a ‘taste’ in any deal. Call it his commission, if that makes you feel better.

Duer’s job put him in the unique position to accumulate a collection of the miscellaneous state and continental warrants, ‘specie certificates’ and the like, with which payments for public supplies were made.

When those were exchanged at face value for U.S. Treasury bonds, Duer did very well indeed. When people complained about ‘speculators’ benefiting from federal assumption of the debt, it was Duer they had in mind.

In the bull market of 1791, Duer was a bull’s bull.

Duer was not on TikTok, but he was an ‘influencer’. Where he led, others followed.

Duer’s thinking was the subject of a great deal of public speculation then, and still is.

Duer was famously ‘long’ on Hamilton’s U.S. Treasury bonds.

He had worked at the Treasury with Hamilton. So he may have had a sincerely high opinion of them.

Duer was certainly aware of the ‘Hamilton Put’. His downside risk was limited.

Should the bonds he held sink too far, Hamilton’s Treasury could be counted on to buy them off him.

Duer bought all the Treasuries he could afford, then borrowed to buy more.

That’s not the worse trade — a ‘carry’ — if you can borrow cheap. The Bank of New-York was lending at 5%. The bonds paid 6%. Duer could pocket the 1% difference.

Outsiders fumed about what looked to them like insider trading going on in Hamilton’s Treasury Department.

Conspiracy theories were as popular then as today. There were many about Duer. One was that Duer planned to buy up all the Treasury bonds, then ‘squeeze’ the market.

The problem wasn’t that Duer was a bull.

The problem was that Duer was a highly leveraged bull.

Hamilton replaced Duer by hiring Tench Coxe.

They became business partners, of a sort.

Coxe had given Hamilton a list of things he thought were holding back manufacturing in the United States.

There were two bigs ‘lacks’: lack of capital and lack of knowledge.

Hamilton, the financial engineer, had a brilliant solution for the lack of capital.

The plan outlined in the Report on Manufacturers was in motion by mid-1791.

As business plans go, it outlined an odd sequence of events.

The first thing they would do is raise a whole lot of money.

Aside: In some ways, more akin to a starting venture capital fund than a venture capital venture.

The name of the new venture would be the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures, usually shortened to S.U.M.

Wealthy people, nearly all from Philadelphia or New York, would ‘subscribe’ — pledge to buy — stock in S.U.M.

Hamilton uses a charming word for them — the ‘adventurers’.

Hamilton again wanted to go big.

The authorized capital of the National Manufactory would be $1 million.

Aside: Coxe’s original plan called for $500,000. Hamilton apparently doubled it.

That number was intended to raise eyebrows, and it did.

The largest canal-construction company of the day was authorized to raise only $400,000 in capital. And it had not been able to raise that much.

Word about Hamilton’s new venture got out in August, 1791.

What with Hamilton’s network of contacts, his good name, and the vague impression that S.U.M. was blessed by the government, the initial subscriptions sold themselves.

A lot got pledged quickly. Not all of that, of course, was collected in cash.

When the scrip-holders — stockholders to be — were known, they got together and elected a board of directors. That happened on November 25, 1791, in Philadelphia.

To be clear, Hamilton himself never was a stockholder. He clearly felt that would have been inappropriate while he was Secretary of the Treasury. Hamilton was elected to S.U.M.’s board of directors after he left office in 1795. It’s unclear if he ever attended a meeting.

Hamilton’s intimate friend William Duer was the obvious choice to be ‘Governor’ of S.U.M.

The ‘Governor’ was not the CEO, but the chairman of the board.

The money guys assumed they would hire a “Superintendant-General of the Works of the Society” — on salary, no equity — to run things.

He’d have to live at the site, so maybe they’d build him a house.

To modern eyes, a missing figure in the business plan is a driven entrepreneur: one person who had a basic grounding in the technology; could exert a reasonable amount of control; and had some financial skin in the game.

The first candidate for Superintendant-General was Nehemiah Hubbard of Middletown, Conn. He was offered $2,000 per annum, about $68,000 today.

Hubbard turned it down.

Hubbard had been deputy-quartermaster-general for Connecticut during the war, and in 1792 was engaged in foreign trade.

Hubbard didn’t think he was qualified for the job. The risks involved in being a trading merchant, he understood. This manufacturing thing was too new for him.

So in early days Duer and Hamilton, plus the board, were what S.U.M. had by way of management.

Both Duer and Hamilton were, of course, busy guys.

Hamilton had the Treasury to run. Duer had his ‘other interests’.

In January 1792, Duer’s ‘other interests’ started to heat up.

Aside: Hamilton did apply his famous self-study skills to trying to master the complicated mechanical workings of the looms and similar devices of the day. Some pages in his papers display some very nerdy fascination with them.

It took some time to decide where, exactly, the ‘National Manufactory’ should be located.

New Jersey had the inside track. Coxe’s family still owned parts of it. And it was halfway between New York and Philadelphia, where the ‘adventurers’ lived.

Hamilton negotiated a corporate charter for S.U.M. with the governor of New Jersey, William Paterson in November 1791.

Aside: Present-day Paterson is called that for a reason.

The state charter authorized a ‘district’ — somewhere in New Jersey — “not exceeding in contents, the number of acres contained in six miles square for the purpose of establishing within the same, the principle seat of the Society for useful Manufactures.”

Duer, no stranger to hype, tried to get parts of state competing against each other for the honor of hosting S.U.M.

On Dec. 12, 1791, Duer put an ad in the New Jersey papers touting (his caps): “The advantages to be held up to the Society for employing within the proposed district, an active capital of ONE MILLION OF DOLLARS.”

Friendly boosters in the press pontificated that the winning location would become the future manufacturing capital of U.S.

It would be as important as the new political capital then being laid out on the Potomac.

The site needed a waterfall. They sent people out to look for one.

An excellent one was found on the Passaic River.

But S.U.M.’s board of directors were slow to make up their minds and act.

As a footnote on how common land speculation was, a S.U.M. board member advised, after the site had been favorably mentioned in a board meeting: “I am of opinion it will be prudent to purchase the Lands at the falls of the Pesaick & in the vicinity of them without further delay […] to prevent Speculations, which you may depend upon it will be made, if we neglect to buy at the present moment.”

S.U.M. eventually purchased 700 acres of land above and below the Great Falls.

New Jersey subscribed to $10,000 in S.U.M. stock.

In exchange for that, the state got a right — if it felt it needed — to appoint an auditor to go over the books.

Spoiler: In 1804, a Col. John Dodd, council member from Essex County, was one such appointee. He admitted he couldn’t get to the bottom of S.U.M.’s accounts, but reckoned it had spent all but $20,000 of its original capital “in erecting the works and in fruitless attempts to carry them on.”

The land ultimately proved to be S.U.M.’s best asset. New Jersey eventually traded its shares for a few tracts, valued in 1816 at $11,000. In 1852, it sold them for $30,000.

Hamilton negotiated a long list miscellaneous benefits from New Jersey, although no outright ‘bounties’ or subsidies.

Aside: In retrospect, those were probably what the ‘National Manufactory’ really needed.

Hamilton knew start-ups could have cash-flow problems in early days. He negotiated a right for S.U.M. to hold lotteries in New Jersey and keep the proceeds after prizes.

Aside: Hamilton’s papers include several fascinating pages on which he worked out, in great detail, various numeric schemes for lottery prizes.

S.U.M. would have land-use authority inside its capacious industrial zone. It would do the layout the future town.

S.U.M. was thinking big. Plots to accommodate up to 40 future mills were laid out.

In 1816, at the short-lived, post–War of 1812 manufacturing peak, there would be 16 mills in operation (but not by S.U.M.) along the Passaic. S.U.M.’s allocated land slots would be full up by the 1850s.

S.U.M. got water rights for much of northern New Jersey above the falls.

That concession later proved quite valuable. It also led to a decades-long ‘water war’ after northern New Jersey started to develop.

The land and mill buildings would be exempt from property tax. The property tax exemption was in perpetuity.

That blessing also carried a bit of a curse. It was too good to give up. It inhibited S.U.M. from selling its land, and trapped it into becoming a landlord.

As a factoid of U.S. legal history, the corporate charter negotiated by Hamilton for S.U.M. in 1791 is probably the longest-lived.

In 1945 the charter and property were acquired by the city of Paterson, finally snuffing out S.U.M.’s legal existence.

By New Year’s Day of 1792, the business plan seemed to be moving along.

Subscribers had been found to take shares.

The advantageous charter had been obtained from New Jersey.

The site on the Passaic had been settled upon.

The year 1792 would require engineering of a non-financial kind.

Buildings had to be put up, most importantly the future cotton mill. Raceways had to be dug to bring water from above the falls to the mill sites.

And the ‘labor-saving machines’ had to be acquired.

Coxe’s second ‘lack’ holding back manufacturing in the young United States was lack of knowledge.

Americans just didn’t know how to do it.

And the British had draconian laws designed to keep it that way.

Artisans who had worked in the U.K. textile industry were prohibited from leaving the country.

On a few occasions, departing ships were boarded at sea. Papers were checked.

If appended, an emigrating artisan could be charged with treason. The penalty was forfeiture of property and citizenship.

Anyone caught trying to smuggle out a textile machine out of the UK got off a little lighter — only 12 months in prison and a heavy fine.

Hamilton and Coxe were both obsessed with getting their hands on the latest and greatest.

They paid ‘bounties’ to recent immigrants who knew the secrets.

Hamilton wrote of one: “[he] pretends to a knowledge of the fabrication of most of the most valuable Machines now in use in the Cotton Manufactory.”

‘Pretends’ is an operative word. The artisan-emigres were selling themselves. They tended to be a boastful bunch. A few were just over from Belfast. The American buyers could never be sure they weren’t falling for a load of blarney.

Coxe especially wanted to get his hands on an ‘Arkwright machine’.

In 1768, Richard Arkwright of Bolton, Lancashire hired a clockmaker, John Kay, to devise a new machine for spinning long-staple cotton into thread.

Aside: Lancashire was where technology action was at the 1760s, the Silicon Valley of its day.

Arkwright got a British patent on the machine the next year. He became notorious for enforced his patent with extraordinarily zeal.

One of beauties of the Arkwright machine was that it could be operated by unskilled workers.

Arkwright set up factories and filled them with children. And a few women.

The children worked 13 hour shifts. The factories ran 24/7. “The mills never leave off working,” a visitor to the area wrote.

Arkwright, to his credit, did refuse to hire children under seven.

Another Arkwright innovation was to install indoor toilets in his second factory.

That was so his workers wouldn’t have to spend so much time off shop floor hiking out into the woods.

For Hamilton and Coxe, luring over British artisans was a patriotic act.

In January 1790, Coxe went into a 50-50 partnership with George Parkinson, a recent English émigré who “possessed ... the Knowledge of all the Secret Movements used in Sir Richard Arkwright’s Patent Machine.”

William Pearce arrived in New York from Belfast in July 1791 carrying various wooden models of textile machines.

He also carried glowing letters of introduction to President Washington, to Hamilton, and various other American worthies.

Those were written by Thomas Digges, a well-off Virginia landlord who knew Washington. Digges had crossed the Atlantic “in order to get over some Tenantry, and among them Artists [artisans].”

For Pearce, the most important letter of introduction he carried was to William Seton, cashier of Hamilton’s Bank of New-York.

Digges had promised Pearce that his passage money, and eventually that of his family, would be reimbursed. It was.

Digges’s activities as a talent scout soon came to the attention of British authorities. They impressed upon him the wisdom of getting out of the country.

President Washington later praised Digges for “his activity and zeal (with considerable risk) in sending artisans and machines of public utility to this country.”

Once Pearce got to Philadelphia, Hamilton fronted him $100 in cash (about $3,500 today) so he could get to work trying to make actual working machines based on his models.

The most infamous artisan-emigrant was Samuel Slater, later reviled in England as ‘Slater the Traitor’.

Slater had gone to work at age ten in Arkwright’s first water-power cotton mill in Cromford, Derbyshire.

His family indentured him as an apprentice after his father died.

Slater, done with his apprenticeship at age 21, saw an ad placed in a British newspaper by Coxe’s Philadelphia Society. It offered a £100 reward to anyone able to build textile machines in the United States.

British passport control fell for Slater’s story that he was an farmhand.

After Slater arrived in New York in 1789, he worked a few months at Hamilton’s own New-York Manufacturing Society.

There he presumably heard about the problems of William Almy and Moses Brown in Rhode Island.

Messrs. Almy and Brown had been able get their hands on a spinning frame 'on the Arkwright pattern'.

But they’d been unable to figure out how to make the thing to work.

Slater, working from memory, got it going for them.

Two decades later, Slater had his own chain of mills.

Arkwright lost the British patent on his machine in 1785, when Kay’s story came out.

So American attempts to copy it no longer infringed it.