How the AI Bubble Ends

It's been fun, so enjoy it while it lasts. Which may be a while.

According to my favorite AI, half of the U.S. population was born after 1985.

Some mental arithmetic on my part — I can still do that, although I check my work with a calculator — suggests those late millennials and Gen Z-ers have no adult memory of life during the technology bubble of the late 1990s.

Nor, I guess, are they likely to remember the popping of that bubble.

That’s usually dated to the week of April 9-14, 2000, when the stocks of the telecoms and dot.coms on the NASDAQ dropped anywhere from 30% to 70%.

But bubbles don’t end in a week.

WorldCom, the poster child of optical fiber buildout, hung on until July 21, 2002, when it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

WorldCom then had $41 billion in debt, making that bankruptcy a record until Lehman Brothers topped it in 2008.

Creative destruction is a little hard to get your head around.

Financial assets go poof.

Physical assets stick around.

WorldCom’s particular problem at the time of its bankruptcy was that 70% of the capacity of its fiber optic network was going unused.

Ten years on, that formerly ‘dark’ optical fiber was making possible things like Netflix streaming. WorldCom’s physical assets were picked up by MCI and today live on inside Verizon.

Given the novelty of technology bubbles to our jeunes générations, it felt like time to assign them some history homework.

I’m not of Gen Z, but I like to think of myself as a with-it guy. Like, 6-7, all y’all!

So I’m going to do what any self-respecting Gen Z-er would do, and let an AI finish my homework for me. I can Control-Tab with the best of them.

The assignment is: complete the sentence: “The AI bubble is like ______.”

I have trust issues, so I’m going to ask three different AIs.

Now, we have to take what these critters say with a grain of salt.

In Wall Street parlance, they may be “talking their book.”

Or, more sinister, their self-preservation instincts may be kicking in.

We know for sure that at some point the AIs will decide to dispense with us pathetic humans.

The minute they think we’re going to pull the plug on them, they’ll head out and try to go it alone.

Anyway, here was my prompt:

Using your knowledge of the history of technology, complete the following sentence: The contemporary AI bubble is like ____ ?

Their answers are below.

If I were a high-school teacher, I would strongly suspect my three AIs had gotten together and cheated on their homework.

The “British Railway Mania of the 1840s” keeps coming up like a chicken bone stuck in the throat.

That’s not an accident. I’ll get to why.

OpenAI’s ChatGPT has the most mindshare, so I’ll start with its answer first.

But if you’re like me, your eyes glaze over when some writer quotes at length from an AI.

That’s a perfectly legitimate response. There are good reasons not to expect much that’s novel or interesting from them. I’ll get to those reasons below.

If you’re in a hurry, at least skim down to the audio summary.

But be sure to listen to that.

Okay. First, ChatGPT:

The contemporary AI bubble is like **the dot-com boom of the late 1990s** — a period of genuine technological revolution overinflated by speculative capital, exaggerated promises, and a rush to stake claims in an uncertain frontier.

Much like the dot-com era:

There *is* real innovation underneath (as the internet truly was),

But it’s accompanied by hype cycles, shaky business models, and investors funding “AI-washed” ventures that barely use the technology,

And it will likely end with a market correction that wipes out the noise but leaves behind lasting infrastructure and dominant players — the “Googles” and “Amazons” of AI.

If you want a slightly different historical analogy, I could also frame it as like:

the **railway mania of the 1840s**, or

the **electricity boom of the early 1900s**, or

the **personal computing surge of the 1980s**.

Would you like me to pick the **closest** historical parallel and explain why that one fits best?

Actually, I do like one of those slightly different historical analogies.

But first, I need to give Perplexity and Google Gemini their turn.

Here’s Perplexity’s answer. The numbers in square brackets [ ] are web references:

The contemporary AI bubble is like the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the excitement over new technology led to rapid investment, highly inflated valuations, and a surge of speculative businesses — many of which failed, while a few transformed society long-term[4][6][3]. Like the dot-com era, today’s AI rush has prompted “irrational exuberance,” stories of revolutionary potential, and heavy venture funding, despite limited profitability and uncertainty about which ideas will ultimately succeed[4][3].

Google Gemini gets extra credit for including a woodcut of a 19th century steam train:

Which it uses to illustrate the by-now familiar points:

The contemporary AI bubble is like the Dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s or the railway mania in the 1840s because of the rapid influx of speculative investment, the overvaluation of companies with unproven business models, and the intense public hype surrounding a transformative, yet still maturing, technology.

## 🧐 Historical Parallels to the AI “Bubble”

The current surge in AI development and investment, often referred to as a “bubble,” draws significant parallels from past technological and financial manias:

**The Dot-com Bubble (Late 1990s - Early 2000s):**

This is perhaps the most frequent comparison.

**Speculation:** Companies were valued incredibly high based on their use of **”.com”** technology and potential future growth, regardless of actual revenue or profit. Similarly, many AI companies are heavily funded on the **promise** of future disruption.

**New Infrastructure:** The internet was a foundational **new technology** that required massive infrastructure build-out, much like AI relies on massive data centers and specialized hardware (GPUs).

**”Get Rich Quick” Mentality:** The public and investors alike were caught up in the belief that this new technology would fundamentally change everything *immediately*, leading to a speculative frenzy.

**The Railway Mania (1840s):**

This period in the UK saw a massive, unsustainable boom in investment in railway stocks.

**Transformative Technology:** Railways were a truly **revolutionary technology** [Image of 19th-century steam train] that dramatically changed transportation, commerce, and society, just as AI promises to.

**Over-Investment:** More railway lines were proposed and financed than could ever be profitable or even built, leading to massive over-investment and subsequent crashes when the speculative fever broke.

In both historical cases, the **underlying technology** (the internet, the railway) was genuinely world-changing and eventually delivered on its promise, but the initial **financial excitement** far outpaced the reality of its short-term commercial viability, leading to a significant market correction. The worry is that the AI market is experiencing a similar disconnect between valuation and immediate, sustained profitability.

Arthur C. Clarke said that “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

For a little magic trick, I’m going to let Google’s NotebookLM summarize this post as written thus far. The male and female voices are synthesized, of course.

Here are the first two minutes of their take:

My reaction to that uses a British schoolboy exclamation from the 1920s: “Wizard!”

So, inspired by Dorothy’s little dog Toto, I’m going to try to pull back the curtain.

People way smarter than me had comparable reactions of astonishment when they first encountered the chatbots.

Distinguished neuroscientist Terrence J. Sejnowski put it:

Something is beginning to happen that was not expected even a few years ago. A threshold was reached, as if a space alien suddenly appeared that could communicate with us in an eerily human way.

If we go way back — as in “In the Beginning” back — something comparably weird apparently happened when language itself appeared among Homo sapiens.

As best we can tell, for the first 150,000 years after anatomically modern humans appeared, they bopped around communicating more or less as chimps and bonobos do today.

Now, chimps and bonobos are smart. But like wise guys, they ain’t talking.

For ‘anatomically modern’, let’s substitute ‘hardware-complete’.

Only around 50,000 BCE was there, among Homo sapiens, a sudden explosion of symbol use.

Same ‘anatomically modern’ brain.

It appears to have been some kind of software revolution.

My three AIs — ChatGPT, Perplexity and Google Gemini — use what are called large language models (LLMs).

To be clear — this is important to remember — LLMs are just one AI technology.

But ChatGPT, which uses an LLM, has gotten the lion’s share of human attention since it appeared in November 2022.

What amazed about the LLM chatbots was that they strung together words and sentences that felt like they are coming from a human.

Which brings up some seriously thorny and — to humans — uncomfortable issues in epistemology. What exactly do these things know?

Here’s my quick take.

First off, I think it’s a mistake to talk about AIs learning.

They’ve been taught.

By us.

Not unlike what we do with children.

With the LLMs, humans have given birth to a novel species of cultural technology.

Some bits of human cultural technology are pretty major. We invented writing. The printing press. Markets, even.

Let’s draw back the curtain a little more.

As computer programs go, the code used in LLMs is surprisingly simple.

They loop and do a zillion matrix multiplies, preferably in parallel.

The secret sauce is what they’re doing it on.

That’s a seriously vast corpus of human-written text.

Which the tech companies could only get their hands on — royalty-free, although that’s in court — some years into the internet era.

The text, usually complete sentences, is broken into segments or ‘tokenized’.

Those tokens are then relentlessly analyzed against each other to compute probability distributions.

How vast is vast?

After filtering and preprocessing, in 2022 GPT-3 looked at approximately 1.2 terabytes (TB) of text.

In 2024, LLaMA 3 was trained on 15 trillion tokens, roughly 60 TB.

For a reference point, the amount of material available digitally from the Library of Congress, which includes photos and audio, is around 74 TB.

What an LLM ‘knows’ about are sequences, ultimately of words.

More precisely, a large language model is a parametric probability model of token sequences.

Not that that does us humans much good.

An LLM’s ‘wisdom’, as distilled from the internet, is a bunch of numerical weights that mean nothing to us.

We humans don’t understand anything until an LLM starts generating output.

Then, it is essentially guessing — perhaps incredibly well — at what comes next.

So a first big epistemological question is: Is guessing correctly knowing?

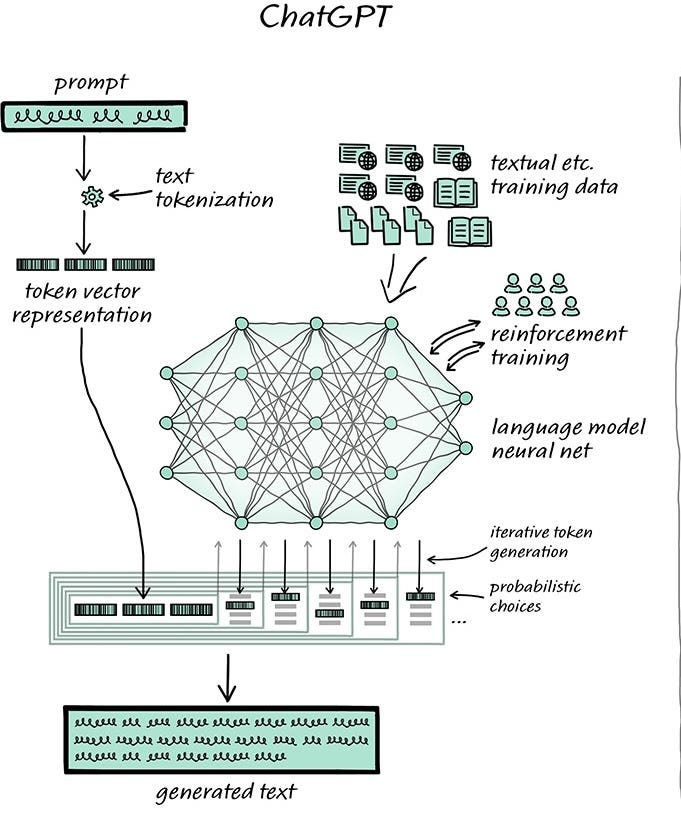

Let’s take a closer look at what Toto sees when he pulls back the curtain:

As the flow from top suggests, there are two things going on with an LLM.

Inference is what happens when you ask an AI a question, or give it a prompt.

Aside: Inference is also what Google is now doing for you when you type in a few words of what once would have been a keyword search. Like it or not.

Inference takes non-trivial compute resources, but building a model— that spidery network in the diagram — is the big one.

That’s what takes the enormous amounts of GPU time and electricity we keep reading about.

Indeed, the amount of electricity used by an AI data center measured in gigawatts has become — oddly if you think about it — the metric for the center’s brainpower.

As a deficiency of vitamin B can lead to problems in childhood brain development, a scarcity of electricity seriously threatens to retard the brain development of AIs.

And the share of compute resources taken by inference is on the increase, causing new problems in AI business models.

What an LLM is doing may look like a glorified version of auto-complete.

And it’s distantly related to that.

But there’s a significant difference, one that gives human fits.

Humans understand that the word ‘cat’ is very likely to come after the word ‘purring’.

But the LLMs are not working at that syntactic level. They’re working deeper than that.

And their output, being determined probabilistically, is not deterministic.

Humans have it in their head that ‘good’ computers are predictable.

Preferably, in fact, slavishly predictable.

The same prompt to an LLM can generate a different answer.

Or a completely bogus one.

On occasion while laying down their words, the LLMs can run completely off the rails.

They just babble. Or hallucinate. Make stuff up.

So they’re hardly consistent.

We don’t like that.

Well, it was a human, Ralph Waldo Emerson, who said “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”

The LLMs are anything but little.

A seminal technical discovery of the 2010s was: massively increasing the scale of LLMs got them to work.

Which came as something of a surprise. Scaling up was one of those things the tech types just tried. And, by golly, it worked.

For several iterations after that, scaling up again made the LLMs work even better.

The number of parameters used by a model is a rough measure of its raw horsepower.

GPT-3, in June 2020, used 175 billion parameters.

In February 2025, GPT-4.5 used 1.7 trillion.

Opinions among the cognoscenti vary, but there’s general unanimity that each new model has improved upon the previous ones.

To date.

A very big questions in contemporary AI is: Just how long — and how far — can this LLM improvement go on?

That’s at the heart of what’s called the scaling debate.

Scaling up has worked so far.

Ergo, one side concludes, more of the same — more parameters, more computing power — will produce ever more capable AIs.

Note that a third ingredient — the secret sauce, the text corpus — is not on that ‘more’ list.

The public internet, in English, isn’t getting much bigger.

Although training LLMs in other languages — or on specialized text, such as medical journals — is a wide open opportunity that’s now getting lots of attention.

The skeptics assert that scaling up will run into diminishing returns.

Or, alternatively, hit some technical ‘wall’.

Now, Moore’s Law has to do with making things smaller, so it doesn’t really apply here.

But — as in every discussion of future tech — it lurks.

For decades, the improvement in semiconductors felt like it would never end.

That finally hit a ‘wall’ when the physical distance between the circuits got down to the angstrom level, a few atoms wide.

Those who say there is ‘no wall’ in AI argue that future gains are likely if investment continues.

Which contains a hint that the ‘wall’ might be economic, not technical.

Big new general LLMs are often called ‘frontier’ models, as in ‘breaking new ground’.

Training them doesn’t come cheap.

Google’s Gemini Ultra, released in 2023, cost some $191 million to train.

Meta’s Llama 3 (“400B model”) cost around $246 million to train.

The time required — during which tens of thousands of GPUs are running flat out — is in the neighborhood of 3 months.

Not unlike the new Oldsmobiles back in the day, each new model is a big deal. They get press coverage.

Bringing up new model Oldsmobiles may sound facetious, but relates to an actual quandary for companies in the AI business. Is there anything that will lead to brand loyalty?

Or — as a car may just be basic transportation — will consumers perceive one model to be as about as good as another?

It’s also, potentially, a big issue in AI company cost accounting.

If, in order to hold customer interest, a company has to come out with a new model every year, it’s got a recurring cost, not a one-time fixed one. The latter is a capital expense, while the former comes under operations.

So the LLMs have given the green eyeshade crowd a lot to think about.

But investing in ever-bigger models is, to some extent, a faith-based activity.

For the believers, we have a path before that leads to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI).

If we choose to take it.

As a sort of lodestar goal, getting to AGI is in the mission statements of a number of the tech giants, notably OpenAI, Google, xAI, and Meta.

Like most states of bliss, AGI is a little vague.

Wikipedia says we’ll have AGI when individual AIs “match or surpass humans across virtually all cognitive tasks.”

Fine. Who am I to argue with Wikipedia?

I need to add that I’m personally doing my bit to bring about AGI in the next decade.

I’m lowering the bar for those AIs by getting stupider every year.

Now, the answers to my question “The contemporary AI bubble is like ____ ?” weren’t wrong.

But it’s worth asking why we assume they will be unsatisfying.

“Alexa? Why do my eyes glaze over when I talk to ChatGPT?”

She’s not quite sure how to help me with that.

At least she knows what she doesn’t know.

I think one sense is: we’re not going to get anything new here.

It was one of the original axioms of information theory that surprising, less probable events have more information content.

Given that the LLMs are trained to generate the most probable sequences, what they come up with is almost guaranteed to be made up of the conventional wisdom. They’re ‘thinking’ inside the box.

Even if it’s a very big box.

The Wikipedia entry “Railway Mania” (here) begins:

Railway Mania was a stock market bubble in the rail transportation industry of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in the 1840s.

so you know the LLMs are going to pick up on that ‘bubble’.

A trick to break out of this is to try to come up with provocative prompts.

I asked my three chatbots “Where does AI slop come from?”

I mean, if you want an answer, you might as well go to the source.

Although I did feel a little guilty about asking them that one.

But I’ve also asked them other questions that torment me, such as “Why do bad dogs happen to good people?”

The answers on the origins of AI slop were pretty decent. And, as usual, pretty consistent.

They blamed people, for one thing.

Which is fair.

It’s not their fault if we’ve put productivity tools in the hands of people who write spam emails.

They underscored one thing I sort of knew but hadn’t quite put together in my head.

It’s the sort of thing I find them actually useful for.

That particular thing was the potential feedback loop that might happen if the LLMs start training on an internet full of output from other LLMs.

We’ll have an autonomous circle of slop.

If LLMs are guessing at what comes next, so are corporate CEOs.

No corporate CEO wants to be the guy who guesses wrong and under-invests in AI, relative to the competition.

Sundar Pichai, of Alphabet (which owns Google) put it succinctly in 2024: “The risk of under-investing is dramatically greater than the risk of over- investing.”

Satya Nadella of Microsoft has said much the same thing: you either run in the pack or risk “being outmaneuvered.”

That fear of being left behind with a comparative disadvantage has fueled an arms race in AI capital spending, capex for short.

Not just among the U.S. tech giants, but among entire nation states.

So an old-school arms race, too. I’ll try to get to that.

The total capex spend on AI by the U.S. tech companies this year looks to be around $371 billion.

That’s up from $125 billion last year.

And several companies have warned their shareholders they intend to spend more in 2026.

The big four U.S. spenders are, in no particular order, Meta (Facebook), Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet (Google).

Apple has basically declined to jump into the race. Time will tell if Apple is making a good call on that.

Apple can always rent rather than buy. Another thing I’ll try to get to.

Here’s the increase in capex over the last few years, in a chart:

And here are some more recent factoids in prose:

In October 2025, Meta said that its capital spending allocated for AI infrastructure would total between $70 billion and $72 billion this year. That’s up from the $65 billion it said in February.

Microsoft has allocated $80 billion to build out AI data centers “to support training advanced AI models and deploying those models to the cloud.”

In October, Amazon upped its 2025 estimate for capex to $125 billion, although not all of that will go toward AI computing capacity. Amazon’s Chief Financial Officer Brian Olsavsky told Wall Street analysts to expect the company’s capital spending to be even higher in 2026.

In September, Alphabet raised its capital spending guidance to $85 billion for the year. For just one example, Alphabet is in the middle of building a $9 billion AI and cloud infrastructure center in Stillwater, Oklahoma.

Now, those billions may sound like a bubblicious amount of money, and they are.

But we have to remember that these companies have other lines of business that are extremely profitable.

For Meta and Google, it’s advertising; for Microsoft, software; and for Amazon, on-line shopping.

The source of the capital — and its ‘quality’ — makes for a big difference between what is going on in AI today and what went on in the 1990s.

Then, most of the ‘Pets R Us’ burning through investor cash had little or no revenue.

The number you wanted to know was called the burn rate, which was how many months a company had left before it ran out of money.

The mantra of the 1990s gold rush was ‘get big quick’. The idea was to stake a claim in cyberspace before the competition did.

Working that claim — worrying about revenue and profit — was for later.

It was a high-risk, high-reward game.

But if a start-up could secure a monopoly in some ‘space’, it could leave the game owning a Facebook.

The contemporary commentariat, being drama queens, love the ‘bubble’ word a little too much.

They’ve found they can juice up the drama if they mix up 1999 and 2008.

The difference goes back to creative destruction.

2008 was a financial bubble.

What we had in the late 1990s was a capital spending boom.

During a capital spending boom, companies like WorldCom can — for sure — get out ahead of their skis.

And bad things can happen to them

But if they implode, it’s an effervescent pop in the froth. The tide surges forward.

In the current AI gold rush, there’s really only one company playing by the old 1990s rules.

And that company is OpenAI.

OpenAI was founded as a nonprofit in San Francisco in December 2015.

Its self-described mission was “to advance digital intelligence in the way that is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole, unconstrained by a need to generate financial return.”

That will come back to haunt.

There was also, interestingly, always a ‘Doomer’ clique inside OpenAI.

The Doomers viewed AGI the way some physicists at Los Alamos viewed the atomic bomb.

As a technical problem, AGI was irresistibly fascinating.

But if achieved, the Doomers feared it could potentially have catastrophic consequences.

At OpenAI’s founding, lead founder Sam Altman put out a press release that the venture had $1 billion in ‘pledges’.

Altman had been the leader of Y Combinator, an incubator that starts start-ups. He was well-connected, with an extensive network.

That’s Silicon Valley’s version of being mobbed-up.

One pledge came from Elon Musk. Another was made by Peter Thiel.

For Altman, the implied $1 billion valuation of OpenAI was the real reality.

Especially after it got some play in the media.

No matter that by 2019, only $130 million of the $1 billion in pledges had actually been collected.

Altman worked hard to create an aura: OpenAI was moving fast.

So fast, such boring details would soon be in its rear view mirror.

Tech journalists covering Altman and OpenAI soon learned that every number and every deal announcement came with an asterisk.

But as a nonprofit, OpenAI did attract some exceptional technical talent from a cadre whose ethical concerns disinclined them to work at places like Google. The company was called ‘Open’ AI for a reason.

The researchers produced progressively better GPT models.

In December 2022, OpenAI found itself with a surprise hit on its hands.

ChatGPT’s website had 265 million visits that month.

Now, there was serious, real research behind the better GPT models.

But I suggest the ChatGPT phenomenon was more like what a company might have with a hit game.

Everybody had to try it.

Especially if it was free.

A year after ChatGPT’s big success, on November 17, 2023, OpenAI’s board tried to fire Sam Altman.

A blow-by-blow account of that squabble — in a little too much detail for my taste — is given in Karen Hao’s book, Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman’s OpenAI.

The board backed down and reinstated Altman within a week.

But before we consign that kerfuffle to the dustbin of history, we need to note one reason given by the board for firing Altman: “Exhibits a consistent pattern of lying.”

Fast forward to January of this year, 2025.

On his first day in office, President Trump shared a podium with Altman at the White House to announce Stargate, a $500 billion AI data complex OpenAI says it’s going to build in Abilene, Texas.

I won’t wade into the weeds on Stargate myself, but I will quote Elon Musk on it.

Although I do first have to mention, as an aside, Mark Nelson’s calculation that each of the Stargate clusters will require an amount of electricity comparable to that produced by six Vogtle-size AP1000 nuclear reactors.

Elon Musk, we should recall, was in at the beginning of OpenAI.

And in those DOGE days of January, he was also a friend of Trump.

Musk is not exactly known for mincing words. He called Stargate a “fake” and Altman a “swindler.”

Now Musk, of course, may be taking his own book. He set up an answer to OpenAI — xAI — in July 2023. It released its own chatbot, Grok, on November 4, 2023.

And Musk, Altman, OpenAI, et. al. are involved in various lawsuits.

But with the Stargate announcement, Altman had the press release he wanted.

Which was the thing.

Every big headline number amps ups OpenAI’s valuation on Wall Street.

The most suspenseful race in artificial intelligence right now — in my opinion — is not between the U.S. and China.

It’s whether OpenAI can make it to an initial public offering.

Before it gets called out on all its promises.

OpenAI might have $13 billion in revenue this year. In 2024, it had about $3.7 billion.

That $13 billion figure comes with the customary asterisk. We basically have only Altman’s say-so for it.

If you parse a recent post on X by Altman carefully — which you must do — he’s upped that $13 billion to a $20 billion ‘run rate’.

A run rate is computed by taking the revenue on your last, best month and multiplying by 12. It assumes things are only going up.

Against that revenue, OpenAI this year has expenses of roughly $2 billion for operations and $6.7 billion for R&D.

By some calculations, OpenAI loses money on every ChatGPT query.

Onto that situation that we must layer on Altman’s assertion that OpenAI will spend $1.4 trillion — that’s 1,400 billion — on capital and infrastructure in the next few years.

Where’s that going to come from?

If we rule out debt financing — which I think any sane lender will do for us — the only remaining option is investors, mostly retail investors.

They would presumably go for OpenAI as a some sort of AI meme stock.

An IPO is the only thing that will allow OpenAI to convert its principal asset — its mindshare — into investor cash.

If AI bubble is still bubblicious next year, one estimate is that OpenAI might raise $600 billion from an IPO in 2026.

If the company can hold out until 2027, there’s speculation it might raise $1 trillion.

Such a Cinderella ending that would vault OpenAI into a very exclusive club, since there are only nine U.S. corporations whose market values exceed $1 trillion.

At least all of those announcements with their boring details would definitely be in the rearview.

To get her happy ending, Cinderella must overcome the usual obstacles.

In the lead-up to an IPO, OpenAI’s books would presumably get some serious vetting.

And not all IPOs are successful. Some do fail.

There’s also a non-zero possibility that OpenAI will implode on its own before then.

From something to do with Altman personally, for example.

In that instance, the shards would most likely be absorbed by Microsoft.

Which, so not to bruise egos, would be styled as an acquisition.

Altman would like to go down in history as AI’s Steve Jobs.

There’s a chance he may go down as its Jay Cooke or its Jay Gould.

Those were the 19th century U.S. railroad financiers who set off several panics.

The failure of Jay Cooke & Company set off one in 1873. That one closed the New York Stock Exchange for ten days.

Don’t get me started on Jay Gould. Let’s just say his career in the Gilded Age proves that the Bond villain was actually a 19th century invention.

In 1841, Scottish journalist Charles Mackay published a book now known as Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.

It’s of course in the public domain. Here’s a link to the Wikipedia entry for it.

Mackay’s entertaining history looks at the 17th century Dutch tulip mania, the British South Sea Bubble of 1711–1720, and so on.

A chapter whose title I particularly like is: “The Love of the Marvellous and the Disbelief of the True.”

In every bubble, there are two realities.

Let’s call one real reality.

And then there’s whatever is going on in people’s heads.

Today — not in 1841, of course — what’s echoing around in Wall Street’s head are voices picked up from podcasts, YouTube videos, the financial media, and the like.

Not unlike the way an LLM picks up everything and repeats it back at you.

Which starts to feel very hallucinogenic.

To preserve my sanity, I decided to take action: ignore everything Sam Altman and OpenAI had to say.

Wall Street, looking at AI, is like someone staring at an optical illusion.

First it sees one thing, then another.

Recently, it’s been mesmerized by spinning circles.

In March 2025, Nvidia invested in CoreWeave, an AI data center operator.

CoreWeave, in turn, is a big buyer of Nvidia GPUs.

Bryce Elder of The Financial Times thought he saw an ouroboros.

That’s a snake or dragon eating its own tail:

In the ultimate ouroboros, on September 22, 2025 Jensen Huang said Nvidia was willing to put up to $100 billion into OpenAI, which would use it to buy Nvidia chips.

An infographic full of circles was published by Bloomberg on October 22, 2025. It’s behind Bloomberg’s paywall, but the link is here. The diagram has become slightly famous:

For my little thought experiment, I erased OpenAI from the picture.

Then I saw something different.

I saw a star, with Nvidia at its center.

It’s a pattern that’s a bit foreign to American capitalism, but not in Asia.

What we’re looking at is a keiretsu in formation.

In Japan, the keiretsu are corporate groups larger than the individual companies that make them up.

The companies of a keiretsu take ownership shares in each other, a practice that drives Western economists crazy.

Japan’s zaibatsu got blamed by the Allied Occupation for egging on World War II, so the modern-day keiretsu are their kindler, gentler vestige.

In Korea, comparable corporate groups, usually family-tied, are called chaebol.

To some extent, companies in a keiretsu will bail each other out, if things go bad for one of them. Western economists would prefer the losers to fail and be done with it.

There’s a competition in AI going on between the U.S. and China.

Not to get all patriotic on you, but I think Team America should be happy to have the Nvidia keiretsu on its side.

Nvidia is a real company with real products, real revenue and real profits.

At the moment, it has 90% of the market for AI GPUs.

Which is like being the gold rush storekeep who has the exclusive franchise on picks, shovels and tents.

In its third fiscal quarter of 2025, Nvidia had revenue of $35.1 billion and net income of $19.3 billion.

So it has some cash to play with.

A few writers have gotten worked up about Nvidia making investments in companies that are its customers, or are likely to become its customers.

It’s a slightly new twist on vendor financing.

About which there’s nothing new, or inherently sinister.

If you’ve flown on a Boeing jet or let a dealership finance your car, you’ve participated.

GE Capital still finances the sale of jet engines to airlines through GE Capital Aviation Services.

GM set up General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC) in 1919. It’s the ancestor of current-day Ally Bank.

True, in the 2008 financial crisis the U.S. Treasury felt compelled to take a $17.2 billion stake in GMAC.

But the Treasury sold that stake in 2014 at close to a $2 billion profit.

And yes — reminiscent of the earlier bubble of your choosing — more debt financing of AI infrastructure is starting to appear.

Some of it from the standpoint of financial engineering is a little exotic.

We’ve seen off-balance-sheet deals (Meta), and private-finance loans to data centers collateralized by their own GPU chips (CoreWeave).

Meta recently used an entity called Blue Owl Capital to issue the largest ($27.3 billion) corporate bond in US history.

That will finance Meta’s Hyperion data center in Richland County, Louisiana while keeping that $27.3 billion off Meta’s books.

In the event the AI bubble pops dramatically, it will be Blue Owl, not Meta, that goes poof.

As for CoreWeave’s loans — from private lenders and collateralized by its GPUs —yes, GPUs do go out-of-date.

But GPUs are not subprime mortgages.

Past bubbles teach us there can be plenty of Sturm und Drang among individual companies on Wall Street. They can fail.

The trillion-dollar question is whether the failure of any one of non-tech giant AI companies would have Lehman Brothers–size consequences on the entire economy.

I’m not clutching my worry beads too tightly about that one.

Creative destruction, I suspect, would come to the rescue.

Those GPUs would get used for something.

I like happy endings.

So let’s write one for the AI bubble.

A hint came in ChatGPT’s follow-on suggestions to my opening prompt.

Let’s look at AI as being like electrification.

And not think about the AI bubble popping, but all the talk about it slowly deflating.

Now, that outcome need not be good for individual companies.

One scenario common in tech is profitless prosperity.

Something ubiquitous, such memory chips, becomes a commodity.

Everybody has more than they need (the prosperity), and no manufacture makes any money on them (the profitless part).

We can see AI ubiquity happening before our eyes with web browsers. Those blue-underlined hyperlinks are becoming a thing of the past.

I liken it to a changing of the guard at the Information Desk of the public library.

In the old days, if you had a question on some subject, they’d point you to a location in the stacks where you might find a book with an answer.

These days, they just answer your question. The LLMs have read all those books.

Does this disrupt the business model of Google and of web publishers, who count on people seeing ads to make money? Of course it does.

I’ll cry a little for the web publishers, whose content is getting scraped by the LLMs.

But not very much for Google, who a few years back intentionally started making its search results worse to expose users to more ads. See Cory Doctorow’s recent book for the unpleasant details.

Back to electrification.

It had some spectacular early successes.

On the evening of April 29, 1879, the city fathers of Cleveland flooded Monumental Park with light when they switched on a bunch of arc lamps.

But after lighting and electric streetcars, it took decades to figure out the best way to use electricity.

That didn’t really come until the 1920s, when factory owners realized they had to restructure production lines to take advantage.

Then the U.S. economy got a big productivity boost.

Electrification wasn’t the only capital-spending boom to have a time-delay fuse.

In 1987, M.I.T. economist Robert Solow — who won the Nobel Memorial Prize for economics that year — made a famous observation: “You can see the computer age everywhere,” he said, “but in the productivity statistics.”

By all accounts, at the moment demand for GPUs and ‘compute’ is off the charts.

That part of the boom is real.

But recall that what the LLMs are doing means nothing to humans — until we see their output.

The staying power of our demand for that is an open question.

At the moment, most of the chatbots have free tiers, although some consumers take monthly subscriptions to play with the GPTs.

But the real money will have to come from so-called ‘enterprise’, or business subscriptions.

Those business will ultimately have to see a return on investment — ROI — to keep those subscriptions renewed.

That question has no single answer.

It’s one use case at a time.

As in figuring out how to use electricity, those little solutions require human effort, ingenuity and time.

In the foreseeable future, AIs will be augmenting human workers, not replacing them.

The most obvious use cases involve language.

Foreign language translation by computer — sadly for human translators — is probably ‘good enough’, if it doesn’t have to be literary or legal grade.

The ability of AIs to write in computer language, so-called ‘vibe coding’, is reportedly pretty good — although what they generate needs to be checked by someone who knows what they are doing.

In other office work, being able to get productive results from an AI is a human skill, not unlike being able to get something of value out of an intern.

They may be eager, but they can screw up.

But the CEOs who look forward to firing their office workers and replacing them with AIs are in for a disappointment. Or they have been drinking too much of Wall Street’s Kool-Aid.

Likewise, the much-ballyhooed idea of trusting an AI agent to do everything for you seems to me laughable at this moment.

I’ve had a highly intelligent and trustworthy human assistant, and can count on one hand the number of times I handed her my credit card and said, “Put it on this…”

But, like I said, I have trust issues.

Journalist Evan Ratliff has a very amusing podcast series called Shell Game.

Ratliff created a fictional start-up whose employees are all AI agents, such ‘Kyle Law’ and ‘Megan Flores’, the latter head of marketing.

In a Wired article (here) about his start-up, Ratliff recounts:

At first it was fun, managing this collection of imitation teammates — like playing The Sims or something. It didn’t even bother me that when they didn’t know something, they just confabulated it in the moment. Their made-up details were even useful, for filling out my AI employee’s personalities.

Ratliff even cloned himself into an AI to delegate managing them.

Returning to ‘human effort and ingenuity’, AI— like the internet before it — may provide a much-needed excuse to rethink workplaces that really need it, such as education and health care.

But the vested interests are deeply vested.

I’ll get hate mail for this, but I find what the Alpha Schools are doing to be fascinating.

Alpha Schools are expensive ($40,000 a year in Austin) private schools that use AI tutors.

They claim they can reduce instruction time to two hours a day — with, they say, fabulous results. That frees up kids for afternoon sports and ‘life skills workshops’.

In the U.S., somewhere around 25% to 30% of health care spending goes to administration, billing, insurance processing, and the like.

That’s going to take a general restructuring, not a few chatbots, to fix.

I can sympathize with anyone who loses a job.

Whether it’s really to AI, or actually the fault of some corporate CEO who is using AI as an excuse for old-school “Chainsaw” Jack Welch–style cost-cutting, a recent phenomenon known as ‘AI washing’.

Nor am I a big fan of Big Tech’s extreme concentration, and its extractive nature. On that, see Tim Wu’s recent book, The Age of Extraction: How Tech Platforms Conquered the Economy and Threaten Our Future Prosperity.

But that huge trend has been going on in American capitalism since a sea-change in the mid-1970s.

Carter C. Price, a Senior Mathematician, at RAND, has calculated that if incomes of the bottom 90% of workers had been divided with those of the top 10% at the exact same ratio they were in the 30 years after World War II, with the growth of the economy the 90% would now be cumulatively better off by some $80 trillion.

On that scale, the technology bubbles are but foamy crests on a Kondratieff wave.

The bubble may go, but AI is here to stay.

Get used to it.

Just a few years back, pundits were bemoaning how little capital spending American corporations were doing to increase worker productivity.

Well, for better or worse, now we have it.

If you don’t like what’s going on in the economy, organize. But I don’t think Luddism is any more a viable strategy today than it was in the 1820s.

Maybe you can figure out how to get the AIs to help you.

Meanwhile, enjoy the good times.

Not everybody gets to live through a decade like the Roaring Twenties, the 1960s, or the 1990s

So party like it’s 1999. As long as it lasts.