You would not want to take a road trip with me.

First, no eating in the car.

Second, no big debates about the best way to get somewhere. I cut people off on that.

That’s because the lady trapped inside my car’s navigation system is (a) really smart (b) has a nice voice and ( c ) has the infinite patience of my favorite grade school teacher, Miss Nordquist.

If I screw up and miss a turn — which, I confess, has happened — She evinces no blame, shame or recrimination.

Just “Recalculating route.”

So we follow Her orders. No talking back.

Last June, on a drive from Austin to Los Angeles, I discovered Her knowledge base goes deeper than I thought. It evidently includes seismology.

The tank was running low, so when approaching Midland, Texas, I asked Her to “Find gas near here.”

She took me down a series of gravel roads to an industrial fracking site.

Aside: Judging from amount of truck traffic I encountered on those gravel roads the oil patch is doing just fine.

She had no problem landing me at my other off-beat stops, such as the International UFO Museum and Research Center in Roswell, New Mexico:

You have to admit there are a lot of unanswered questions about UFOs.

One I have is: Why ‘International’ UFO Museum, anyway? Shouldn’t it be ‘Interplanetary’ or something like that?

She could only get me close to Ground Zero of the Trinity atomic bomb test site in New Mexico. I had to get out of the car and start hoofing it across the White Sands.

Only to get stopped in my tracks by a very polite, and very bored, female military police person.

At least we had a nice chat. Turns out the public is allowed to walk on Ground Zero only two weekends a year. Mine wasn’t one of them.

I make a point of stopping at any nuclear power plants along the way. She’s not too bad at finding those.

I took the photo at the top looking toward the Palo Verde Generating Station just west of Phoenix, Arizona.

If you look closely, some those bumps along the skyline are symmetrical — the containment domes.

But the most interesting roadside attraction of my June trip is right there in the foreground.

I hadn’t driven Interstate 10 in a few years.

The desert landscape has changed.

What you see heading west, starting in Arizona, are miles and miles of solar panels.

I mean miles.

Getting an elevated view helps appreciate it. Here’s a drone shot from Nevada:

My road trip came to mind on November 24th, when I read a article in the Los Angeles Times under the headline: “Solar power glut boosts California electric bills. Other states reap the benefits.”

The L.A. Times is paywalled, but here’s the link.

News stories need a hook to catch readers’ attention.

The writer, Melody Petersen, has a good one.

CASIO, California’s grid operator, is paying to have surplus solar electricity taken off its hands.

The lucky beneficiaries of this largesse include nearby states, such as Arizona and Washington, and some shadowy figures described in the article only as “electricity traders, including banks and hedge funds.”

For Times readers old enough to remember California’s 2001 energy debacle, that last bit was certain to summon up the ghost of Enron past during the holiday season.

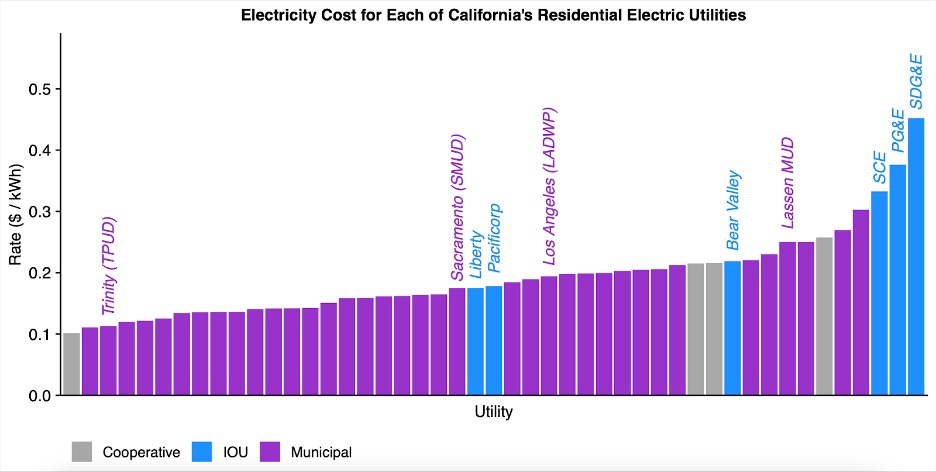

Ms. Petersen’s readers of all ages will undoubtedly be painfully aware that California has the highest electric rates of any state in the country.

Excluding Hawaii, which, being a bunch of islands way out in the ocean, is weird.

Electricity-wise. Otherwise, a great place.

Actually, in November 2024 customers of San Diego Gas & Electric (SDG&G) had the dubious honor of having their electric rates go higher than those of ‘urban’ Hawaii.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (here’s the link), the SDG&G rate is now 42¢/kWh, as opposed to 39¢/kWh in Hawaii.

In general, California residential rates are 50% higher than the U.S. national average, which was 17.6¢/kWh in November.

And California rates are going up faster. I suspect this year we’ll see at least one California utility’s rate break 50¢/kWh, a psychological barrier of some sort.

So whatever CASIO has been doing with all that cheap solar, it hasn’t done anything to bring utility rates down.

This post will require me to translate certain non-English idioms from the California Newspeak.

I’ll do my best. I did grow up there.

When CAISO when pays those neighboring states to take its surplus solar, it credits itself for ‘negative carbon emissions’.

That’s on the theory those states use it to reduce their fossil generation.

Sadly, not entirely true. Those neighboring states are happy to cut back on their own renewable generation, if California’s offer is right.

An interesting factoid in Ms. Petersen’s article is that Arizona Public Service, the utility, operates a 24-hour trading floor in Phoenix always on the lookout for dirt-cheap or negatively-priced solar power.

But you don’t need a complex economic model to explain what’s going on here.

If you subsidize something long enough, you end up with a lot of it.

If you keep on subsidizing it, ‘a lot’ becomes ‘enough’.

Keep on, and ‘enough’ can become ‘too much’.

In the spring of 2024, California electricity crossed a line into new territory.

It’s a ‘fuzzy’ line, to be sure. But a significant one.

Aside: At U.C. Berkeley, one of my math professors was Lotfi Zadeh, inventor of ‘fuzzy logic’. It was always hard to explain to people exactly what I was studying.

April is the kindest month for renewables generation in California.

It’s bright and sunny, but not so hot that people have to turn on their air conditioners.

The snow melt off the Sierras is running hydropower at full flood.

And there’s enough March wind left over that the turbines are spinning madly.

It always helps to visualize ‘fuzzy’ things.

Here’s the line. From ‘100% of load’ on the left, trace right:

Over that line, renewables, mostly solar, were making more than 100% of the electricity that was actually needed, the ‘load’.

An advocacy group, Environment America, which has a ‘Campaign for 100% Renewable Energy’, is presumably no stranger to fuzzy thinking.

They noticed this, too. In July [2024], they held a Zoom jamboree celebrating California passing a ‘milestone’. The star of show was Stanford professor Mark Z. Jacobson, well-known advocate of all-renewables, all the time.

California was once again leading the way, and so on.

Now, I don’t pretend to understand the group’s math.

The Diablo Canyon nuclear plant was running — I checked — and quietly putting out its usual 9% share of California electricity, day and night.

For all of 2023, thanks to Diablo Canyon, Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) delivered its customers in northern California electricity that was generated 53% by nuclear and 13% by large hydropower.

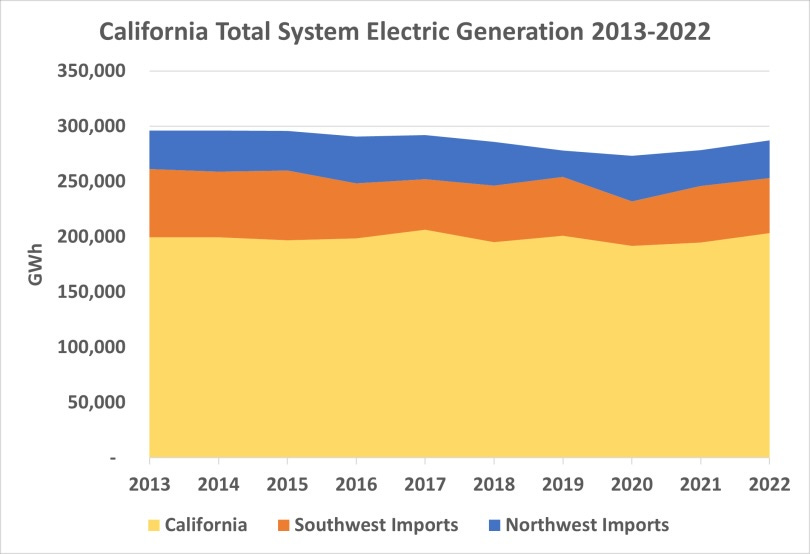

Nor is it clear how the group handled California’s imports of electricity. Those meet 30% of the state’s demand.

Not all of those imports are clean hydropower from the Pacific Northwest.

Electricity generated by coal-fired plants — mostly in Wyoming and owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Energy — tends to get buried in the state’s official statistics under ‘unspecified imports’.

It takes some digging to bring them to the surface. But for of all of 2022, coal produced about 9% of California’s imported electricity and 2.15% of its total power.

The Palo Verde Generating Station — the same I took the picture of — is an under-appreciated, hidden hero of California electricity, by the way. It has bailed out L.A. on many a hot summer day.

Indeed, I suspect the reason so many solar farmers homesteaded along Interstate 10 was to take advantage of the whopping fat high-capacity transmission line built years ago to carry electricity from Palo Verde to Southern California.

Still, bad as their math might be, the zealots are on to something about Californians leading the way.

Although I would phrase it differently.

I would call California’s ratepayers the first canaries being sent into the all-renewables coal mine.

California is about to demonstrate what happens when a state — or country or other jurisdiction of your choice — is hell-bent on increasing solar.

The pioneers are the ones with the arrows in their back.

Or, as William Gibson said, “The future is here, it is just unevenly distributed.”

The dawn of the solar future breaking in California.

It won’t be all sweetness and light.

I always hesitate before writing the phrase ‘California’s energy policy’.

That’s because people will assume there's an intelligence behind it.

There isn’t.

It’s an emergent phenomenon which evolves, like some swamp creature, out a potent mash of mandates and market.

The market part appeared after 1996, when California became the first state to deregulate its electricity market.

Some of swamp creatures of that era you would recognize today, although a few are diminished in size.

California’s electricity, then as now, came from (a) one of the three big investor-owned utilities — Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), Southern California Edison (SCE), and San Diego Gas & Electric (SDG&E) — or (b) one of a municipally-owned utilities, of which the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADPW) and the Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD) are significantly large.

The LADPW is the largest municipal utility in the U.S.

Here’s a list of the ‘load serving entities’ sorted by average rate. The big three investor-owned utilities have the highest:

Aside: ‘Investor-owned utilities’ is sometimes abbreviated IOU. That may relate to either (a) the considerable number of customers they have who are behind on their bills, or (b) short for ‘intransigent, obstinate, and unwilling’.

The utility monopolies, then as now, were regulated by a public utilities commission, whose acronym in California is the CPUC.

It's a bit lazy to dismiss the CPUC as a ‘captive’ of the industry it regulates. But it definitely tends to be sympathetic.

California’s state politicians are definitely denizens of the swamp.

In 1996, they were gung-ho — at least verbally — in favor of deregulation and a market.

Deregulation under Carter and Reagan had worked in certain industries. Consumers got lower airfares. They got to choose a long-distance company.

A trading market for electricity in California would drive down utility rates for consumers and save billions. Or so Enron executive Jeffrey Skilling testified to the CPUC in June 1994.

Consumers would get ‘retail choice’. They’d no longer be compelled to buy from a monopoly utility.

Which fell on willing ears.

By the mid-1990s, decades of anti-establishment politics had built up a lot of hate toward the utilities.

They were complacent and haughty. The investor-owned ones mainly cared about making their quarterly dividends for shareholders.

As for business culture and efficiency, they eventually got the job done, but more in the way the U.S. military or the Post Office does than Amazon or Federal Express.

Anyway, definitely part of The Establishment.

California’s Greens really, really hated the utilities for one more reason: they had built the nuclear plants.

San Onofre was opened by SCE in 1968 and Diablo Canyon was opened by PG&E in 1985, after 15 years of delays from various protests and legal challenges.

The Greens were all-in for deregulation, right alongside Enron.

Deregulation would split up the vertically-integrated utilities into three layers: generation, transmission, and retail distribution.

Enron’s interest, at least, was transparently mercenary.

The company had its eye on the tens of billions of dollars that flowed from the ratepayers into the utilities. It wanted to cut itself in on that.

The Green’s thinking was more subtle.

The ‘book’ on electricity deregulation had been written in 1983 by two MIT economists, Paul Joskow and Richard Schmalensee: Markets for Power: An Analysis of Electric Utility Deregulation.

The two famously predicted that deregulation would create a ‘missing money problem’.

It’s complicated, but take their word that “a short-run marginal cost market will not support capital investment.”

For the Greens, the ‘missing money’ was an opportunity.

They would starve the utility beast.

No utility in California would be able to finance a nuclear plant again.

And none did.

Aside: The ‘missing money’ showed up 20 years later, when two decades of under-investment by the utilities in their transmission lines started sparking off wildfires.

California state politicians, then as now, were a bit wishy-washy in their free-market faith.

From the class notes to Econ 101, they vaguely remembered that a market, when supply is inadequate to meet demand, will raise prices.

The voters might not like that.

So they wanted to keep their hand in the market, in case Adam Smith’s invisible one got out of hand.

For California Power Market Version 1.0, they put on retail price controls.

That didn’t work out well.

But it’s a long story you can read about in the Wikipedia entry for “2000–2001 California electricity crisis” if you’re interested.

Long story short, the ‘market’ that emerged from the swamp was neither fish nor fowl.

It looked like a market, but one getting a lot of ‘guidance’ from the state.

With a nod to China, I like to call it “a market with California characteristics.”

We can make a short case study of how the mash-up of market and mandates leads to higher costs for the utilities.

Which translate pretty directly to higher rates for the utilities’ customers.

California’s 2013 battery storage mandate, AB2514, instructed PG&E, SCE, and SDG&E to procure 1.325 GW of energy storage by 2024.

The mandate could be satisfied either by the utilities (a) buying something like batteries themselves, or (b) by contracting for storage with third-parties.

So there’s new action in something that looks like a ‘market’ for storage.

But it’s a market in which the utilities are under orders to buy a certain kind of thing, instead of some other thing that might be less expensive.

A market with California characteristics.

For example — in utility jargon — a time slot of the day (and sometimes at a location) for which generation is deficient is called a ’gap’.

There are several ways to plug a gap.

One way to ‘plug’ a gap is to throw in a small amount of generation — a natural gas ‘peaker’ plant, for example.

For short gaps, utility-scale battery farms compete with natural gas peakers.

Under normal circumstances, a utility would probably make the business decision mainly on price.

Under the mandate, on the utility’s list of potential vendors, the battery farms will have a little gold star: this one will help us meet our quota.

Aside from shaping who gets considered, the mandate also weakens the bargaining position of the utility when it gets down to negotiating with the favored vendor.

That might otherwise involve a haggling over price.

When both sides are aware there is a quota to fill, the priority tends to be, just get a deal done.

Fortunately for them, California utilities aren’t terribly bothered when they have to pay vendors higher prices.

That’s because, to justify a rate hike, the best argument in the world they can take to the CPUC is: You — or the legislature — told us to do it.

We were just following orders.

California state politicians never met a Renewables Portfolio Standard (RPS) they didn’t like.

Or at least dared to vote against.

The first one passed in 2002.

It listed in detail the preferred technologies from which the utilities were required get 20% of the electricity they sold to customers: solar, wind, biomass, geothermal, small hydro, tidal currents.

Nuclear, of course, didn’t make the Nice List.

A metric many of us have watched for years has a slightly sexualized name: renewables penetration.

In 2008, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) did a theoretical study of the consequences of “High Levels of Photovoltaics Penetration”.

The NREL’s 2008 idea of a ‘high’ level of solar penetration was 10%.

It concluded that existing grids could handle 10% renewables, mainly because the renewables could free ride on the stability and reliability of the other 90%.

In 2014, with the 20% 2002 RPS set to expire, California state politicians started debating a new one. They kicked around levels of 30% and 50%.

The state’s utilities had a shouting interest in the RPS, since they would be the ones receiving the diktat about what they had to deliver to their customers.

They got together and commissioned a consulting group, Energy+Environmental Economics (‘E3’), to study the likely impact of 30% and 50% RPS levels.

Just for the record, the E3 study was funded by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP), Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E), the Sacramento Municipal Utilities District (SMUD), San Diego Gas & Electric Company (SDG&E), and Southern California Edison Company (SCE).

That 2014 (December 2013) study is still worth reading today. Here’s a link.

The prose is bit dense and takes some close reading, but I’ll quote a few bullet points:

This study finds that overgeneration is pervasive at RPS levels above 33%, particularly when the renewable portfolio is dominated by solar resources.

The quantity of managed renewable energy curtailment increases exponentially for RPS requirements that move from 40% to 50% RPS.

Rate increases are expected to be significantly higher under the 50% RPS scenario […] due to the exponential increase in renewable curtailment as the RPS target increases towards 50%, requiring a significant “overbuild” of the renewable portfolio to meet the RPS target.

None of that hard-to-understand stuff scared off the California state legislators. They voted for the 50% RPS.

In 2018, the politicians upped the ante to 60% renewables by 2030.

And by 2045, the state is supposed to go Full Monty: 100% from renewables.

Aside: If you’ll allow me to be crude, I can put the thesis of the rest of this post in a one-liner: Allow renewables penetration to go too far, and you're screwed.

In the decade after 2014, solar raced ahead of the other renewables on the Nice List.

Wind, for example, basically went nowhere:

Since the 1970s, the energy discussion has dominated by some notion that we don’t have ‘enough’ of something.

Back then, it was of oil.

If you listen to renewables advocates today, we don’t have near enough wind and solar, because, as gets endlessly repeated, we won’t be able to meet our climate goals of [whatever] by [whenever].

In the last fews years, we’re starting worrying about whether there is going to be ‘enough’ for data centers.

The unreliability and weather-dependency of renewables has led to near or actual blackouts, and those shortfalls are also about having ‘enough’.

In a medical diagnosis, you can see the acute incident, but miss the chronic disease.

The which is the result of force-feeding California’s grid a diet of solar.

Think fatty liver disease. Or foie gras.

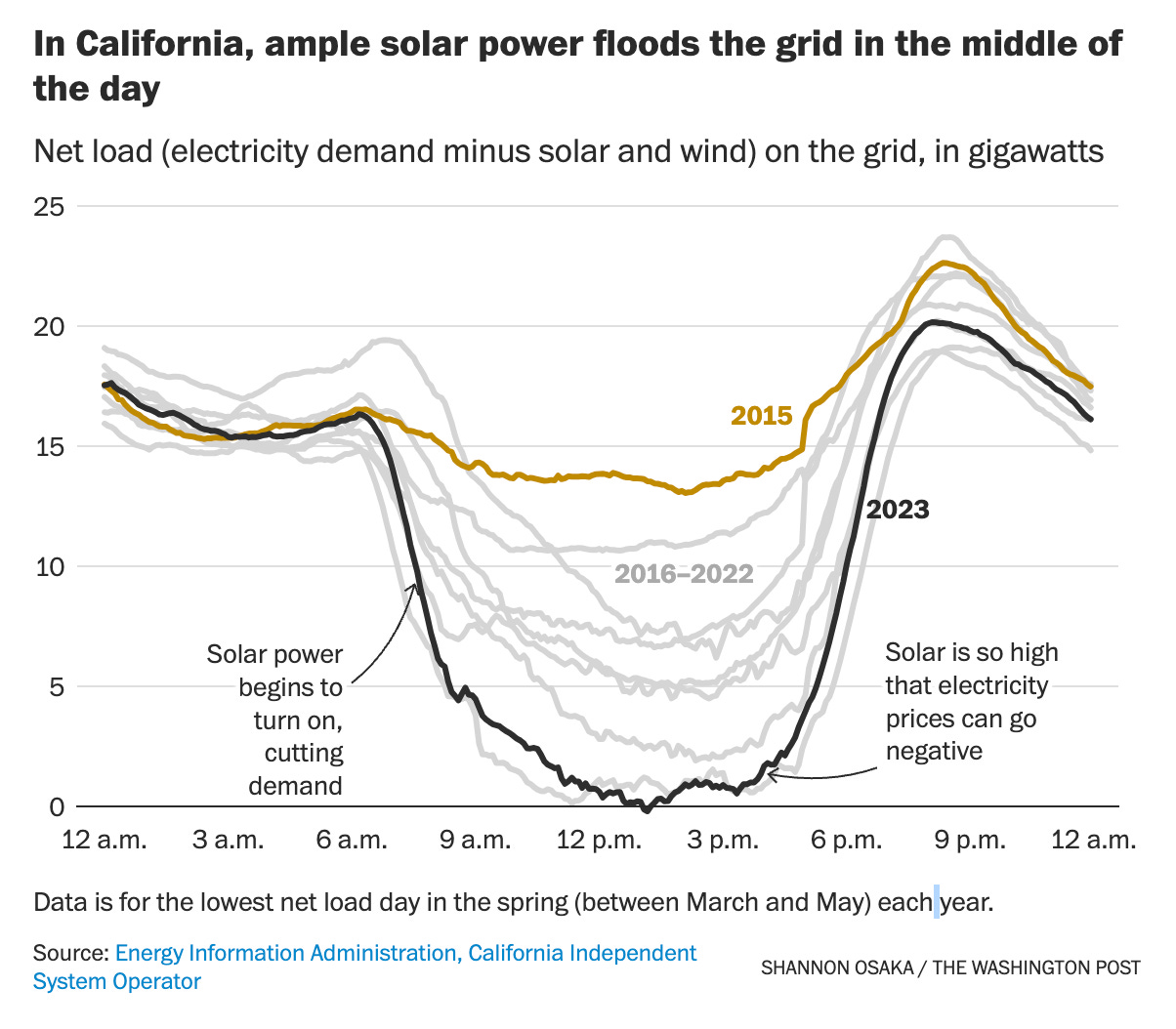

That last comes to mind because the symptom of the disease is the so-called ‘duck curve’. Here’s an X-ray of the duck from mid-2023:

Over the years, the duck’s belly has grown fatter and deeper.

Which — to be fair to the duck — is something anyone might conclude while looking in a mirror.

The fuzzy line that gets crossed more often now by the duck’s extended belly is the horizontal one at the bottom.

Here’s another helping of duck, with day-ahead power prices, around Thanksgiving 2023, a time of year not traditionally associated with either duck or solar. Note the dips below zero into negative price territory:

‘Negative pricing’ is now happening in an average of 18% of all sales, versus about 2.5% in 2014.

Negative prices are a polite way of saying you have so much of something, you have to pay somebody to take it off your hands.

Aside: Don’t attempt to explain this advanced concept to a child. They just won’t get it. Wait until they’re older. The small ones will agree to sell you something they’ve got at a ‘negative price’, and then start crying when you demand their lunch money.

Inquiring minds may wonder what kind of business remains in business if it has to pay its customers to take its product.

Solar farms, for one. They have an incentive to put electricity on the grid even when the price is negative: the production tax credit (PTC).

As I write, the federal PTC is 2.6¢ per kilowatt-hour.

With optional ‘adders’, which depend on a lot of things, such as domestic content, low-income community, and so on. It’s something only an accountant can love. Or understand.

If I’ve kept the decimal places right, a solar generator can still come out ahead even paying someone $26/MWh to take the generated electricity off his hand.

I’ve seen an actual market transaction recorded at -$25/MWh, so perhaps I did keep them straight.

A business in which negative prices appear regularly might also — one might think — give pause to those contemplating getting into it.

That seems to be happening to some extent in Europe. Utility-scale solar is slowing down a bit there.

But here in America, we have the IRA.

I don’t really trust the ‘growth in capacity’ statistics that get bandied about, for reasons I’ll get to below.

Let’s just say the capacity of a solar farm at midnight is exactly zero.

So I keep a folder crammed with announcements about new California solar projects.

From that anecdotal evidence, utility-scale solar — now plus batteries — is being added in California at a rapid clip.

In the jargon, a bunch of big batteries, often co-located with the solar farm, is called a BESS — battery energy storage system.

The unit for the ‘nameplate capacity’ of a solar farm, the one to be taken with a grain of salt, is in MW, megawatts that could be generated by the panels under ideal conditions. Such as it’s a sunny day and the panels are not old or dusty.

The unit for batteries is MWh, megawatt-hours.

Utility-size batteries crossed a fuzzy line of their own at 8:10 pm on April 16, 2024, when, according to CASIO, more electricity (6,177 MW) was fed into its grid in a 5-minute time slot from batteries than from any other source, such as natural gas (5,121 MW), renewables (presumably wind) (4,603 MW), large-scale hydroelectric 4,353 MW), and imports (3,936 MW).

Right now, adding utility-scale batteries to a solar installation approximately doubles its cost.

Now, I’ve got nothing against batteries. I’d like to see research into every possible battery technology.

And if — and only if — you assume we’re stuck with a grid like we have now — a political question — there’s some free-market juju working on behalf of batteries.

A few years of robust sales, maybe with some technology innovation, will probably bring battery costs down.

Aside: Some recent talk about a battery ‘surplus’ and batteries falling very far in price seems to relate to EV batteries, not utility-scale ones.

The monetary opportunity of batteries derives from a simple time arbitrage: store electricity when it’s free or cheap, sell it later when it’s more expensive.

Although I would caution that, as Wall Street traders know, it’s the nature of arbitrage opportunities to self-extinguish. The price differentials don’t last.

So when enough batteries on the grid, the duck will develop a ‘flatter’ shoulder on the evening end.

I don’t know what you call a hunch-backed duck.

And how broad the duck’s shoulders get may depend on which state he’s from.

In California, CASIO’s ‘resource adequacy (RA)’ market for battery-supplied electricity is structured to work in blocks of 4 hours.

Which is different in free-wheeling Texas, where battery power sells in 1- and 2-hour increments.

Anyway, there’s a lot of utility scale solar + storage getting built.

This from a representative December 10, 2024 story on the top of my pile:

Arevon’s Eland 1 solar-plus-storage project near Bakersfield has begun commercial operations.

That solar farm can generate 384 MW of electricity.

The batteries at that Eland 1 site can store 600 MWh.

Eland 2, a second phase of the project, will come online in early 2025. The capital cost of both sites combined is over $2 billion.

If you follow the money in these announcements, you inevitably come across something like this:

The financing was completed using a combination of debt financing and tax credit transfer, which is possible under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Arevon secured a deal with JP Morgan to purchase US$191 million worth of investment tax credits (ITC) and production tax credits (PTC) in one of the first examples of credit transferability in the US.

If they build it, someone is supposed to come.

Some economists say negative prices show a market is working.

Being mean, I’d sentence those economists, Red Guard–style, to a spell of rural re-education.

The historian in me says negative prices show a market being destroyed.

In the early days of the Great Depression, milk prices got so low it wasn’t worth the time of dairy farmers to try and sell it. Here’s a 1933 photo of some in Wisconsin dumping it on a road:

Farm surpluses are not an altogether fanciful analogy for solar surpluses.

If I’d been driving along the Interstate in Iowa, I would have seen miles and miles of corn converting sunlight into starch.

In Arizona, I saw miles and miles of solar panels converting sunlight into electrons.

They’re called solar ‘farms’ for a reason.

If farm policy is any precedent, the solar surplus is going to be an expensive one.

The renewables lobby, as the farm lobby does, will fight any change in the status quo.

So the politicians, as is their wont, will take the easiest way out: throw more money at it. Come up with new subsidies to fix the old ones.

Corn ethanol was a perversely brilliant 1970s solution to an intractable overproduction problem that had plagued U.S. farm policy for generations.

Corn ethanol, of course, has nothing to do with energy independence or greenhouse gas reduction.

It’s ag policy.

Ethanol production now gets rid of 45% of the U.S. corn crop.

Problem solved. But not cheaply.

Not too many years ago — 2010 — the annual ‘tax expenditure’ on corn ethanol was $5.16 billion, by far the largest one in the entire federal budget, according to Congressional Budget Office.

Aside: Politicians love tax expenditures, because the taxpayers never notice them.

The ethanol subsidies have come down a little from that scandalous 2010 level.

And since, in an effort to make that corn alcohol go down smoother, it’s been rebranded green.

But we’re still paying for firms like Archer-Daniels-Midland to make ‘sustainable’ fuel.

And hoping they will figure out how to turn corn into ‘SAF’, sustainable aviation fuel.

If you have a lot of lemons, make lemonade.

The equivalent of dumping milk on the ground is called ‘curtailment’ in solar.

Curtailed power isn’t used by anybody, and — importantly — doesn’t make it into the usual grid statistics. It’s not transacted in CASIO’s market.

I sometimes think of it as ‘dark solar’, but that’s probably just me.

CASIO, the California grid operator, has its own method estimating how much wind and solar are curtailed.

CASIO’s method — in my humble opinion — produces an understated number, but I won’t bore you with that.

CASIO’s data is worth looking at, if only to see the trend:

CAISO normally treats transaction price details as confidential.

But a few years back, two professors of computer science at the University of Chicago, Andrew A. Chien and Liuzixuan Lin, were given access to some older CAISO transaction data.

In the time that data covered, Chien and Lin saw curtailment going up 40% a year.

And scant evidence that the commonly discussed ‘solutions’ for curtailment — batteries and exports — were making any dent in that growth rate.

That bit of math, at least, is not complicated.

After the amount solar generated exceeds 100% of what is needed — crosses over my fuzzy line — all additional solar gets curtailed.

Okay, now I’ll make it complicated. The rate of curtailment for solar overall approaches, as to an asymptote, the rate of solar’s growth.

That’s what E3 was talking about in 2014 when it used the word ‘exponential’.

Curtailment also starts to metastasize, showing up at unexpected times and places. A recent new one is summer mornings. Think of a pond overflowing first at the lowest spot on the bank, then in more and more places.

In a January 2024 update of their paper, Chien and Lin guessed that, if the current trend holds up, California might throw away as much as 18.4 TWh of solar-generated electricity in 2028.

That, for scale, is almost equal to California’s current installed solar capacity, 19.85 TWh as of November 2024.

For more scale, California’s in-state actual electricity generation in 2023 was 203 TWh. So throwing away about 10% of that.

Some ideas put forward to take advantage of excess solar, such as green hydrogen, definitely belong in the same idea bucket as corn ethanol.

More transmission will not solve a duck problem.

The duck problem, as they say in animal husbandry, is a feeding problem, not a problem with the fencing of their pen.

As long as the ducks can gorge on surplus solar, they multiply.

More transmission just makes it easier for the ducks to spread around.

Cutting a hole in the hedge so the ducks can get into your neighbors’ yard might help reduce your duck problem.

But then you’ll both have ducks.

In Europe — even among countries not well-integrated on the grid —the duck curve is showing itself to be highly contagious.

There are stirrings of energy nationalism there.

Of which one slogan might become: “Your duck? Your problem.”

To the extent that California’s swamp creatures have a plan, massive overbuilding seems to be it.

The California Air Resources Board says the state needs to add about 10 GW of solar per year.

In a unit I use, that’s five Vogtles.

The California Energy Commission is on the same page: “To provide 100% clean electricity by 2045, California will need to build an unprecedented amount of new utility-scale clean energy.”

The Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) — which, being the trade association, may be over-optimistic — thinks California’s solar capacity will grow 50% in the next five years.

While researching this piece, I started to have a suspicion I was missing something.

Perhaps my thinking had taken a wrong turn.

It happens. I try keep an open mind.

“Recalculating route,” as She would say.

I had started out thinking: Because of the subsidies, California has too much solar.

After a course correction, I now think two things at once:

Because of the subsidies, California has too much utility-scale solar.

California is going to get a lot more rooftop solar + batteries, with or without subsidies.

I failed to see the street sign marking a long-term technology and business trend.

In defense of that wrong turn, my attention was distracted by the grid.

I collect numbers the way some people do Lepidoptera.

CASIO’s numbers for the grid float around in great profusion.

The rare number I should have been looking for was: actual electricity consumption whatever its source.

Energy punditry is so grid-centric.

It doesn’t occur to the pundits that electricity can come from anyplace else.

Or, if it can, that it could be all that important.

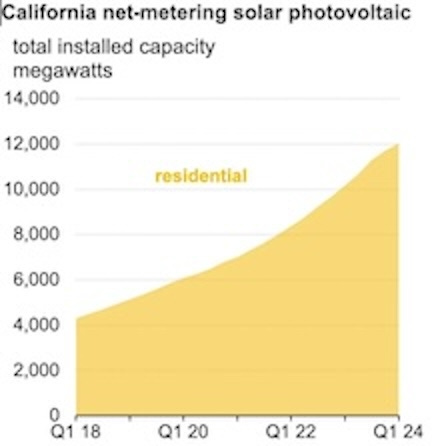

The surprise Lepidoptera factoid for me was: 10% of all electricity actually generated in California comes from rooftop solar.

Aside: By which I mean solar from residences, schools, businesses, and ‘community’ installations, wherever the panels are physically located. In ‘community’ solar, they might be on the ground in lot nearby and shared by an apartment complex. Policy wonks sometimes use a very unenlightening acronym for such ‘distributed energy resources’, DER. I’d prefer to speak English.

That compares to 14% actually generated by large solar farms.

Once I knew what to look for, I caught some other numbers.

About 20% of single-family homes in California, approaching 2 million, have rooftop solar panels.

And, since 2020, California has required newly-constructed homes to come with solar panels installed.

The burdensome paperwork imposed by the utilities on rooftop solar has one backhand benefit: a good statistic.

A ‘net’ meter allows electricity to flow both to and from the public grid. About 99.5% of California solar is net-metered. Here’s that chart:

A new picture of the duck appears in light of California’s all-in electricity demand, not just demand as witnessed on CASIO’s grid.

The duck doesn’t go away. His morning and evening shoulders are still visible in the blue band. But the curve is bridged over:

Aside: The chart, to be sure, comes from the California Solar+Storage Association. But I suspect it’s accurate enough.

Which makes simple common sense to me: In the summer, in California, electricity demand is highest during the day, when shops, schools and offices are open and air conditioning is on. Duh.

CASIO’s grid statistics can get misleading to the point of being dangerous.

For example, the increase in rooftop solar in California shows up in them as a reduction of the state’s electricity demand in the official statistics.

That’s because rooftop solar — ‘duh!’ again — doesn’t get put on the public grid.

Conclusions about the efficacy of energy conservation programs may be getting it all wrong.

The official chart as published by California Energy Commission shows a flatline or even mild downtrend. The webpage with this chart is here.

The flatline always been a bit mysterious. Are all those virtuous conservation programs working? Is the state de-industrializing?

Maybe both, but I think a more obvious answer can be found in a footnote to that chart: “does not include behind-the-meter rooftop solar photovoltaic generation.”

That down trend is the inverse of the up trend in California rooftop solar.

People from outside the state are prone to explaining the behavior of Californians with the clichés of popular psychology.

Those Californians want to be conspicuously virtuous consumers.

Aside: Sometimes called ‘prosumers’.

It’s even hinted that’s why they mount the solar panels on the roof. They want the neighbors to see them.

My prosaic, business-writer explanation is different.

Where others see posers, I see utility customers jumping ship.

To the extent they are able.

Which turns out to be a trend the utilities have seen coming since 2014.

That was the year the Edison Electric Institute (EEI) — which represents the investor-owned utilities nationally — concluded that rooftop solar was a threat to the utility business model, and commenced a lobbying campaign against it.

Denizens of the political swamp are not terribly choosy about their bedfellows.

The EEI turned for assistance to the American Legislative Exchange Council, ALEC, that creature of the Koch brothers.

ALEC specializes in drafting model legislation state legislators can copy-and-paste into law.

Last year, California state legislators, to some surprise, did just that.

In California, that was the result of an unlikely alliance among swamp creatures.

The utilities got an assist from some think-tank nerds, who got the ear of the CPUC and the governor.

Aside: I’m a bit chagrined to admit the many of the think-tank nerds inhabit the U.C. Berkeley Haas School of Business.

Now, it’s possible to feel sorry for think-tank nerds.

There’s a syndrome common among energy pundits I call central planning envy.

Lenin’s 1902 book was called What Is to Be Done?

The pundits love to weigh in on that question. It’s always fun to opine about what you would do if you were the boss of things.

The unmistakable sign appears in speech: all those sentences that begin with ‘What we need to do is…’ or ‘We should…’ .

In a different world, the pundits would have good jobs in the department doing ‘integrated resource planning’ at a state-owned utility monopoly, as in Europe.

Or even in one the California utility monopolies prior to deregulation. In 1996, the nerds were told to pack their slide rules, take their Eversharp pencils, and go home.

The market had it from there.

The economist nerds, of course, would favor utility-scale solar over rooftop. The cost to generate electricity per kilowatt is less. Thus if you were building the state-owned power system from scratch, it would be the economically ‘efficient’ choice.

Sadly, the wonks have to settle for an ersatz, indirect version of central planning.

They can’t dictate the actual hardware to be used in the power system. All they can do is recommend tweaks to the market.

At least the market becomes an endlessly fascinating science experiment for them.

Complete with lab rats, otherwise known as California ratepayers.

The wonks must work out incentives to get the rats to Do the Right Thing.

Which the wonks are confident they know, but the rats might not.

The rats can get a bit confused about the Right Thing.

They need to use less electricity, but still go out and buy electric cooktops, heat pumps, and EVs.

The first lesson the rats need to learn is: they’re just going to have to conform their schedule to that of the duck.

Rats need to do laundry at noon. And make sure the dishwasher finishes up before 4 p.m.

Aside: Since mid-day dinner was once the big meal of the day, the right food pellet incentive might get them to go back to that.

And the rats need to understand the deep shame of coming home from work and turning on a flat-screen TV at 6:30 p.m. Don’t they realize that’s when the sun is going down?

Earnest policy debates revolve around issues like: How many Time Of Use (TOU) periods to have? Are three better than two?

Of course there’s got to be ‘critical peak pricing’, CPP. But maybe be nice about it and offer ‘peak time rebates’, or PTRs.

All of which makes choosing a utility rate plan about as baffling as buying an airline ticket.

I know it’s unthinkable, but try to perform a thought experiment in which there’s an all-nuclear grid.

None of that time-of-day stuff, or seasonal stuff, would matter.

The rate plan would something like: the more you use, the more you pay.

Or even — as is true for rooftop solar owners in the afternoon — use as much as you like. There’s plenty.

What a concept.

Aside: I’ve experienced a version of this in the real world, if you consider France to be the real world. My French friends were quite proud of the nuclear plants. For them, worrying about switching the lights off all the time was a behavioral quirk to be tolerated in foreigners, who were known to be a little weird.

The think-tank wonks have made other contributions the utilities’ bottom line, not just by assisting the marketing department sell heat pumps and EVs.

One think tank notion, quickly taken up by the utility lobby, is that there is a ‘solar tax’ being paid by non-rooftop solar owners.

Which the utilities might as well pocket.

The think-tank wonks understand how to appeal to California liberal sensibilities. They spun this as an ‘equity’ issue.

Rooftop solar owners aren’t, according to their calculations, paying their ‘fair share’.

Of something. It’s not entirely clear what.

Anyway, a reverse Robin Hood thing seems to be going on. Those affluent rooftop solar owners are stealing from the poor to give to the rich. They’re parasites.

The title of a 2018 Haas blog post gives the idea: “Why Am I Paying $65 a Year for Your Solar Panels?”

The $65 came by totaling what the utilities spend on things that, in the wonks’ wisdom, are good things, including carbon costs and maintaining the transmission lines, and dividing by the number of customers. That was the ‘fair share’.

‘We’ all need to chip in and do our bit.

All sounds very egalitarian.

It was something like a ‘Go Fund Me’ for the utilities.

Thing is, California’s ratepayers have already given very generously to that one.

The wildfires, starting with the Camp Fire in 2016, were one of those tons-of-media issues that inspire California politicians to get out and do something about it.

Although I suspect not many joined CalFire crews on the ground. Or in the air, by helping dump fire retardant.

The legislature sees its job as throwing a large pot of money at the problem.

Normally, a state passes a bond issue to deal with a huge, multi-year infrastructure project, such as burying power lines.

In California, no.

It’s now on the utilities, which means on their ratepayers, at about $5 billion per year.

Wildfire mitigation costs are, last I looked, 13% of the typical California electric bill.

I’ve got nothing against wildfire mitigation.

But it’s like buying insurance. It’s very difficult to decide how much you really need.

The utilities — and their labor unions — have been happy to sell the state a whole lot of it.

Since the ratepayers will end up covering the cost, there’s no burning incentive to see it done cost-effectively.

Doing it cheaper might involve such things as just putting covers over the existing lines, to prevent them coming into contact with trees or other vegetation, as opposed to digging trenches to bury them.

Or maybe there’s something that’s out-the-box innovative, such as helping CalFire put up a rapid-response drone fleet to patrol the transmission lines. A private pilot called in one fire just as it starting after seeing a big blue flash from the air.

Not all of the money is going to backhoe operators burying power lines in fire-prone areas.

The big three utilities have also paid $10.5 billion into a wildfire insurance fund.

I won’t come right out and call it one, but the wildfire insurance fund comes pre-packaged with plenty of boondoggle potential.

That’s thanks in part to a singular quirk in California liability law.

In most states, when a government agency takes a right-of-way by eminent domain (paying whatever compensation eventually gets haggled out), owners of nearby property can’t claim the agency damaged their property.

Eminent domain always has a mean aspect, but it’s supposedly for the greater good. As a practical matter, you have to draw a line somewhere.

Not so in California. A 1990s court decision opened the way for property owners to sue a utility even if they live beaucoup miles away from the power line.

That means PG&E was, legally, on the hook for the wildfire damage to any and all of those vast acres reported in the news.

PG&E’s most recent bankruptcy filing was one inevitable result.

Aside: Both of PG&E’s bankruptcies raised an interesting question: maybe the state of California should just buy/takeover/nationalize the blasted company. That’s a tough one.

Some of the ratepayer billions are going to the trial lawyers, who represent claimants who lost houses in fire-prone areas, who want compensation so they can rebuild their houses in those fire-prone areas.

The Haas calculations about ‘equity’ also neglected a surprising — to me — factoid: 30% of California utility customers get ‘low-income’ assistance.

California’s official poverty rate, as calculated by the Census Bureau for 2021-23, was 11.7%.

The low-income programs have acronyms like CARE (California Alternate Rates for Energy), REACH (Relief for Energy Assistance through Community Help), and FERA (Family Electric Rate Assistance).

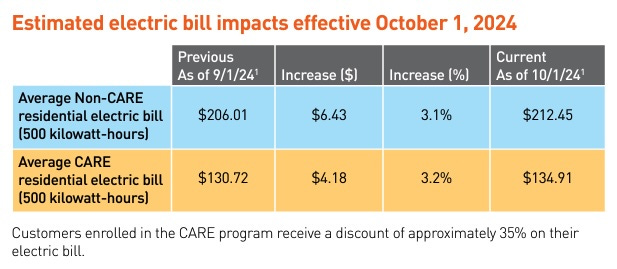

CARE is a pretty generous program:

California is an expensive state.

When I’m there, I feel my dollars were converted to Italian lire or something when I crossed the state line.

In June, I paid $98 for four beers at Dodger Stadium. Before tip.

Aside: Woody Allen’s great line: “We grew up so poor we had to steal to eat. Then we had to go out and steal again. To tip.”

I’ve got nothing against helping the poor. But how you do it matters.

A household of 1 or 2 qualifies as ‘low income’ for CARE it they make less than $40,880 a year.

The money for the low-income subsidy is collected from those ‘other’ utility ratepayers.

So the ‘equity’ debate is going on in a two-class, or two-tier system.

For utility ratepayers caught in the middle, those just above the line, the CARE-type fees definitely work out to be a regressive tax.

Most anyone in public policy will tell you that transfer payments, aka welfare, ought be paid out of the income tax, which at least tries to be progressive.

But California state politicians really don’t like having to go on the record and vote for higher taxes.

It’s much less risky, politically, to put the costs of social programs on utility ratepayers.

The generosity of these programs tends to creep up, until some other politician comes along and gets elected by promising to whack them back.

California is a notoriously high-tax state, but people sometimes forget it’s also the state that elected Ronald Reagan governor in 1967 and passed Proposition 13, the infamous property-tax freeze, in 1978.

The politics of the high-utility-rate issue, I think, feature the same sort of simmering dissatisfaction — or disgust — that boiled over in tax revolt of olden days.

But technology may be those disgusted utility ratepayers another option.

They’ll be able to vote with their feet.

The ‘solar tax’ issue comes down to the utilities insisting rooftop solar owners share the pain of the duck.

The original net-metering tariffs went back to early days.

Importantly, before the duck was hatched.

The tariffs were designed to get rooftop solar solar off the ground.

They were generous, to be sure. But not crazy.

Under the old tariff, a rooftop solar owner could sell electricity to the utility for maybe 20¢/kWh at any time.

That figure was based on a guesstimate of what costs the utilities were ‘avoiding’ by not having to build additional generation and transmission for those customers. It’s a very hard calculation to make.

As a reality check, the number was in the ballpark, maybe a little less, of what the customer was paying per kilowatt hour.

Under the new tariff, which went into effect in April 2023, rooftop solar owners get the wholesale price at the time interval.

Which is at best maybe 4 or 5 cents per kilowatt during daylight hours.

Percentage-wise, it was a sudden draconian cut of about 75%.

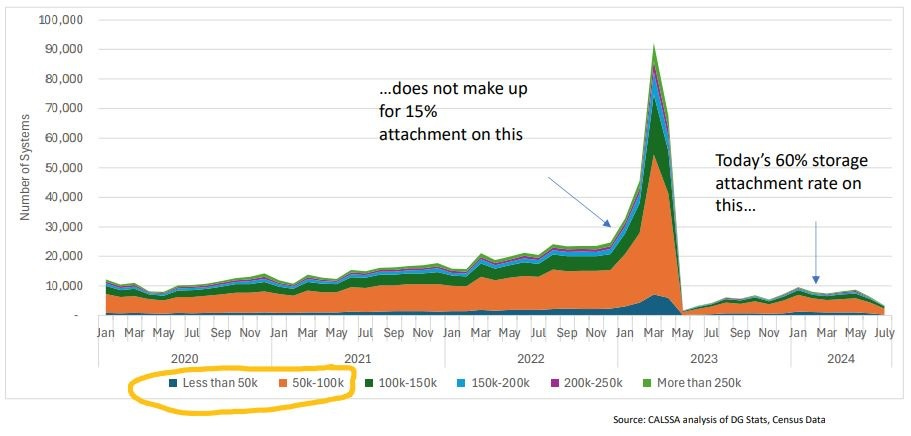

Not surprisingly, the new tariff put a big hit on the rooftop solar installation business.

Which employs many thousands in the state. So much for those green jobs.

It’s a little too soon to tell the long-term impact. There was a big rush to get grandfathered-in before the new tariff took effect.

One consequence is already clear: rooftop solar owners are now buying a lot of batteries. What’s called the ‘storage attachment rate’ is up to around 60%:

Like it or not, rooftop solar owners will have to get into the time-arbitrage game played by the big boys.

A related CPUC edict also reduced commercial net-metering rates.

Which affected not just small businesses — for whom rooftop solar is vital in keeping the air conditioning on in hot parts the state — but also schools. After staff salaries, energy costs are the second-biggest expense of most school districts.

The ‘solar tax’ argument spun so well the utilities used the same argument to add a fee on non-rooftop solar owners.

On May 9, 2024, the CPUC approved the utilities charging a flat fee on everyone who connects to the grid, the fixed monthly fee being $24.15 for most customers.

At those things will be good for utility profits in the short term.

But the utilities seem blind to what’s coming.

And could learn a lesson by looking at the past, specifically revisiting some of the issues that came up in the deregulation debate of the 1990s.

It was not written in stone that deregulation had to do away with vertical integration.

A road — not taken — would have been to allow different vertically-integrated entities to compete among each other, in the monopoly utility’s previously exclusive territory.

Virtual power plants, VPPs, are a new fashion that seem to be rediscovering of the virtues, on a local basis, of vertical integration.

But I think the issue of the 1990s that will come back to haunt the utilities is ‘retail choice’.

Retail choice sometimes doesn’t matter much. Mobile phone providers are all selling more or less the same thing.

But rooftop solar owners want to buy a different class of thing than what’s on offer from the utilities.

They do still have to buy some electricity, so utilities can pretend that’s what they want.

But what rooftop solar owners really want to buy is better thought of as an insurance policy, not electricity.

No rooftop solar owner — at present — thinks their system, even one with a good-size battery, can run everything in their house all the time in every season.

But the utilities’ business model, as the Silicon Valley cliché goes, is just a few steps away from ‘disruption’.

It would only take one entrepreneur to come up with a cheap, all-day, whole-house battery to kick off utility cord-cutting in earnest.

The idea of the going without electricity supplied by a utility may sound improbable.

But not too many years ago everyone had to have a land telephone line.

Paradoxically, the politicians, by forcing the utilities to put all their eggs in the renewables basket, are not doing them any favors.

The mandates are busy eliminating the one thing that would give the future grid some real utility. That would be a grid that’s not erratic, undependable, and prone to price wild swings.

I suspect that by 2045, when California goes Full Monty on renewables, most utility customers will have gone full Ted Kaczynski. They’ll be off the grid.

There are other signs of a trend to ‘grid defection’.

The recent round of data center announcements have one thing in common: none of the companies making them are looking to the public grid for be their solution.

When grid defection happens at sufficient scale, the legacy of today’s politicians, a limping public grid, will go the way of public transportation.

Those who can afford it will have a private option.

Everybody else will get to take the bus.

We see the a similar dynamic at work in private versus public schools, and health care.

I’m not endorsing this two-class outcome. I just see it coming.

In California, questioning the urgency of the Net Zero Transition gets you branded a heretic.

And there’s the omertà under which the centrality of natural gas in real-world electricity generation is not be mentioned.

Don’t say its name and maybe it will just go away.

As for believing, as I do, that CO₂ is not a ‘pollutant’… Heaven help the benighted.

That’s probably why I keep my mouth shut when I’m out there.

For my next road trip, the iPhone app I want is called: “Is This Thing On?”

That brainstorm came to me driving east on I-580, departing the Bay area, while going through Altamont Pass.

I can tell if something is growing in a corn field, or if the farmer is leaving it fallow.

Altamont Pass has some of the original wind turbines put up in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Their blades turn once in a while, but they don’t seem to be doing much.

And whizzing past those solar panels in the Mojave, you also have no way of knowing what they’re up to.

Are they on? Has the owner switched them off because CASIO asked him, to or because the price of electricity is negative?

You don’t really know.

If my Fitbit can detect when my cold heart beats, some tech gizmo ought to be able to sense when electricity juices are flowing.

And those old Altamont Pass wind turbines at least deserve an historic marker.

I’d volunteer to draft some text.

My first thought was some variant on an alluring alliterative: “monument to malinvestment” or some such.

But my second thought was to keep it short and polite.

So maybe: “Seemed like a good idea at the time.”

Which it wasn’t.

And neither is all the solar.

I know this post is long.

So in more ways than one, allow me to say: “Enough, already!”