Last Friday, I posted some thoughts in reaction to the verdict in the Michael Mann v. Mark Steyn trial. That post is here.

In case you’re reading this in the future, Friday was 9 February 2024.

The jury's decision came in around 4:30 p.m. Eastern time on Thursday.

In the first hours, many of us who followed the trial were trying to get our head around the jury's $1 million punitive damage award against Steyn.

Over the weekend, there was some time for reflection. And the welcome distraction of the Super Bowl.

So today felt like the right day to do some Monday morning quarterbacking.

Could Steyn's defense — not to be confused with the Chief's or 49er's — have been better, or different?

My first thought when I heard the $1 million verdict was: 'DC jury'.

I’m sure I wasn’t alone in that.

Over the weekend, I had time to do a little online legal venue-shopping.

If you're looking for venue where your skeptical views on climate will get a sympathetic hearing, don’t go to trial in: California, Hawaii, or the District of Columbia.

As suspected, if you had to defend two right-wing bloggers on a climate issue, you could hardly pick a less favorable jurisdiction than Washington, D.C.

'Right-wing bloggers', by the way, is not my phrase. That’s from a headline about Simberg and Steyn in the jury's hometown newspaper, the Washington Post.

Aside: The Washington, D.C. thing can be confusing. In the US, defamation is a matter of state law. The case was heard in the District’s capacity as a quasi-state.

DC is definitely not right-wing territory, unless you happen to be in the House of Representatives. The District voted 86.75% for Biden in 2020. It went almost exactly the same for Hillary Clinton in 2016.

Widening the search from politics to climate, I looked at polls conducted by NBC News and Pew Research.

The top three? If you're looking for venue where your skeptical views on climate will get a sympathetic hearing, don’t go to trial in: California, Hawaii, or the District of Columbia.

I like factoids that come in threes, so I looked up EV sales as a percent of new car sales. DC ranked second to California in 2023.

By Saturday, other writers whose opinions I respect had weighed in on the verdict.

The defense won on merits, and Mann won on the framing and the politics.

Roger Pielke, Jr., who testified as a witness at the trial, attributed Steyn's loss to the prosecution's ability to frame the case as one of ‘climate deniers versus climate science’.

"For the jury," Pielke wrote on his Substack, "this set up the notion that this trial was not really about Mann, but about attacks on all of climate science from climate deniers."

Pielke went on to conclude: "The defense won on merits, and Mann won on the framing and the politics."1

I don't disagree with Roger, but I will add one thing.

I took a moment to look at the list of Simberg/Steyn statements listed as defamatory in the original complaint.

I compared those to the ones the jury actually found defamatory.

All save one involved the Jerry Sandusky 'child molester' business.

Now, it's possible the jury didn't 'get' the nuance, that the analog was to the inadequate Penn State investigations, and so on.

But I think it's more likely the jury didn't care. If 'child molester' appeared in the word cloud, the comment was over the line.

The jury was sending a million dollar message about decorum on the internet.

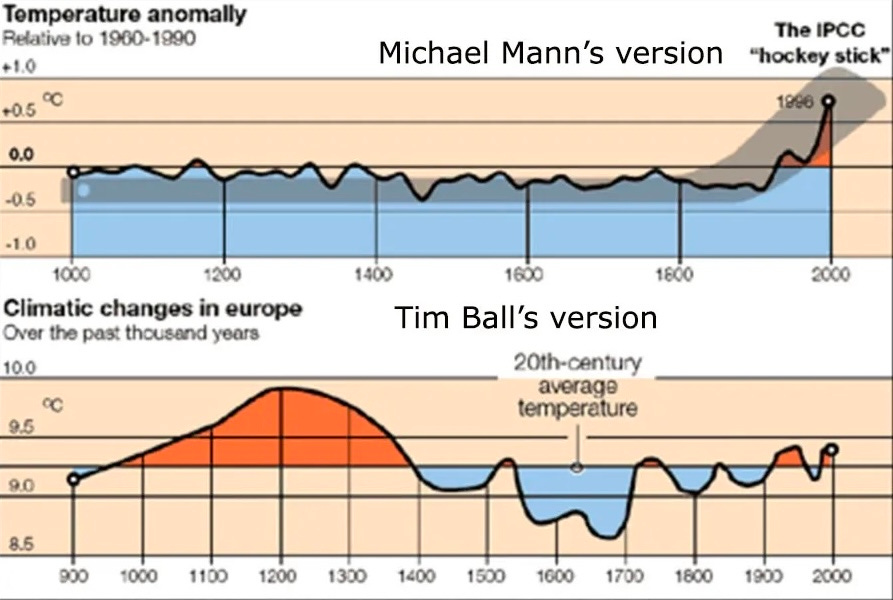

The single science-related statement the jury found defamatory was Steyn's line 'fraudulent climate change hockey stick graph'.

A good Monday morning quarterback will tell you that you should always go with your strongest defense, whether zone or man-to-man.

If the alleged defamatory statement turns out to be true, that’s an absolute defense.

What often gets lost in discussing this case is that Steyn did not have to prove that climate change hockey stick graph was ‘fraudulent’.

It's important to get the turns in the legal dance correct, and the directions of burden of proof.

The first step: Mann's lawyers try to show that Steyn called the Hockey Stick graph ‘fraudulent’ knowing that the Hockey Stick graph was not fraudulent.

Or recklessly not caring whether it was or wasn’t.

In step two, Steyn’s rebuttal, he needed only demonstrate that he had looked into the Hockey Stick and had straight-faced, non-malicious reasons to call it ‘fraudulent’ — allowing for some rhetorical hyperbole.

In 2012, Steyn had certainly looked into the Hockey Stick.

In 2015, he put out a book about it.

“A Disgrace to the Profession”2 should have been defense Exhibit A, with a complimentary copy, signed by the author, handed out to each member of the jury.

In that book, Steyn collected and entertainingly annotated a broad smorgasbord of statements from some 120 scientists, nearly all of whom have doctoral degrees in fields related to climatology.

What is particularly effective about the collection is that the scientists come from all sides of the debate over anthropogenic climate change.

It's a devastating peek into a science that is permeated by considerations of orthodoxy. Highly recommended.

Friday, I said the case never should have come to trial on First Amendment grounds.

I stand by that.

In early days, climate science got a free pass on ‘integrity, accessibility, and stewardship of research data’.

But in reflecting about legal strategy, I think the First Amendment stuff may have inadvertently knee-capped Simberg's and Steyn’s defense as individuals — as opposed to that of the publishers, the Competitive Enterprise Institute (Simberg) and National Review (Steyn). The publishers won a judgement to dismiss in 2021.

This line of argument takes some setting up. I’ll try to keep it short.

Consider the "Policy on Data" of the British Royal Society’s publishing arm:

As a condition of acceptance authors agree to honour any reasonable request by other researchers for materials, methods, or data necessary to verify the conclusion of the article… Supplementary data up to 10 Mb is placed on the Society’s website free of charge and is publicly accessible. Large datasets must be deposited in a recognised public domain database by the author prior to submission. The accession number should be provided for inclusion in the published article.3

A number of scientific journals, especially biomedical and econometric, similarly insist that authors lodge both data and computer code with the journal before publication.

If they refuse, the paper isn’t published.

The US National Academies Press has a 178-page book that earnestly ponders these issues: Ensuring the Integrity, Accessibility, and Stewardship of Research Data in the Digital Age.4 Its focus mainly on integrity in medical research.

In early days, climate science got a free pass on ‘integrity, accessibility, and stewardship of research data’.

Today, we’ve got lobbyists coming to us and saying that, based on ‘the science’, we need to give the Industrial Revolution a do-over.

Only umpteen trillion. Either that, or maybe just ditch the industrial economy altogether.

A concerned taxpayer might want to go back and re-check the calculations.

Many of the 'attacks' on scientists so bemoaned by NPR, the New York Times and the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund are in the class of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests.

Certainly, FOIs can be abused; politically motivated; or a nuisance.

Yet the more defensive climate scientists seem to have an abnormal interest in not letting anyone see how the sausage got made.

Or, stranger still, claiming their earth-shattering results are ‘proprietary’.

Which is doubly odd, considering the taxpayers most likely paid for it, one way or another.

Which is a long-winded introduction to a point about the legal defense: for a would-be plaintiff of defamation, the usual deterrent — the big bomb — is that it opens up discovery.

In a no-holds-barred legal case, an aggressive defense attorney will hit the plaintiff with a massive discovery request the minute the ink is dry on the complaint.

As defendants, Steyn and Simberg had a perfect legal right to go fish for anything that might help them make their case that Hockey Stick was known to be a bit dubious.

Emails, intermediate computer results, whatever, going as far back as, say, 1997.

Those discovery requests could have been served not just on Mann, but on his co-authors, colleagues in East Anglia, the journal Nature, the IPCC, etc.

Litigation over discovery would have become the case.

Now, SLAPPs are Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation. Most US states have anti-SLAPP laws.

These can allow a judge, after some informal fact-finding, to toss out a case if he or she decides the real reason the plaintiff sued is to shut the defendant up and, on First Amendment grounds, the defendant should not be shut up.

The goal is not to let well-financed plaintiffs chill or punish protected speech just by running up the legal tab of their target.

Publishers and internet sites like anti-SLAPP laws.

The problem with relying on a SLAPP defense is that filing an anti-SLAPP motion puts discovery, which is expensive, on hold.

By the time the SLAPP motion gets resolved, the wind can be out of the sails.

If the ‘discovery’ defense sounds far-fetched, it worked for the late Dr. Tim Ball in Canada. Ball died in September 2022.

In February 2011, Ball joked to an interviewer that Mann “belongs in the state pen, not Penn State.”

The interviewer wrote that up and put it on the website of an outfit called the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Mann's Canadian lawyers sued both.

Ball, who had a PhD in geography and was a specialist in historical climatology, essentially said bring it on.

In discovery, Ball demanded any R² numbers calculated by Mann in the course of his work. In statistics, R² is a classic metric for ‘goodness of fit’.

Mann has been extremely evasive about R² for decades. Ball suspected R² might be Mann’s kryptonite.

There is a body of opinion that Mann, in the course of his Hockey Stick research: (1) calculated the R²s; (2) saw they weren’t very good; (3) intentionally decided to downplay (or ‘suppress’ — pick your word) them; and (4) switched to using a different and unconventional metric that made the results look acceptable.

Mann's Canadian attorneys refused to produce the R²s. They argued the numbers were ‘proprietary’.

After years of wrangling with, and stalling by, Mann's lawyers, the Supreme Court of British Columbia lost patience. In 2019, it dismissed Mann’s suit, awarding full legal costs to Ball.

The corruption of climate science can be precisely dated in time and place: October 1995; Madrid, Spain.

That’s when and where the UN put the thumbscrews to the — hitherto — relatively innocent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Australian historian Bernie Lewin describes it best: “After a long struggle, the levees of science gave way to the overwhelming forces of politics welling up around it, and soon it would be totally and irrevocably engulfed.”5

After that, the climate policy cart led the climate science horse.

I observe that 1995 is also a good year to mark the rise of the Internet.

Stay with me on this one.

Traditional legal and academic notions about research duplicity have been hopelessly outgunned by modern technology.

No doubt old-school ‘data falsification’ still happens from time to time.

And, if discovered, it should of course be sanctioned.

But today there is no need to surreptitiously grab the clipboard and write in some fake numbers.

This is because what NPR celebrates as ‘climate scientists’ are not, in the vast majority, field researchers clomping around on glaciers and drilling ice cores.

The few that do that sort of thing get my respect.

The others, the spreadsheet scientists, are better called data analysts.

They work in comfortable (climate-controlled!) offices hard to distinguish from those of say, McKinsey & Co., except that perhaps the expresso machine isn’t as nice.

On the internet, they can find any climate dataset they want. Downloads in seconds! They don’t need to get out their chair, let alone go into the field.

The contributions of the desk-bound climate scientists consists of coming up with clever methods of slicing and dicing old data so it ‘tells a story’.

Preferably a story that a journal — and, with luck, the mainstream media — will find ‘compelling’.

Scary is good. Fiction writers know that too, you know.

In climate science, ‘cherry-picking’ data in the interest of telling a good story is widely practiced, even approved of.

Cherry-picking involves examining data before processing and not using that which might lead to a ‘wrong’ — or boring — answer.

In a presentation to a March 2006 National Academy of Sciences panel looking into the Hockey Stick, tree-ring specialist Rosanne D’Arrigo reportedly put up a PowerPoint slide saying that cherrypicking was necessary “if you want to make cherry pie.”

Consider a trial of new drug in which only the results from a handful of ‘best-responding’ patients are reported.

That would be outright illegal in most parts of the world.

Who is supposed to put the brakes on this stuff?

I think it’s pretty well established that while ‘peer review’ may help, it’s not up to the job.

The peers may be pals, or part of a network with a shared interest in telling the same story.

Nor are peer reviewers expected to do any heavy lifting, such as replicate results.

The corporate world sometimes sets up ‘Red Teams’ to test and contest critical conclusions — such as ‘This software can’t be hacked’ — in a controlled, pre-release adversarial process.

In the Hockey Stick controversy, Stephen McIntyre and Ross McKitrick somehow became the Red Team. They are citizen-science heroes.

If parts of climate science are not to degenerate into pseudo-science and eventually go the way of phrenology or eugenics, it seriously needs to police itself.

The IPCC, a political entity, is, I fear, part of the problem, not the solution.

In my opinion, the IPCC is beyond reform. The rot has set too deep. It should defunded and replaced with something else.

There are a number of good ideas about what an IPCC 2.0 might look like.6

In the meantime, the blogosphere is what we’ve got.

Which includes, indecorous as they may have been, Rand Simberg and Mark Steyn.

“False Equivalence: Making Sense of Michael Mann's Resounding Defamation Victory” on his Substack The Honest Broker, Feb. 8, 2024 (link).

Mark Steyn, “A Disgrace to the Profession” (the quotes are part of the title), 2015.

Quoted in Andrew Montford’s The Hockey Stick Illusion, 2010. Monfford’s link to the Royal Society Publishing site is dead, but I rather doubt the policy has changed.

Lewin is the author of a great 2017 book, Searching for the Catastrophe Signal: The Origins of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change which incorporated material that first appeared on his blog “Enthusiasm, Scepticism and Science'“ subtitle “on the origins and impacts of Global Warming Alarmism in the history and philosophy of science”. The particular blog post about Madrid 1995 is here.

For one example, see “What Is Wrong With the IPCC? Proposals for a radical reform” by the very same Ross McKitrick, Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF), Report 4, 2011. For a less radical suggestions, look at the five essays in Nature, 10 February 2010, published under the headline “IPCC: cherish it, tweak it or scrap it?”.