When my brain works at all, it’s not entirely normal.

I’ve learned to live with it.

In the blizzard of executive orders signed by President Trump on January 21, 2025, one little snowflake riveted my full attention.

Trump ordered the Environmental Protection Agency, the EPA, to reconsider its 2009 ‘Endangerment Finding’ about CO₂ and other greenhouse gases.

Two years ago, in May 2023, the EPA announced rules that called for ‘carbon capture’.

An idea stuck in my brain back then: that before we lock away CO₂ and throw away the key, it deserves a fair trial. Everyone deserves a zealous defense.

CO₂ couldn’t afford an attorney, so we had to find him one.

And CO₂ was not exactly a defense attorney’s dream client. More of a nightmare.

The media had already appointed itself CO₂’s judge, jury and executioner.

And it was in a hanging mood.

They talked about injecting CO₂ underground.

I didn’t know if that was cruel or unusual, but it sounded pretty bad to me.

The media was howling that ‘sequestration’ — even for life — was too good for CO₂.

That was because locking up CO₂ would give those fossil fuel interests a Get Out of Jail Free card.

If law-biding citizens knew CO₂ was going to get put away, they’d breath easier and burn more a lot more natural gas.

So I was the only one dumb enough to take on CO₂’s case.

It was a long trial. You can read my equally long account of it here.

That time we managed to get CO₂ off.

I say ‘we’ to include Miranda, my annoyingly competent office assistant.

By way of an update, Miranda and I are still hoping to get a check from those fossil fuel interests everyone knows about.

With the one anonymous donation we did get, Miranda paid her back salary and the office rent.

All I saw out of it was a triple latte and a banana crunch muffin.

Which wasn’t bad, but after our years together, you’d think she’d know to get blueberry.

Anyway, we kept CO₂ out of the Big House. That time.

But the poor guy has been in the doghouse of public opinion for what? Forty years?

You’d think he ought to get some credit for time served.

Enrique Tarrio, former leader of the Proud Boys, only did two years at the Federal Correctional Institution in Pollock, Louisiana before his sentence was commuted by President Trump.

And CO₂ hasn’t even been pardoned. He’s only been declared eligible for rehab.

Or — to use the fashionable word — he has a ‘pathway’ to rehabilitation.

But in a fee-starved and ethically-challenged legal practice such as my own, appearing before parole boards comes with the territory.

As I often say to Miranda on slow mornings: “Today we need focus on being of excellent service to our incarcerated clients.”

I’ve practiced rolling my eyes the way she does in a mirror.

I can’t quite get it right.

Sometimes I think it has to do with my eyebrows.

Maybe I should ask her to pluck mine so they’re exactly like hers.

But that might not be appropriate.

Also I’m afraid it might hurt.

“Miranda?” I say.

“Yes, Boss?”

I like it when she calls me that. Even when she’s just being sarcastic.

“Do you think we could put the cactus out on the fire escape?”

When CO₂ was being held two years ago, he asked me to get him a jail cell companion. Miranda’s been taking care of the cactus since CO₂ was released.

She’s grown protective about the spiny thing. I think she’s afraid I’ll knock it over.

“The fire escape?”

“We need to get in touch with CO₂. You know, send him a signal.”

“Like putting a candle in a window?”

“I’m thinking about the cactus.”

“The Pennsylvania Dutch used to put a lighted candle in their windows so runway slaves on the Underground Railroad would know where to find shelter.”

Jesus. A one-woman Wikipedia. “Please?” I ask.

She disappears and reappears with the cactus.

“Are you going to need my help getting the window open?” I ask.

“I can manage.”

She heads for the window.

“Please don’t light the cactus on fire.”

There’s the eye roll.

I start rummaging around for my copy of Legal Defenses for Dummies.

I hear a lot of banging coming from the vicinity of the window.

I studiously ignore it.

I’ve got to work to do on CO₂’s appeal.

I start by finding the text of Trump’s executive order.

At least it’s short:

Within 30 days of the date of this order, the Administrator of the EPA, in collaboration with the heads of any other relevant agencies, shall submit joint recommendations to the Director of OMB on the legality and continuing applicability of the Administrator’s findings, “Endangerment and Cause or Contribute Findings for Greenhouse Gases Under Section 202(a) of the Clean Air Act,” Final Rule, 74 FR 66496 (December 15, 2009).

I have to read it twice.

Okay, maybe three times.

I do know what the “Endangerment and Cause…” and all that is.

That’s the 2009 finding in which the EPA labeled my client a ‘pollutant’ and a ‘danger to public health and welfare’.

I did once discuss with CO₂ the idea of suing the EPA for libel.

But aside from having no money, CO₂ has his other interests. They take a lot of his time.

His big hobby is horticulture. Gardening, whatever. He’s good at it.

I need to find out who this ‘Administrator of the EPA’ is. It looks like he’s the guy who will decide my client’s fate.

A few seconds on Google reveals his name: Lee Zeldin.

He’s a former Congressman from Long Island.

In 2022, he ran for governor of New York and lost to Kathy Hochul.

My grasp of Long Island geography is a little weak. I try to figure out where the town of ‘Shirley’ is.

I look on a map. It’s not far from ‘Yaphank’.

That clears that up.

I scroll down and read some old articles about him: “Senator Lee Zeldin Marches in Lake Ronkonkoma Memorial Day Parade.”

There’s a photo of him at the parade with his twin daughters, Arianna and Mikayla. In the photo, they look to be about ten.

Those politicians. Livin’ the high life.

I turn to read what the political pundits are saying about him now.

Rolling Stone calls him “Fossil Fuel’s Inside Man.”

That’s promising.

But if he expects to get a check out of those fossil fuel interests, I hope he has better luck than I did.

On February 2, 2025, more than 1,100 EPA employees who “work on climate change, reducing air pollution, and enforcing environmental laws” got an email saying they could be fired at any time.

That 1,100 figure sounds suspiciously like it was taken from the old joke about what you call 100 lawyers at the bottom of the sea.

Which relates weirdly to Zeldin’s February 12 announcement that the EPA had recovered $20 billion in gold bars that Biden EPA staffers had tossed overboard at the last minute. Apparently they thought they were onboard the Titanic.

I just hope the Zeldin EPA has sense enough to leave that $20 billion in gold. It’s been going up. If I were the EPA, I wouldn’t trust the U.S. dollar.

I watch Lee Zeldin’s Senate confirmation hearing, all 3½ hours of it.

They don’t dare ask about a nominee’s religion at confirmation hearings these days.

Zeldin is asked by several of the Senators if he believes in climate change.

He says he does.

Senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island appears on the verge of asking him twice. Whitehouse seems to want to say, “But do you believe in Climate Change?”

That’s because you can believe in climate change without Believing in Climate Change.

Whitehouse holds up a scary-looking map of Rhode Island with parts of the coastline colored in bright green.

I like maps. I try to find that one.

The best I can do is this:

That red is probably more scary than bright green.

I try to figure out what it means.

Rhode Island subsided about 6 inches over the last century.

That’s lamentable.

But I’m not sure they can pin that one on my client.

The Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC) says that if there’s a 100-year storm in the next 100 years those red areas are going to get soaked.

“What are the odds on that?” I scoff.

I read on.

In 2019, Grover Fugate, executive director of the CRMC, told a gathering of Newport, Rhode Island realtors: “This will transform the real estate market.”

I make a note on my desk blotter: “Find a realtor who knows about beachfront property in the Berkshires.”

Senator Whitehouse is convinced sea level rise is all CO₂’s fault.

As is the recent weather. And the Los Angeles fires.

Senator Edward Markey of Massachusetts waxes eloquent about the L.A. fires. “The EPA,” he admonishes Zeldin, “is responsible to keep the fiery embers of climate change under control.”

Nominee Zeldin got through his confirmation hearing.

Which was better than I did. I nodded off around the 2 hour 45 minute mark.

On January 29, Zeldin’s nomination was confirmed by the Senate.

So he’s now the Administrator of the EPA.

I can’t say I envy him the job.

In the UK, the civil service bureaucracy is called The Blob.

It’s hard to imagine leading a blob and having it follow you anywhere.

In the movie, The Blob had a mind of its own. It went wherever it wanted. I can still see it oozing through those ventilator ducts in the movie theater.

The EPA was genetically engineered for Blob-like expansion by its creators in 1970. Nothing has been able to prevent it from expanding.

At least in the movie they figured out they could freeze The Blob. They airlifted it and dropped it in the Arctic Ocean.

So if global warming continues you know there’s going to be a sequel.

In the late 1960s, environmentalists blamed their frustrations on the way federal regulatory agencies were set up.

Most agencies combined several functions. The Department of Agriculture, for example, would advise farmers about how to use pesticides while at the same time being in charge of pesticide safety.

The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was in charge of both promoting the use of nuclear power, and regulating its safety.

So in an 1970s environmentalist victory of some sort, the AEC got split in two.

The ‘promote nuclear power’ part wound up in the Department of Energy.

The ‘regulate nuclear power’ part went to a new entity, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC).

That had what most writers would call ‘unintended consequences’.

Except they weren’t unintended.

Those independent regulators lost touch with the real-world industries they were supposed to be regulating.

Over time, the NRC regulated nuclear power into near-oblivion.

The EPA was designed to be a single-minded ‘advocacy’ agency from the get-go.

Nixon’s advisors told him in 1970 that an advocacy-only EPA was a bad idea.

But Earth Day was coming up on April 22, 1970, and Nixon wanted to look groovy for the nation’s youth.

I’ve often wondered if there is any data available on the length of Nixon’s sideburns in those years.

Here’s Nixon meeting Elvis in December 1970, the same month the EPA was created:

Nixon assumed he’d be running for re-election in 1972 against Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine. Muskie had introduced the first Clean Air Act in 1963.

In case you’ve stopped to wonder, Nixon ended up running against George McGovern in 1972.

One theory behind making the EPA a single-minded advocacy agency was to avoid ‘regulatory capture’.

The industries enjoying those environmental ‘externalities’ economists talked about could afford to hire their own lobbyists. So the theory was to create a countervailing force.

The EPA promptly got captured by the then-new environmental NGOs.

The National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) was founded in 1970.

There was — and still is — a revolving door between the NRDC and the EPA.

For one example, David Hawkins started as an NRDC lawyer in 1971. In 1977, he moved effortlessly over to being Assistant Administrator for Air, Noise, and Radiation at the EPA. Then he went back to the NRDC in 1981.

Gina McCarthy was head of the EPA from 2013 to 2017. In 2020, she became president and CEO of — you guessed it — the NRDC.

As CO₂’s defense attorney, I of course want the new EPA Administrator to recommend to the Director of the Office of Management Budget that the 2009 Endangerment Finding no longer has ‘continuing applicability’.

That’s a mouthful.

Actually, as CO₂’s defense attorney, I want more.

I want an apology.

It may save face for the EPA to say the 2009 Finding about CO₂ ‘no longer applies’.

But that implies it ever did.

The bad things the EPA said about CO₂ in 2009 weren’t true then, either.

And the EPA had bothered to look at some evidence, it would have known it. CO₂ should have been let off the hook.

But you can’t always get what you want. I try to take ‘Yes’ for an answer.

If Administrator Zeldin recommends ending the Endangerment Finding, everybody will say it’s ‘just politics’.

That will be true.

But it was just politics the first time.

We don’t normally ask what was on the lynch mob’s mind.

If you’re in the crowd the next morning watching the body gently swing back and forth on the rope, you don’t tisk-tisk and say to the person next to you, “What were they thinking?”

I hope I can convince the parole board to step into the Wayback Machine.

That’s the only way they’ll understand the weird psychology of 2006-2009.

Global warming hysteria reached a high-water mark during those years.

Starting with Time magazine’s cover from August 3, 2006:

Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth” had opened on May 24, 2006.

Gore had said the Earth would pass the Point of No Return in 10 years.

On July 13, 2006, James Hansen reviewed An Inconvenient Truth — the movie and the book of the movie — for The New York Review of Books.

Hansen wrote that if annual emissions of CO₂ and other human GHGs continued to increase at their then-current rate for another 50 years, sea level was going rise 80 feet.

Hansen got pretty worked up about that:

Eighty feet! In that case, the United States would lose most East Coast cities: Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington and Miami; indeed practically the entire state of Florida would be under water. Fifty million people in the US live below that sea level.

Massachusetts was then suing the EPA in Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency because Boston going to sink into the ocean. Someday.

I went into that case two years ago. But to recap, Massachusetts said Boston sinking into the sea was all CO₂’s fault.

Or would be, when it happened.

Oral arguments in Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency took place before the Supreme Court on November 29, 2006.

The question the Court had to answer was whether the Clear Air Act gave the EPA the legal authority to regulate CO₂.

That Clear Air Act had been passed back in 1970 to deal with actual air pollutants, such as smog from automobile exhaust and sulfur dioxide from burning coal.

For the actual air pollutants that inspired the 1970 Clean Air Act, the EPA could have declared Mission Accomplished around 1992.

They were down and going steadily down.

The EPA could have fired half its Air Office staff and gone into some kind of monitoring and maintenance mode.

So for the EPA was to continue Blob-like expansion, it needed to discover some new bogeymen.

That’s where my client, CO₂, came in. If your job is to get CO₂ out of the atmosphere, you’re guaranteed lifetime employment.

In the 1990s, the EPA had discovered another great bogeyman, PM2.5, fine particulate matter, and that had worked out well for it.

For regulators looking something for to regulate, PM2.5 was a gift from God.

Almost literally. If you consider smoke from wildfires to be natural, natural PM2.5 exceeds that of the anthropogenic kind.

PM2.5, like CO₂, was invisible and all around us.

So it was an excellent scary thing for journalists to write about. They’re very good at playing on people’s phobias about impurities.

I’ll get to PM2.5 below.

Applying the 1970 Clean Air Act to CO₂ in 2006 was an innovative legal stretch.

CCO₂ doesn’t make the air ‘impure’ or ‘unclean’.

So it doesn’t fit the dictionary definition of a pollutant.

You can see through CO₂. So it doesn’t reduce visibility.

CO₂ doesn’t pose a risk to health.

It’s not even an irritant.

You’d really have to work hard to kill yourself with CO₂. People walk in and out of greenhouses all the time where CO₂ is kept at two or three times its level in outside air.

And, as I must point out as CO₂’s attorney, CO₂ was on the planet first.

CO₂ was spread out all over the land several billion years before H. sapiens showed up.

So he’s indigenous, or something like that. That should have given him some bonus points.

But the Supreme Court said, 5 to 4, that the EPA could regulate CO₂.

That decision, published on April 2, 2007, was really about the hazy language Congress used when it wrote the Clean Air Act.

The Supreme Court did not itself say CO₂ was a pollutant.

It said the EPA could say that.

If the EPA studied the matter and, in its considered judgement, concluded that it was.

As for the Supreme Court’s part in all this: we all mistakes.

The justices are creatures of their times.

Which explains some of the staggeringly bad legal decisions they’ve made in American history.

In Dred Scott v. Sandford, the Court ruled that Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent. That was in 1857.

In Buck v. Bell, the Court endorsed eugenics, allowing compulsory sterilization of the ‘unfit’, including the mentally disabled. That was in 1927.1

After the Supreme Court decision, the George W. Bush EPA knew it had the power to regulate CO₂

The Bush EPA approached that power very cautiously.

In July 2008, in what now sounds prescient, the Bush EPA wrote:

the potential regulation of greenhouse gases under any portion of the CAA could result in an unprecedented expansion of EPA authority that would have profound effect on virtually every sector of the economy and touch every household in this land.

All of which happened: the ‘unprecedented expansion of EPA authority’ and the ‘profound effect’ on virtually every sector of the economy.

The EPA has taken charge of U.S. industrial policy, something you might think Congress should want to deal with. It tells the automakers what kind of cars to make.

If the EPA got up on the wrong side of the bed one morning, it could do some damn fool thing with respect to electricity that would snuff A.I. in the cradle.

In February 2007, Al Gore got an Academy Award for An Inconvenient Truth.

Throughout that year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC, put out its fourth Assessment Report, AR4, in big fat installments.

Fortunately those came with their own Cliffs Notes, the Summary for Policymakers. The Summaries came out a month before the fat parts.

The Summaries had the high points of gloom and doom underlined so busy people could skim and get the gist. They were all anybody, especially the press, actually read.

In October 2007, the Norwegian Nobel Committee — the one that gives out the misnamed Peace Prize, not to be confused with the Swedish science prizes — awarded one jointly to Al Gore and the IPCC.

The media was keeping up the scary drumbeat all this time.

In October 2007, for one example, the Associated Press quoted scientists saying “global warming has passed an ominous tipping point.” They predicted arctic sea ice would be gone in five years.

Al Gore liked that one, repeating it on German television in 2008.

Since the hysteria that forced my client to go into hiding was worldwide, it’s worth looking at what the rest of the world was saying about him.

These were collected from Le Monde by French writer Drieu Godefridi:2

2006: “Massive extinction of species expected in the 21st century”

2007: “By 2050, the world could see over one billion climate refugees”

10 December 2007: “Global warming could spark a worldwide civil war”

13 January 2008: “Desertification could affect 2 to 3 billion people”

26 August 2008: We have only “seven years to act.” And, we are headed straight for “a sixth extinction.” Both quotes from the late Rajendra Pachauri, then head of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC.

Then we come to 2008, an election year in the U.S.

The global warming debate stayed heated, even if the real world did not.

For 2008, the average temperature of the lower 48 U.S. states was the coldest it had been in 10 years, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). The 2008 average was 0.1° C. above the mean for the entire 20th century (1901-2000).

In 2008, it was Manhattan, not Rhode Island or Massachusetts, that was headed underwater.

This clip from was shown by ABC on Good Morning America on June 12, 2008, from a special later aired as Earth 2100. That’s a slimmed-down New York City in 2015:

Hurricane Sandy happened in 2012, so maybe they were onto something.

But Sandy’s waters, not to get too Biblical about things, did recede.

Barack Obama promised two big things in his 2008 campaign.

One was to reform health care. We remember that one: Obamacare.

The other one didn’t pass, so we’ve forgotten about it.

It was a huge cap-and-trade scheme for carbon emissions.

After he won the election, Obama told the New York Times on Nov. 18, 2008 that he wanted to move fast on his campaign pledge to reduce “climate-altering carbon dioxide emissions by 80 percent by 2050.”

“Delay is no longer an option,” Obama added.

Policy wonks argue about whether cap-and-trade schemes are a ‘tax’, or what.

They are.

Obama’s cap-and-trade scheme for CO₂ emissions would have cost Americans an estimated $300 billion every year.

Obama didn’t really disagree. During his campaign, he said that under his plan electricity prices would of necessity “skyrocket.”

And Obama made no secret that his cap-and-trade plan would bring about the end of coal-fired electricity generation: “If somebody wants to build a coal-fired plant they can. It’s just that it will bankrupt them.”

On to 2009.

In July 2009, King Charles — formerly known as Prince — gave humanity “96 months to save world.”

In October 2009, Gordon Brown, then Prime Minister of the UK, said we had “Fifty Days to Save Planet from Catastrophe.”

The Obama EPA arrived just in time. On January 23, 2009, Obama's pick, Lisa P. Jackson, was sworn in as the new EPA administrator.

According to internal EPA memos later disclosed to a House Committee, Administrator Jackson wanted an EPA Endangerment Finding on CO₂ to be a done deal by mid-April 2009.

So three months, give or take.

Normally, a decision of that magnitude would get years of study at the EPA. So ‘fast tracked’ is hardly the word for it.

An EPA Endangerment Finding requires something called a technical support document (TSD) that summarizes all the science research the EPA has done on a subject.

The EPA hadn’t done any on CO₂.

No original research, anyway.

So the EPA did what any college student would do. It copied someone else’s paper.

The 2007 report from the IPCC was available.

In a sentence I love, Drieu Godefridi describes the IPCC as seeing itself as “the all-knowing and all-competent advisor of an internationalist prince.”

It didn’t bother the EPA that the IPCC is a UN political body. Its findings are government opinions, not science.

The science in the Summaries is worked over word-for-word by various diplomats and government officials to make sure it stays on message.

The IPCC, in fact, actually does no science. It surveys and selectively summarizes extant research that supports of its case.

At least the IPCC wasn’t uptight about plagiarism. The U.S. Climate Change Science Program (CCSP) had already copied one of its reports.

The Proposed Endangerment Finding was published in the Federal Register on April 24, 2009.

That was 94 days after Obama was sworn in as President.

So Administrator Jackson made her deadline.

Various versions of Obama’s cap-and-trade bill had been passed by the House of Representatives.

But none could get enough votes to make it through the Senate.

In October 2009, Senators John Kerry and Lindsey Graham threatened to drop The Bomb if some other Senators didn’t switch their votes on the cap-and-trade bill.

The Bomb was EPA regulation of CO₂ under the Clean Air Act.

That was very scary prospect indeed since under the letter of the Clean Air Act, EPA permits would be needed before building almost anything in the U.S.

Kerry and Graham wrote in their New York Times Op-Ed:

If Congress does not pass legislation dealing with climate change, the administration will use the Environmental Protection Agency to impose new regulations.

After the perfunctory public comment period, the Final Endangerment Finding was signed by Ms. Jackson on Dec. 7, 2009.

So it was official. My client was ‘pollutant’. And a ‘danger’.

In November 2009, the leaked Climategate emails finally threw some cold water on the warming panic.

That’s a good place to draw a line under that 2006-2009 history.

I find it helpful to approach science debates as a business reporter.

There was clearly some kind of monopoly that enjoyed dominant market mindshare back then.

The monopolist is a hard thing to put a name on.

Robert Bryce has used the term ‘NGO-corporate-industrial-media-climate’ complex.

Jason S. Johnson, a UVA legal scholar whose work I like, has his own mouthful of a term: ‘Climate Change Science Production and Assessment Complex’.

The Climategate emails provided a peek behind the curtain at how the sausage was being made by the monopoly.

It wasn’t pretty.

The temperature records, for example — Exhibit A against my client — were being systemically ‘adjusted’.

In 2011, economist Richard S.J. Tol — who had been an IPCC lead author — wrote an analysis of the IPCC looking at it as an economist would at any other monopoly.

The IPCC’s sins — the overreach, the haughtiness, the failure to innovate, and the decline in the quality of its product — are “all things that monopolies tend to do, against the public interest,” Tol said.3

As is the fierceness with which the Climate Science Monopoly attacks would-be competition.

Those are otherwise known as ‘skeptics’ and ‘deniers’. It wants to make sure the independents can’t compete.

Lawyers get paid to parse the language of Supreme Court decisions closely.

During the 2006-2009 global warming panic, it may have appeared ‘reasonable’ in Massachusetts v. EPA to ‘anticipate’ ‘greenhouse gases in the atmosphere’ may ‘endanger public health and to endanger public welfare’.

Eighteen years on, that anticipation no longer appears so reasonable.

In fact, it looks like it was dead wrong.

Boston hasn’t sunk into the sea.

The warming has been modest. No tipping points have been tipped.

CO₂’s warming effect — as has been predicted forever — is proving to be self-limiting, the so-called saturation effect. There’s no sign of the dreaded ‘enhanced’ greenhouse effect.

The current forecast for warmer temperatures is probably one we can live with.

Meanwhile, the plants are loving higher CO₂. Recent studies have found ‘global greening’ to be much greater in extent than previously thought. From NASA:

New suspects have been identified in the last 18 years who might be more responsible for The Warming.

One, ironically, is SO₂, an actual pollutant regulated by the 1970 Clean Air Act.

The global cooling effect of sulfate aerosols has been understood since 1815, the ‘Year Without a Summer’.

That year, the sulfates came from an eruption of Mount Tambora, a volcano in present-day Indonesia.

We — and especially China — have been busily reducing how much SO₂ we put in the atmosphere.

A big change came in 2020 when the International Maritime Organization (IMO) put on regulations that drastically limited SO₂ emissions by those big container ships.

And now it’s warmer.

So we were doing a bit of geoengineering all along.

Low clouds and El Niño are also looking much more like bad actors in the recent weather weirdness.

CO₂, might be an innocent bystander.

CO₂ just happened to be in the wrong concentration at the wrong time.

CO₂ wasn’t a ‘pollutant’ in what judges call plain meaning.

“The question,” Alice asked in Wonderland, “is whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

So what exactly was Congress thinking when it wrote the Clean Air Act?

Lawyers get paid to argument over definitions.

I’m kind of lazy. That part of the job I find tedious.

In Hard Times by Charles Dickens, schoolmaster Gradgrind takes Sissy Jupe to task for not knowing the definition of ‘horse’:

Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-four grinders, four eye-teeth, and twelve incisive.

Sissy Jupe knew perfectly well what a horse was. Her father trained them for his circus.

Alice and Sissy got me to thinking.

If you want to teach a child the meaning of the word ‘dog’, you (a) point at a dog and (b) say ‘dog’.

Congress did mention some other — actual — air pollutants in the Clean Air Act.

So maybe I can point at one of them, a real one, and say, “That’s the sort of horse I’m talking about.”

And give an example of sort of research the EPA should have been doing all along.

But which other one?

Miranda has managed to get the window open.

Without my help. I made a point of not watching or saying anything.

I suspected that window had been painted shut decades ago.

So I could have told Ms. Wikipedia she might need a putty knife and a hammer.

But I didn’t say anything.

Anyway, she figured it out.

I’ve read that, where women are concerned, a guy should not be a Mr. Fix-It.

When women vent, for example, guys often make the mistake of thinking women are asking them to solve their problems.

Turns out they just like to vent.

Anyway, we’re venting in the office now. Papers are flying off my desk.

The outside air has put an idea into my brain.

Smog is my ‘dog’.

Or maybe it’s the other way around. My ‘dog’ should be smog.

Here’s downtown Los Angeles in 1958:

Los Angeles recorded its first smog day in the summer of 1903.

The haze was so bad some of the new-fangled light-sensing automatic streetlights downtown turned on in the middle of the day. Some L.A. residents wondered if there had been a solar eclipse.

A surprising number of people pontificate about air pollution without mentioning the weather. It doesn’t seem to exist in rarified atmosphere of environmental law.

Smog days happen in L.A. when there is:

warm to high temperatures

lots of sun

‘stagnant’ air, meaning little or no wind

an inversion layer

L.A. is surrounded by low mountains, so its topography is especially bad. The inversion layer traps the smog in the basin.

The cause of Los Angeles smog was a scientific mystery for a while.

London had its infamous killer smogs.

Those also happened when there was an inversion layer. That happens there when what the British call an ‘anticyclone’ is parked over the Thames.

But the London fogs happened on cold days in winter.

It took no high-tech monitoring devices to see smoke pouring out of chimneys. People were burning lots of coal to stay warm.

There was a bad smog day in L.A. on July 8, 1943, during World War II.

Some speculated that one was a gas attack by the Japanese.

A few smart people were guessing closer.

On Nov. 28, 1944, Gustav Egloff, then president of the American Institute of Chemists, told the Los Angeles Times that he suspected smog came from the improper combustion of gasoline.

Which was a slightly counter-intuitive at the time, because gasoline was rationed during the war. Gasoline consumption by civilians was way down.

But gasoline had also been reformulated by its refiners in a war-time effort to stretch yields. They had added paraffins and olefins, both hydrocarbons.

A Los Angeles County Air Pollution Control District (APCD) was created in June 1947.

The APCD’s smog cops were not popular.

The APCD public relations did its best to give the smog cops some one Adam-12 glamor.

But there was only so much spin you could put on APCD Memo No. 12, “Burning Rubbish -- A Public Enemy”.

The APCD started out by identifying every potential ‘stationary source’ of air pollution in Los Angeles County.

On bad smog days, the APCD would order industrial plants and refineries to shut down.

No source was too small. “Cigarettes Found Contributing to Smog”, the APCD told the Los Angeles Times in October 1956.

Although I don’t think the smog cops went around snuffing out butts.

Backyard incinerators were a big thing in L.A. in those days. The APCD started telling people when they could and couldn’t burn their trash.

People didn’t like that, either.

All those measures helped a little.

But they weren’t the real source of the problem.

And most everybody knew it.

It was those automobiles Los Angelenos loved.

The recipe for Los Angeles smog was finally figured out in 1948 by Arie Jan Haagen-Smit, a Dutch-born flavor chemist then a professor at Cal Tech.

Haagen-Smit worked out that L.A. smog was the product of a multi-stage chemical reaction.

Haagen-Smit definitely qualifies as one of my science heroes.

First off, he was a world expert — probably the world expert — on the smell and taste of pineapples.

For a time, the APCD and the powers-that-be scoffed at Haagen-Smit’s two-stage theory.

So he and one of his students built — using Plexiglas and greenhouse frames — a ‘smog chamber’ in the parking lot of the Air Pollution Control District.

It was a real greenhouse, too. Spinach and some other plants were good smog detectors. Those grew, or tried to grow, in the smog chamber.

In 1956, S. Smith Griswold, head of the APCD, came up with a publicity stunt in which he spent two hours in the smog chamber with the gas cranked up high, well above what it was on bad smog day in L.A.:

Griswold, who had been a football player in college, came down with bronchitis.

He also said the smog made him ‘high’. And not in the good way.

Here’s Haagen-Smit’s recipe for L.A. smog. Don’t try this one at home:

Nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) in the tailpipe exhaust absorbs UV from sunlight and splits into nitric oxide (NO) and a free oxygen atom (O).

The free oxygen atom (O) combines with atmospheric oxygen (O₂) to form ozone (O₃).

Ozone is itself an irritant, but some of it also feeds back to react with plain old nitric oxide (NO), also in the tailpipe exhaust, to generate some additional nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) along with oxygen (O₂).

Unburned hydrocarbons in the tailpipe exhaust react with hydroxyl (OH) radicals to create peroxyacyl nitrates (PANs).

The peroxyacyl nitrates are the eye irritants in smog. They also give it that dirty light tan-gray color.

In over-simplified science, VOCs — volatile organic compounds — get demonized as ‘smog precursors’.

Strictly speaking, a volatile organic compound is one with a boiling point over 50°C., meaning it will evaporate into the air at room temperature.

So perfume is a VOC. The bulk of VOCs in ambient air actually come from plants.

Careful writers talk about ‘reactive hydrocarbons’ (HC) rather than VOCs.

China, which knows a thing or two about air pollution first-hand, restricts its definition to compounds that “originate from automobiles, industrial production and civilian use, burning of all types of fuels, storage and transportation of oils, fitment finish, coating for furniture and machines, cooking oil fumes…”, etc.

From 1948 to 1958, the APCD ran an industrial-scale research lab trying to figure out to deal with L.A. smog.

It finally did the right thing and hired Haagen-Smit as a consultant.

The APCD science lab soon knew everything there was to know about L.A. smog.

It studied wind patterns, traffic flow, geographical contours, photochemistry, the inversion-layer, the works.

My favorite APCD research project is the Navy blimps.

It rented those to sample the upper reaches of the airshed.

When people saw the blimps emerge from the smog, they reported them as UFOs.

Griswold invited the public to send in ideas for how to deal with L.A.’s smog.

The APCD’s Inventor’s File got thick in a hurry. “Everybody,” the L.A. Times wrote, “has a smog remedy.”

Some inventors thought big. They suggested putting giant fans on the mountains to blow the smog away.

A ‘smog sewer’ was an idea that got some traction. The L.A. Times wrote about it in 1954: “Vast Air Sanitation System Proposed As Smog Solution.”

The smog sewer would have carried the smog off somewhere else.

Where that ‘somewhere else’ would be was a little hazy.

In one design, giant vertical plastic pipes would have allowed the smog to be pumped up and over the inversion layer.

By 1957, the APCD had grown tired of studying ideas submitted by nut jobs.

It knew the hard nut it had to crack was automobile exhaust.

“Until a cure is found for the auto exhaust,” Griswold wrote in an Op-Ed that year, “we can look for little reduction in smog.”

There were ideas in the Inventor’s File for that, too.

One was a sort of afterburner for cars, a ‘blowby device’ that would further burn unburned hydrocarbons.

Also buried in the APCD slush pile was a letter from an engineering firm claiming it could end smog within three years with a muffler-like invention.

The catalytic converter was invented in France way back in 1898.

During World War I, Eugene Houdry, a French chemical engineer who knew a lot about catalysts, tried to come up with a better aviation gasoline for those Spad biplanes.

Houdry also had a passion for fast cars. After the Great War, Houdry starting using catalytic metals to refine high-performance gasolines.

Early internal combustion engines would ‘knock’. Knock happens when a small amount of residual gasoline vapor ignites during the exhaust stroke of the piston.

After World War I, the search was on for something — anything — that would inhibit knock.

One answer was staring people in the face: a blend of gasoline with 20% or 30% ethyl alcohol.

In the U.S. of 1921, politics got in the way of that one.

It was Prohibition. No U.S. corporation in its right mind would to invest in a factory to make alcohol in industrial quantities.

Some politician channeling Carrie Nation (she died in 1911) might show up with a hatchet and shut the place down.

Also, moonshine wasn’t really patentable, which the corporations would have liked. Any idiot could make it. Many did.

Tetraethyl lead was an anti-knock agent.

It took a few years to figure out how to make it cheap.

The first ‘Ethyl’ gasoline was sold to the public on February 1, 1923 in Dayton, Ohio. The price for premium was 25¢ a gallon. Regular was 21¢.

Gasoline came in colors back then. The pumps had clear glass windows. Ethyl was red.

The lead in the tetraethyl lead showed up in the exhaust fumes.

Lead poisoning among miners and metal workers was well-known to the Greeks and the Romans.

In the opinion of Vitruvius, engineer of one of Rome’s aqueducts, “Water is much more wholesome from earthenware pipes than from lead pipes, for it seems to be made injurious by lead…”

One of the co-inventors of tetraethyl lead — those being Thomas Midgley, Jr. and Charles F. Kettering of Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company, DELCO — developed a minor case of lead poisoning during the research. Midgley had to take a month off to recuperate in February 2023.

The U.S. Surgeon General was concerned enough about lead in automobile exhaust to ask the Bureau of Mines in Pittsburgh to run animal tests in the fall of 1923.

The Bureau concluded that the danger to the public of breathing lead in from automobile exhaust was probably negligible.

Opinions will vary on that. It’s highly complicated.

Lead is taken up by plants from the soil and ingested by humans in food. Dark chocolate is especially notorious.

Most ingested lead gets excreted out the human tailpipe.

What you need to look for is a buildup, if any, of the ‘body burden’ of lead. Then you need to relate that, if you can, to the familiar neurological symptoms.

But many people have high body burdens of lead yet show no symptoms.

And it’s an an entirely different situation for children, whose brains are developing.

Anyway, there was incentive even in the 1920s and 1930s to get the lead out.

In the late 1930s, Houdry found he could refine a high-octane gas without tetraethyl lead using one of his catalytic process.

Houdry’s “Nu-Blue Sunoco” formulation went on the market in 1937. I assume its color was blue.

High-octane aviation gas was a critical U.S. advantage during World War II. It significantly increased the combat performance of allied fighter aircraft. By 1942, fourteen of Houdry’s fixed-bed catalytic units were producing high-octane for the U.S. Army Air Corps.

So using catalysts on gasoline was a known technology.

In 1951, Popular Mechanics had a short mention of a ‘catalytic exhaust muffler’ being used on warehouse fork lifts. It removed the carbon monoxide that would otherwise poison indoor workers.

After smog became a public issue, Houdry got interested and designed a better catalytic convertor for passenger cars. He started a company called Oxy-Catalyst.

There have been numerous improvements over the years, but basically a modern three-stage catalytic converter deals with what comes out of your car’s tailpipe as follows:

Both of the nitrogen oxides (NO₂, NO) are reduced to ordinary nitrogen (N) and oxygen: NOx→Nx+Ox

Carbon monoxide (CO) is oxidized into (harmless!) CO₂: CO+O₂→CO₂

The unburned hydrocarbons are oxidized into carbon dioxide and water: CxH₄x+2xO2→xCO₂+2xH₂O

In June 1966, California Governor Edmund G. (Pat) Brown signed a law requiring ‘anti-smog devices’ — basically catalytic mufflers, although there were several others — be installed on used cars when they changed ownership.

The problem was that ‘catalytic mufflers’ were an aftermarket item that had to be bolted onto a car by a mechanic at a place like Midas.

It would make much more sense for catalytic converters to come as standard equipment on new cars and get installed on the assembly line.

The (then) Big Four U.S. automakers — Ford, GM, Chrysler and American Motors — promised they were looking into that.

But they were basically just dragging their feet.

In 1967, the legislature and new Governor Ronald Reagan created a state-wide California Air Resources Board. It made Arie Haagen-Smit chairman.

A long, drawn-out battle took place between the State of California and the automakers.

Robert F. Kennedy — RFK Jr.’s father, one of California’s two Senators until his assassination in June 1968 — came up with a novel political strategy for the state to use.

Kennedy advised otherwise liberal California to ally itself with the Jim Crow South and start taking about “state’s rights”.

Although in the South that’s pronounced ‘rats’. As in, “I got my rats!”

California would go its own way.

In early 1970, the California Air Resources Board lost patience with the Detroit automakers.

It put in place regulations that required catalytic converters on all new vehicles sold in the state.

The automakers could see the writing on the wall.

They turned to the Federal government for help.

They wanted the Feds to step in and pre-empt those crazy state governments before they set 50 different standards.

The automakers got something they could live with, the Clean Air Act of 1970.

Fast forward: cars today with internal combustion engines emit 1% of the bad stuff they did in the 1960s.

Smog, my ‘dog’, was an actual air pollutant that required some real science to figure out.

1970

I close the book I was reading about the history of smog.4

My eyes hurt. Maybe it’s something in the air.

Smog is definitely irritating.

I once played in a water polo match in downtown Los Angeles on a bad smog day.

It was in the old outdoor pool originally built for the 1932 Olympics.

It’s still around. I see where they’re giving it a make-over and planning to use it for the diving competition in 2028.

You could see the crud in the air.

In the excitement of the game, you didn’t notice it.

Afterward, you felt like some Torquemada had put an iron strap around your chest and ratcheted it tight.

It was hard on the horses, too, after they got out of the pool.

You can’t mention water polo without getting in that old joke.

Fortunately, the effect didn’t last. The saving grace of being young and stupid is most likely you’re fit.

In my smog reading, I saw lots of footnotes to articles about the health effects of ozone.

I start wondering: Am I going to die?

I mean sooner.

Like, I grew up in L.A., dude, breathing that stuff.

The EPA’s page about the health effects of ozone says: “The predominant physiological effect of short-term ozone exposure is being unable to inhale to total lung capacity.”

That was definitely me.

Other symptoms the EPA lists are:

Cough

Throat irritation

Pain, burning, or discomfort in the chest when taking a deep breath

Chest tightness, wheezing, or shortness of breath

And the effect is usually transitory.

The EPA’s national standard for ozone has been all over the place since 1970.

The one constant is that it gets set by politics.

The 1970 Clean Air Act required the EPA to set a safety threshold, a National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS), for photochemical oxidants.

‘Photochemical oxidants’ are not quite the same thing as ozone (O₃).

But O₃ is easier to measure, so it took over as the standard bearer for smog.

Ozone concentrations are very much weather- and topology- related.

So a national standard was always a somewhat dubious proposition.

Other U.S. cities have smog.

Denver, Phoenix and Houston come to mind.

But lots of cities don’t.

And Los Angeles tops the charts. It’s a total outlier.

Making those other cities take the same expensive regulatory measures as Los Angeles didn’t seem exactly fair.

In 1971, the EPA Administrator at the time, William Ruckelshaus, picked a national ozone standard out of the air: 0.06 parts per million (ppm).

That number was an eye-opener. L.A.’s standard at the time was 0.10 ppm.

The natural background level for ozone is somewhere between 0.02 ppm and 0.06 ppm.

But Ruckelshaus was a consummate political animal. He’d learned from one of the best, Richard Nixon.

Ruckelshaus knew the Congress of 1971 was pro-public transit and anti-automobile.

So it would be delighted to have ozone pollution as an excuse to pass laws that did things like limit vehicle miles travelled (VMT).

With a stroke of Ruckelshaus’s pen, all sorts of cities now occupied ‘non-attainment zones’.

The EPA science behind the 0.06 ppm number was pretty hokey.

A pattern the EPA will repeat.

But the Administrator needed a number.

Three studies about health effects of ozone were considered.

They were all pretty questionable.

And even then their findings were pretty much ignored.

A handful of people started complaining about eye irritation at ozone levels above 0.10 ppm. Which, to repeat, was L.A.’s standard.

A single study of 137 severe asthmatics concluded they did not have more frequent attacks at ozone levels below 0.13 ppm.

They maybe started to show effects above 0.25 ppm.

Another study, one I could have related to, asked high school athletes to talk about their performances after track meets. They didn’t complain when ozone levels were below 0.16 ppm.

In the wisdom of the Congress of 1970, cost and technical feasibility were not to be considered in setting national air quality standards.

Nor was the size of the population ‘at risk’.

Or that nature of that population. It might be only children, or the elderly, or only those with a preexisting condition, such as asthma.

Of the general population, those with asthma who might benefit slightly from a lower ozone standard were estimated to be 0.25%.

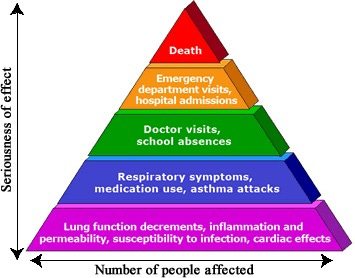

Health risks slide down a scale of severity: mortality, increased hospital admissions, bronchitis, respiratory symptoms, lost work days, finally down to what the EPA calls minor restricted activity days (MRADs).

The EPA publishes a helpful pyramid to visualize this:

My attention, naturally, is drawn to the top of the pyramid.

After that water polo game, I probably said something like “That was killing me.”

Now I want to know if that’s literally true.

In 2013, a writer I really like, Steve Milloy, did a DIY science project of the sort of which I fully approve.

Milloy made a Freedom of Information Act request to the Veterans Administration West Los Angeles Medical Center, asking for the day-by-day tally of emergency room admissions for asthma for the period between January 1, 2009, through December 31, 2011. There were 726.

Milloy then got the ambient ozone measurements for the area from CARB. Those are easy to get.

He put the two together in a spreadsheet and found zero correlation. High ozone was not related to emergency room admissions for asthma, at least not at that VA.

Studies that find ‘no correlation’ don’t get much attention.

Although they should.

The media is not very interested in headlines that say “Nothing to see here.”

So Milloy published his study on his own website, JunkScience.com. Highly recommended.

‘Junk science’ may sound a bit harsh.

So ‘advocacy science’, if you want to be polite.

As CO₂’s lawyer, I’ve come to know junk science when I see it.

Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart in 1964 famously said he knew pornography when it saw it.

Supreme Court justices back in the 1960s had all the luck. They got to watch soft-core all day for those free speech cases.

A sufficiently shady lawyer has no problem recognizing junk science.

Its style is that of legal argument.

When an honest scientist comes up with a hypothesis, a necessary if unpleasant part of the job is to start thinking up experiments and observations that might falsify the hypothesis.

You have to be willing to slay your darling, no matter how much you love it.

Advocacy science is like courtroom argument. You never admit you might be wrong.

James Lovelock deplored this as far back as 1979.

Lovelock was the inventor of the electron capture detector, which found chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in the stratospheric ozone layer.

So he was a hero of ecological science.

But Lovelock hated the style of argument used by another paragon of environmental movement, Rachael Caron:

When Rachel Carson made us aware of the dangers arising from the mass application of toxic chemicals, she presented her arguments in the manner of an advocate, not a scientist. In other words, she selected the evidence to prove her case. … Since then a great deal of scientific argument and evidence concerning the environment is presented as if in a courtroom or at a public enquiry.

Which, Lovelock predicted, was going to be very bad for science.

One strategy to win a courtroom argument is to pile on evidence.

Tons of it, even if it’s weak. Item after item.

But in the theory of science, a single well-designed experiment or test is enough to falsify a hypothesis, no matter what everybody else is saying about it.

Those who argue from ‘consensus’ or the ‘consilience of evidence’ are often covering for the fact that their pet hypothesis is not, in fact, falsifiable.

It’s an article of their faith.

So don’t you dare entertain the suggestion it could be false.

They’ll call you names. ‘Denier’ rhymes with ‘blasphemer’.

In the years after Lovelock’s comment, the IPCC proved the reductio ad absurdum of mistaking legal argument for science. Its mission has always been to build the case against humans, not understand climate.

A few keywords that should trigger an advocacy science antenna are: ‘assessment’, ‘meta analysis’, and ‘re-analysis’.

Assessments start out resembling compilations.

Now, compilations can be a useful thing to have someone make for you.

But in a ‘assessment’ you need to worry about what studies an opinionated assessor left out of the compilation. You’re not seeing those. The IPCC assessments have that problem big time.

A ‘meta analysis’ looks at a number of studies and tries draws a single conclusion.

Sometimes a ‘meta analysis’ is done by someone who wants make a point and appear superior in knowledge — ‘meta’ — to those other researchers, who did the dog work.

When the EPA does a ‘meta analysis’ it uses a very peculiar set of voting rules for epidemiological studies.

A single study is enough to convict, even if all the other studies are inconclusive.

Likewise, an acquittal requires all studies be unanimous.

Which is something you almost never see coming out of the academic world. The rules force the EPA to err — very badly sometimes — on the side of extreme caution.

The EPA is so afraid of making a finding that is a false negative it will indulge many that are false positives.

‘Re-analysis’ is spreadsheet science.

Someone else has done the hard work of designing a study and collecting data, often for some other purpose entirely.

The spreadsheet scientist comes along, grabs the data, and looks for ways to re-slice and re-dice it to make some new point they want to make.

In the worst case, this is called ‘p-hacking’, where the strategy is try-this-and-try-that until some statistically significant (p < .05) relationship falls out of the data.

‘Statistical significance’ sounds good, but it’s not all it’s cracked up to be. If you try enough times, statistical significance emerges from random data.

But I’ve gotten distracted by math.

I still need to figure out if I’m going to die.

An L.A. Times headline from 2006 is not reassuring: “Study Doubles Estimate of Smog Deaths”.

I read the story.

It’s worst than I thought.

Not only am I going to die, I won’t even be able to pass my genes on to my progeny.

“The data indicated that for every 14 parts per billion increase in ozone, we had an approximate drop of 3 million sperm per millimeter,” said the lead author of a related study.

Apparently that only happens on smoggy summer days. I’ll keep that in mind.

I look at “Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Mortality,” a 2009 study by Dr. Michael Jerrett (of UCLA) et. al. published in the New England Journal of Medicine.5

The American Cancer Society’s Cancer Prevention Study II started in 1982 and followed 1.2 million Americans for 24 years. It was designed to study the effects of lifestyle, smoking, and so on.

During that time, 491,188 people enrolled in the study died. An official cause of death was available for 99.3% of those.

Dr. Jerrett’s idea, not unlike Steve Milloy’s, was to get data on daily maximum ozone concentrations for the addresses of the study subjects and — controlling for all the zillion other factors that might affect their mortality — try to come up with an unexplained residual, which might be the contribution of ozone to mortality.

I wouldn’t call Dr. Jerrett’s study junk science. But it doesn’t convince me to worry, either.

Air pollution control boards put up monitoring stations where they think their might be air quality problems, such as near freeways or at the port.

They don’t have the money to do random samples of air quality on every leafy suburban cul-de-sac.

The ‘ecological fallacy’ comes from attributing the average traits of a population to all segments of that population.

It’s like saying I don’t need to know how you voted, because I know the numbers on how the people in your precinct voted.

It’s a very big if to assume you can determine the quality of air someone is breathing from their home zip code.

First off, obviously, over the years of the study, some people will have moved.

Second, people spend a lot of time — maybe 70% — at work, or getting to and from it.

Third, they spend a lot of time indoors. Especially the elderly, who are most likely to have health problems.

Indoor air quality has long been an EPA blind spot. Most of the allergens and irritants known to aggravate asthma, for example, originate inside the home.

Fourth, boundaries for census tracks and zip codes can aggregate very different neighborhoods.

In Los Angeles, for example, zip code 90049 includes the ultra-wealthy neighborhoods of Brentwood, Mandeville Canyon, Westwood, and Bel Air, and also much less wealthy neighborhoods such as South Valley and Mid-City.

That zip code’s median income in 2017 ranged from about $208,000 in Bel Air, which is 80% white, to $44,000 in Mid-City, which is about 10% white.

One 2002 national study similar to Dr. Jerrett’s used data from precisely 3 monitors for the entire Southern California region.

So there some big questions about Dr. Jerrett’s input variable, ozone exposure.

I’ll just mention that ‘cause of death’, especially for the elderly, is also a bit problematic.

‘Old age’ is not a cause of death.

So the elderly get written up as dying from something. Heart failure or pneumonia, often. The latter is notoriously known as the “old man’s friend.”

The usual output of environmental epidemiological studies is a metric called relative risk (RR). You get by dividing the risk of death in one group by that of another group.

An RR of 1.0 means the outcomes of both groups is the same, so whatever distinguishes them is probably unimportant.

An RR can be less than 1.0, meaning one group, usually the smaller, is heather than the other.

People living in (a) California (b) Los Angeles Country, and ( c ) the South Coast Air Basin all have an RR around 0.88 compared to the rest of the U.S.

That’s presumably because they have higher incomes, better health care, better diets, less smoking, and so on.

Those things like higher income are the ‘confounding factors’.

Dr. Jerrett, after trying to control for, in his words, a “total of 20 variables with 44 terms” for individual characteristics that “might confound or modify the association between air pollution and death,” came up with some RR numbers for exposure to ozone in ambient (outdoor) air.

A 0.01 ppm increase in exposure to ozone, he calculated, elevated the relative risk of death from the following causes as follows:

cardiopulmonary causes (relative risk, 1.014; 95% CI, 1.007 to 1.022),

cardiovascular causes (relative risk, 1.011; 95% CI, 1.003 to 1.023),

ischemic heart disease (relative risk, 1.015; 95% CI, 1.003 to 1.026), and

respiratory causes (relative risk, 1.029; 95% CI, 1.010 to 1.048).

An RR of 1.03 is not nothing. But it’s not very big, either. And definitely small enough to be an artifact of the study design.

I make a sticky note for my heirs and put it in the folder with my will: if I succumb to ischemic heart disease, don’t bother to sue the Air Pollution Control Board.

The Federal Judicial Center Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence says an RR should be over 2.0 to merit attention. Otherwise, a judge will tell a lawyer: fuhgeddaboudit.

The RR of death from all causes for current smokers is 2.80 for men and 2.76 for women.

Speaking of cancer, ozone in ground-level air may even have a protective effect. We know ozone in the stratosphere does.

Ground-level ozone may block UV, and thus reduce skin cancer.

There was some Strangeloveian findings in the 1950s that tried to get Los Angelenos to look on the bright side of their smog.

If there had been an atomic attack on a smoggy day, fewer of them would have gotten fried.

I’m still a little worried.

I look to see how L.A. was doing during the years of my misspent youth.

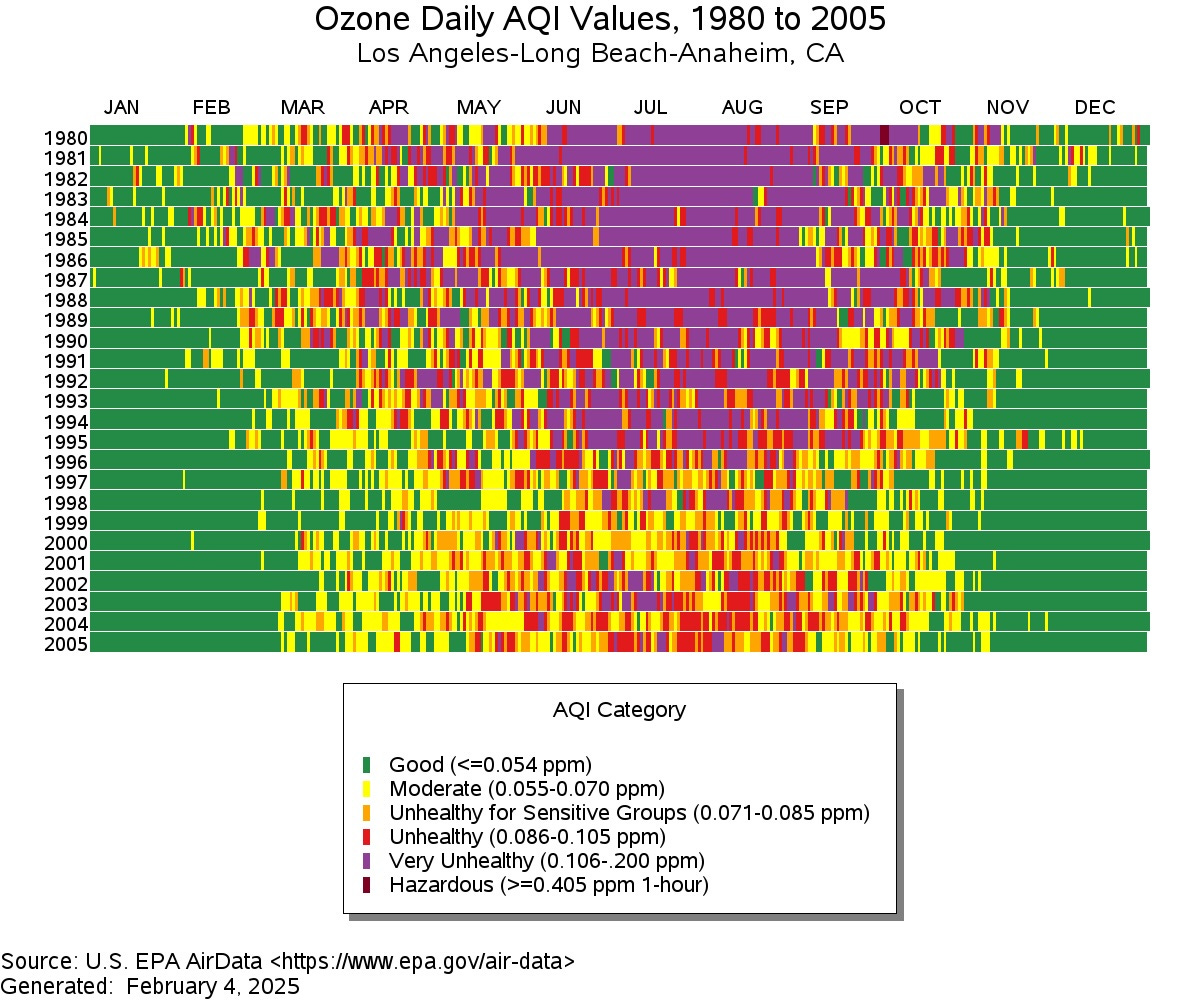

At least it was getting better. You can see the summer ozone season shrinking:

Actually, Los Angeles was doing pretty well before there even was an EPA. The agency’s birthday is December 2, 1970.

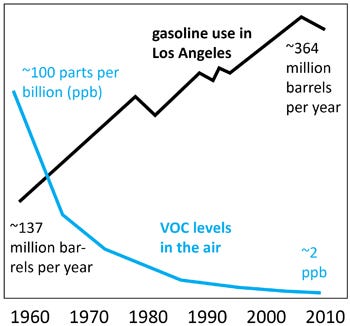

Look at the blue line’s decline in VOCs between 1960 and 1970:

VOCs have come down 98% since 1960, despite L.A. having a 37% increase in population in that time. And those people using three times as much gasoline.

I guess commutes have gotten longer. Or slower.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that Los Angeles, with its relatively affluent and well-educated population, should have had some success dealing with smog on its own in the 1950s and 1960s.

One idea in the APCD’s slush pile of smog inventions, for example, was submitted by Rockwell International, which presumably came up with it when it wasn’t doing aerospace work for NASA.

The ‘Kuznets Curve’ relates affluence to desire to improve the environment:

When a country is just starting up the ladder of economic development, it will accept environmental damage. The U.S. in the 1800s certainly did.

After a country becomes more affluent, it feels it can ‘afford’ to start taking care of the environment. That’s pretty clearly going on in China right now.

After World War II, the newly affluent U.S. middle class moved to the suburbs so they could have good schools and lawns to mow.

In L.A., they discovered they couldn’t let their kids play outside on smog days.

So they took action on their own, no waiting for the federal government.

But maybe L.A. is just weird. A lot of people think that.

I decide to look at a different city.

Before there was smog, ‘air pollution’ was synonymous with coal smoke.

The first complaint about coal smoke was made by Queen Eleanor of England in 1257.

First complaint to get written down by a scribe, that is.

I’m sure some Neanderthal complained about the cave being too smoky immediately after the discovery of fire.

In the U.S., coal surpassed wood as an energy source in 1885.

Coal smoke became a problem in industrial cities such as Pittsburgh.

The first city ordinances restricting smoke go back to Civil War days.

But smoke abatement became a hot topic among civic betterment groups during the Progressive era.

Coal smoke was unaesthetic and unpleasant.

But people back then had mixed feelings about it.

They were a little proud of it: the smoke was a sign their city had industry and jobs.

It also didn’t strike terror into people as a health risk back then.

Coal smoke was thought to have antiseptic properties. Inhaling it was prescribed for sufferers of tuberculosis.

Variations on that folk-medicinal notion have been around for a long time.

During London’s Great Plague of 1665, people kept the coal fires roaring to burn up ‘noxious particles’ in the air. They believed those were responsible for the Plague.

The civic betterment groups made only minor progress against coal smoke until natural gas came around in the 1930s.

Natural gas sold itself to consumers as cleaner and more convenient for home heating and cooking. People without servants could wear white clothes again.

It’s hard to find charts for air quality that go back before 1970, the birth year of the EPA. It keeps most of the data.

I finally found a chart that uses some of the old measures for soot in the air.

TSP or ‘total suspended particles’ was measured — reasonably accurately — by passing air though a filter, which could be weighed before and after.

For a quick-and-dirty result, the color of the previously white filter could be matched against standard gray squares on a printed card. There are almost two centuries of data collected using the so-called ‘British Smoke’ method.

I have to mention the ‘dustfall’ method, just because it was a high point of low-tech air quality monitoring.

An open bucket was left out — for example on a factory floor — and the soot weighed or measured at the end of the day.

Here’s TSP and dustfall for Pittsburgh going back to 1910:

You can see a steady decline long before the EPA. And maybe even see the natural gas drop in the 1930s.

In an unguarded moment, Douglas Costle, administrator of the EPA under Jimmy Carter, said that in the 1960s the states did more to cut sulfur dioxide (SO₂) and particulate pollution than the EPA did in the 1970s.

Maybe I’m a cynic.

But if you look at charts for air quality dating from 1970, when that Clean Air Act passed, it looks like the EPA could have done a victory lap around 1992. The actual air pollutants were all heading down.

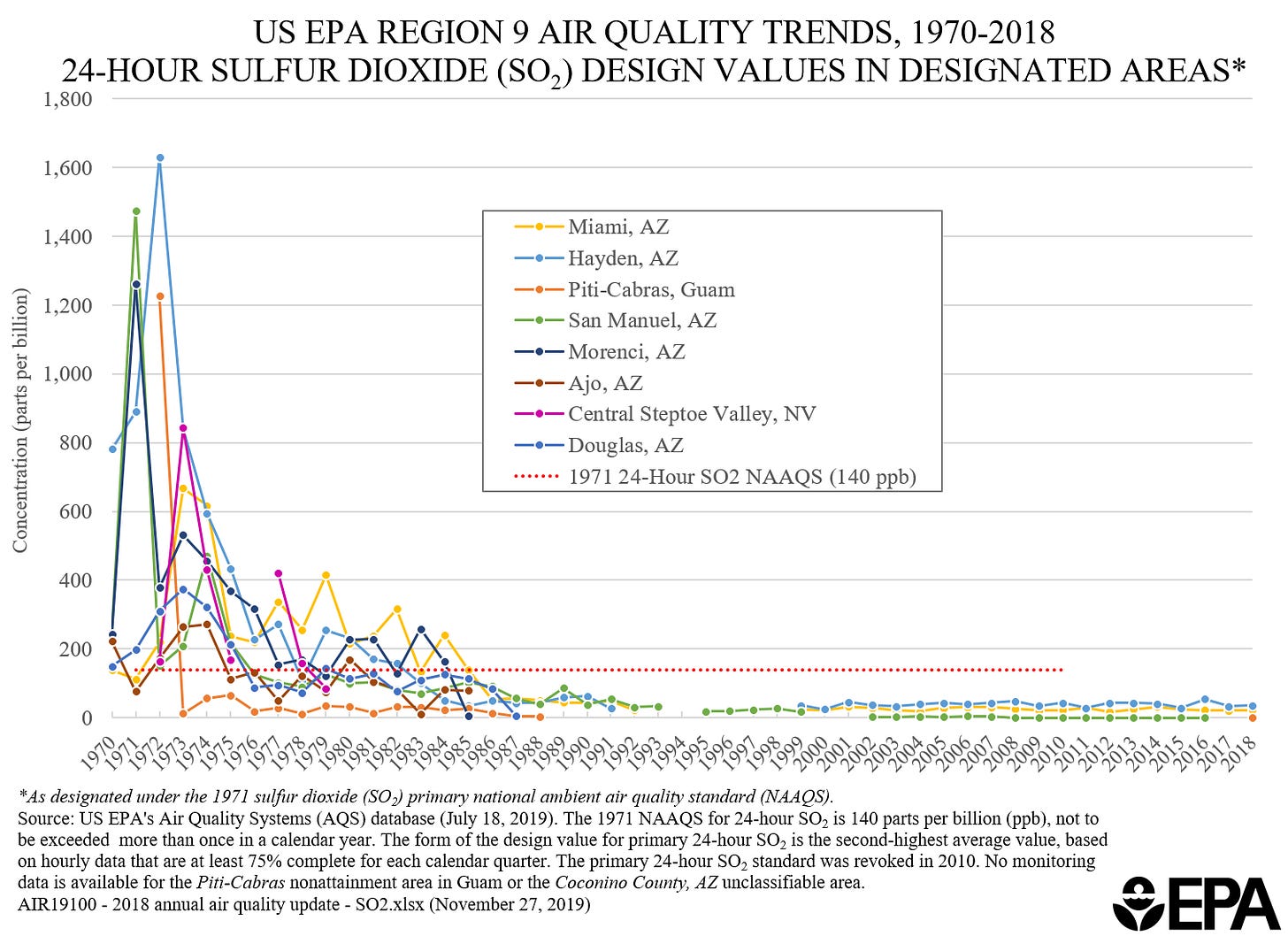

The last domino to fall was sulfur dioxide, SO₂.

That’s because during the energy crisis of the 1970s, coal was going to guarantee U.S. energy independence.

For a time, Jimmy Carter, Congress, and the anti-nuclear environmental groups were all-in on coal for generating electricity. Its use increased.

The coal push suffered from some pork-barrel politics that made SO₂ emissions worse than they needed to be, and more expensive to deal with.

Senators from states around Appalachian couldn’t resist writing in privileges for that region’s high-sulfur coal over the low-sulfur stuff found in Wyoming.

The EPA required nearly every coal-burning power plant in the country install expensive scrubbers.

Those took the SO₂ out to be sure, but also conveniently guaranteed they would be able to burn Appalachian coal.

It took George H.W. Bush’s 1990 SO₂ emissions trading scheme to put sense into the regulations and get SO₂ emissions heading down.

Here’s SO₂ in the air. The locations in Arizona are, probably not coincidentally, near the Navajo Four Corners coal-burning power plant:

Like I said, Mission Accomplished.

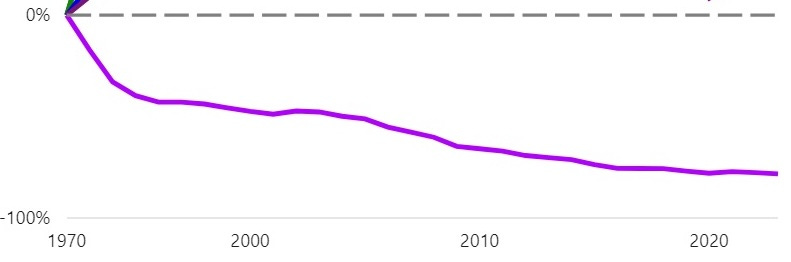

The EPA itself puts out one final chart of interest to me.

The purple line, the EPA says, is an ‘aggregate’ measure of the six criteria air pollutants, meaning those have a NAAQS national standard.6

It’s the shape of the EPA’s line that interests me:

As that purple line approaches the asymptote, additional regulations had diminishing returns.

Less bang for the buck. It costs more and more to get rid of less and less.

That was the motivation behind Ronald Reagan’s 1981 executive order requiring new regulation be subjected to cost-benefit analysis.

The question the EPA could never bring itself to answer was: “How clean is clean enough?”

In fact, the EPA refused to ask the question.

So instead of declaring Mission Accomplished on classic air pollution, the EPA did just the opposite. It doubled down.

As a first strategy, you can continue to try to regulate something into the ground.

Somewhat literally. Below natural background level.

You can justify that if you believe in the linear no threshold (LNT) theory.

That holds there’s is no level that’s safe enough.

So if money is no object, you can try to get rid of it.

Such a quixotic quest usually proves to be absurdly expensive.

Although they are an endless source of pork for those doing the mitigating, as in the EPA SuperFund clean-ups.

As an alternative strategy, you can find some new air pollutants to worry about.

The EPA discovered PM2.5 in the 1990s.

Large particles in the air, such as those from dust and smoke, you can see.

The lungs of air-breathers evolved to deal with dust after they emerged from the swamp 420 million years ago.

They developed those little cilia.

And they learned how to cough and spit.

Politely, of course.

PM2.5 happens because perfectly clean air is not found in nature.

Real-world ambient air contains tens of thousands of suspended particles of different sizes.

Improved optical sensors in the 1990s made it possible to count not only the number of suspended particles in a cubic meter of air — the old ‘total suspended particles’ metric — but also break them down by size.

The EPA was like a kid with a new toy.

The old TSP metric got replaced with two new ones: PM10 for larger diameter particles and PM2.5 for those less than 2.5 µm.

That’s 2.5 millionths of a meter.

It’s hard to comprehend how small that is.

A human hair has an average diameter of 70 µm. So 28 times smaller than that.

A particle with diameter 2.5 µm will happily pass through a high-quality N-95 mask of the sort you may have worn in Covid days.

It’s small enough to be carried deep into your the lungs when you inhale.

It’s also small enough to exit your lungs when you to exhale.

Here’s some abbreviated math on PM2.5:

The amount of air inhaled by an adult breathing at rest ~ 10,000 liters/day = 10 m³/day ~ 292 M m³ over 80 years.

At one EPA National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) for PM2.5, 15 µg/m³, an adult will inhale 4.38 grams, or 0.88 teaspoon, of PM 2.5 over those 80 years.

Which that adult just might also have exhaled.

We need to ask if it accumulates. Recall the business about lead’s ‘body burden’.

In autopsies, mineral particulate matter in human lungs is around 0.1 gram. So not much there.

The notion that environmental protection makes progress is an odd one.

Technology does advance. We can now detect minute levels of all sorts of things.

Just because we can now detect them, however, doesn’t mean we need to rush off and protect ourselves from them.

Justifying that requires embracing a highly pernicious doctrine, the ‘precautionary principle’.

The precautionary principle says no science required. Regulate it anyway.

We’re clueless, but we should put a stop to the thing because it sounds bad.

The EPA really wanted to regulate PM2.5. It just couldn’t figure out why.

PM2.5 has been studied for decades now.

There’s still no convincing etiological (medical) theory of how those fine particles travel from your lungs and affect your heart or whatever they are supposed to be doing.

So the evidence that links PM2.5 to things like higher risk of cardiovascular disease comes from those statistical studies.

The ones that have the zillion confounding factors.

Note that ‘higher’ is one of those legal argument words lawyers love. No one can deny that 0.00001 is higher than 0.00000.

But don’t take my word on this. The EPA knows it has a problem using statistical studies.

In 1996, Dr. George T. Wolff, chair of the EPA’s Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee (CASAC), wrote that those studies leave:

...many unanswered questions and uncertainties regarding the issue of causality. The concerns include: exposure misclassification, measurement error, the influence of confounders, the shape of the dose-response function, the use of a national PM2.5/PM10 ratio to estimate local PM2.5 concentrations, the fraction of the daily mortality that is advanced by a few days because of pollution, the lack of an understanding of toxicological mechanisms, and the existence of possible alternative explanations.

That uncertainty hasn’t stopped the EPA.

PM2.5 was drafted to be a soldier in the EPA’s war on coal, after large particles and SO₂ came reasonably under control.

I’m not against medical research, or well-designed epidemiological studies.

Who knows? Someday it may be perfectly obvious that Alzheimer’s is caused by something we’ve not yet thought of.

I’m against the rush to judgement.

A statistical study should be a first pass.

It can suggest things that should be looked at in more detail. It can also save effort by ruling things out.

The next step, however — which can take time and be expensive — is to design new studies that can actually get to the causal question.

Such as, outfit some people with personal air monitors and track their health for 15 years. Or use tracer particles to see if they really end up in the heart.

But the something-or-other Complex is an awesome sight when it swings into full production. Study after study gets done replicating findings.

Without attempting to get to the built-in assumptions of the original ones.

The production rate of the Complex is behind media clichés about ‘growing evidence’.

The media doesn’t care if the ‘growing evidence’ is any good.

On the flip side, regulating things that don’t actually need regulation can be very expensive.

Which brings us back to the case of my client, CO₂.

Let’s assume Administrator Zeldin finds for CO₂ and says the 2009 Endangerment Finding no longer applied.

What would a post-CO₂ or post-GHG EPA look like?

I make a list of the EPA’s current regulations aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

One linguistic thing is glaringly obvious. The word ‘emissions’ has become synonymous with CO₂ emissions. We’re going to start asking: “Emissions of what?”

A post-CO₂ EPA is not really going to be about the EPA.

The ‘other’ agency involved is the Department of Energy, the DOE.

As the NRC was the ‘Just Say No’ agency for nuclear power, the EPA has been the Just Say No agency for fossil-fuel power.

The EPA’s power plant rule of April 25, 2025 requires existing coal-fired power plants and large new gas-fired power plants to achieve 90% reductions in GHG emissions by 2032.

Getting rid of that would be a big win for them.

An existential one, in fact, since it gave them a ‘choice’ between using carbon-capture technology that doesn’t exist, or shutting down.

By the way, the EPA first came to believe it had the magical power of ‘technology forcing’ back in 1970 with catalytic converters.

But catalytic converters back then were a working, existing technology that only needed a little shove to be manufactured cheap.

A more interesting question is whether coal might follow CO₂ into rehab.

In a February 11 2025, interview Energy Secretary Chris Wright told Bloomberg “America’s War on Coal Ends Now.”

In an ‘all of the above’ energy strategy, coal has some attractions. As opposed to natural gas, the fuel can be inventoried on site.

Short-term, Wright will try to keep existing coal plants from being shut down.

Coal plants didn’t have a chance of staying open if they had to capture CO₂.

Coal is complex mineral, and there are several types.

Whether coal can be burnt cleanly and economically with respect to all the stuff in it is a technology question somebody — not the EPA — should give honest research.

The scrubbers that remove SO₂ from coal smoke, by the way, also capture most of the mercury and other elements in coal people panic about.

Vehicle mileage standards are another big thing that might go away. That might well affect you personally.

The so-called CAFE standards — corporate average fuel economy — date back to the oil crisis of the 1970s.

Back then, everyone was worried about the U.S. running out of oil. And it needed to be energy independent.

Things have changed. The U.S. now produces more crude oil than any country.

More than any country ever, according to the EIA on March 11, 2024.

The U.S. also apparently has plenty of oil and gas in the ground.

The best thing for it to do with that bounty or blessing would be a good question for Congress to take up. It might not be the worse idea to put some of the proceeds in a sovereign wealth fund, as Norway did decades ago.

In Blob-like fashion, the EPA took over mileage standards from the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA), which originally had charge of them.

If we don’t really have to use less oil, it’s only that (harmless) bit of CO₂ that comes out of your catalytic converter that’s the legal justification for the EPA to be concerned with the mileage of internal combustion vehicles.

The moving of the goalposts on gas mileage in recent years has been the EPA’s way of making industrial policy. It’s a not-so-subtle way of telling you to go out buy an EV.

After, of course, it told the automakers they had to make them. Which, from the losses we’re seeing at Ford at elsewhere, was a big oops.

An interesting irony is that a post-CO₂ EPA may get into a refight of the 1960s “state’s rights” battle with California.

If you believe in Federalism, as the Project 2025 people say they do, you let the states take charge of their problems.

California’s current Advanced Clean Cars II plan is a policy that wants zero-emission new cars sales by 2035. It kicks off this fall with the 2026 models.

As at the Biden EPA, California’s plan is part industrial policy and part air pollution control.

How really necessary it is now for air quality control, I can’t say.

Although it’s interesting that CARB, the California Air Resources Board, recycles EPA-style claims that the plan “will provide public health benefits of at least $12 billion over the life of the regulations by reducing premature deaths, hospitalizations and lost workdays associated with exposure to air pollution.”

I think electric cars will come when they come. They can’t be ‘technology forced’.

But I can sympathize with a city like Los Angeles that has a smog problem encouraging people to drive EVs. The badly-polluted Chinese cities do that now.

Although Chinese electric cars are coal-powered.