An under-discussed hazard of being a student of history is I've seen this movie before syndrome:

There's a title on a streaming service that looks intriguing.

The Netflix recommendation engine is supremely confident — 98% — I'll love it.

Sounds promising, right?

Duh.

Because I did, when I watched it five years ago.

It can take me an embarrassing amount of time to realize I've seen a movie before.

Interestingly — to me, anyway — it usually requires a visual, such as an outdoor setting, to trigger it.

I don’t know what that says about how my brain works.

I try to put such worries out of mind.

Short-term memory a problem?

Fugget about it!

In politics I’m with Robert Bryce, who is fond of saying, “I’m not a Democrat. I’m not a Republican. I’m disgusted.”

At the moment, it’s impossible to escape media coverage of the US election campaign. Much as I’d like to avoid it.

Two weeks ago, the Washington Post quoted Donald Trump: “We’re going to have 10 to 20 percent tariffs on foreign countries that have been ripping us off for years.”

Kamala Harris came back a day later, claiming that particular Trump tariff idea would cost the typical American family $3,900 a year.

Harris and the Democrats have otherwise maintained a studied silence on the tariff — probably because the Biden administration not only kept Trump’s China tariffs, it added new ones.

American politicians wrangling over the tariff?

This movie I’ve definitely seen before.

The tariff is the oldest debate in American politics.

In fact, the tariff is the reason there is a United States of America.

Instead of 13 Dis-United States, or however many we would have now.

C.K. Chesterton said that if we’re truly interested in democracy, we should “giv[e] a vote to [that] most obscure of all classes, our ancestors.”

I’m not sure of correct tense here, but on the tariff, our ancestors have been there, done that.

I think they should get a voice. I’ve tried to give them one here.1

The tariff is but one part of the current US-China trade war.

The Historian likes putting dates on wars. A good one for the start of this one is July 6, 2018.

That’s the day the first of Trump’s tariffs went into effect. China announced retaliatory tariffs, on soybeans and cars, the next day.

So it’s been going on 6 years now.

In August, the Hong Kong–based South China Morning Post, which I like to look at for a sort of caught-in-the-middle China view on things, asked: “The US-China trade war has become a forever war, but at what cost?”

Good question.

The track record of the US in its other forever wars does not exactly inspire confidence in the ability of our politicians to win this one.

If they, or anyone, knows what winning looks like.

‘Trade war’ may be too simple a term for what is going on between Us and Them.

Some Washington national-security types talk about Cold War 2.0.

Into which, apparently, we’re sleepwalking, or already have sleepwalked.

The strategy used against our adversary in the previous Cold War involved decades of disengagement and containment.

By 1989, that seemed to work.

Although it’s entirely possible the former Soviet Union did itself in. The US national-security types like to take credit for such things.

Cold War 2.0 is not a comforting prospect. China is considerably stronger than the old Soviet Union. And the US economy a good deal weaker than it was in the 1980s.

So there’s also the word ‘decoupling’.

The US needs to ‘decouple’ its economy from China’s.

Noah Smith, the ubiquitous blogger, whose opinions on economics are about as difficult to avoid as the election coverage, wrote in October: “Decoupling isn’t just a geopolitical or military thing; it’s going to be one of the most important economic trends of the next couple of decades.’

Okay.

Couples getting a divorce, I suppose, are ‘decoupling’. This one looks to be pretty messy.

They say breaking up is hard to so.

In 2006, Niall Ferguson coined the word Chimerica to describe the hopelessly intertwined economies of China and America. The chimera was a hybrid fire-breathing creature in mythology.

At the time, Ferguson was most interested in a financial loop. The dollar-denominated proceeds from China’s export sales to the US were most readily parked in US Treasury notes. That enabled the US government to run larger budget deficits, bid up the dollar, and made Chinese imports cheaper. And repeat.

Aside: The traditional prescription for getting out of that loop is not anything a contemporary American politician wants to talk about. You reduce the deficit by spending less and — dare I say it — increasing taxes.

Both parties’ proclivities to spend — although especially the Democrats’ — have benefited from a new strain of voodoo economics, Modern Monetary Theory, which says deficits don’t really matter. The Republicans also cling to the Reagan-era ‘supply side’ thesis that tax cuts are self-financing.

We shall see. The federal government lays more in interest payments on the debt than it spends on veterans’ benefits, children, and Medicaid. That’s just today. It’s creeping up on education, defense, Medicare, and just about everything else.

In pop-psychology terms, Chimerica is a union of two deeply flawed codependents who were just made for each other. The United States consumes to excess; China produces to excess.

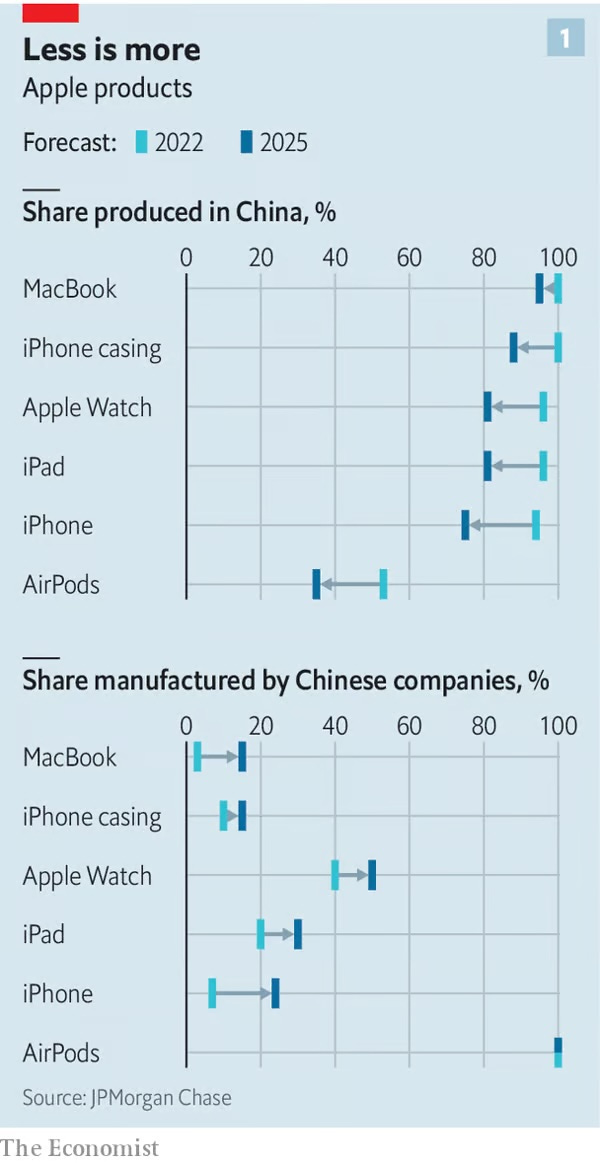

The Economist used a different relationship metaphor in a 2022 headline: "The end of Apple’s affair with China".

It’s going to take a while to call that one off:

Trump has a plan.

Sort of. And how realistic it is, I don’t know.

I speak as the neutral Historian here. High protectionist tariffs were the norm for the US during the 19th century, and long into the 20th. Trump’s high tariffs would be a return to that earlier era.

Protectionist tariffs have always come with some flag-waving and a large dose of economic nationalism. Henry Clay put the case eloquently around 1820:

We should not have subverted a patriotic system of domestic protection … for the visionary promises of an alien policy of free trade, fostering the industry of foreign people and the interests of foreign countries, which has brought in its train disaster and ruin to every nation that has had the temerity to try it.

Biden’s approach to the US-China trade war includes not just the tariffs but scatter-shots of industrial policy, especially his green industrial policy.

To Biden’s fans, the scatter-shots are strategic. To others, they’re kind of everything-bagel.

Industrial policy is also not new for the United States. But that coming in Part II. So

As a teaser, the Historian notes that the plan for new-nation industrialization used so successfully after World War II by Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China was invented in the USA, by Alexander Hamilton.

In 1791. Before he became a Broadway star.

Let’s start with the tariff.

Since we’re channeling voices from history, fair warning:

Daniel Webster called the tariff a “tiresome, disagreeable subject.”

“The people,” Illinois Congressman William Morrison lamented in 1882, “do not understand the question, and it is too hard a study for them.”

William Howard Taft, later a chief justice of the Supreme Court, confessed to being “bewildered by the intricacies of the tariff measure.”

After a presentation on the tariff, Harry Truman said, “I don’t know anything about these things. I certainly don’t know what I’m doing about them. I need help.”

A tariff is a tax.

An import duty is paid by an importer at the port of entry. That money goes straight into the US Treasury.

The China trade war tariffs have put around $233 billion into the US Treasury since 2018, roughly $79 billion a year.

As a tax, that’s not entirely insignificant.

Tariffs as taxes are well-known to be regressive. A liberal-ish think tank, the Tax Policy Center, calculates that for certain low-income US families the ‘China tariff tax’ has reversed any benefit they got from Trump’s tax cut in 2017.

Trump has, in that way Trump does, floated the idea that tariffs on imports could allow the income tax to be eliminated.

Which, the Historian is duty-bound to point out, was the way it was for the US during its first 125 years:

In fact, at numerous points, the high protective tariffs of the late 19th century produced too much revenue. A budget surplus was the problem.

Aside: Quickly solved. It was a good time to be a Civil War veteran. Or the widow or orphan of a Civil War veteran. Eventually, a distant relative of a Civil War veteran.

In the first decade of the 20th century, the Progressive (capital ‘P’) campaign for a progressive (small ‘p’) income tax was based on the argument that it would be more fair than the regressive tariff.

An importer almost always adds the import duty onto the price he or she is asking US customers to pay.

Thus the US purchaser of the imported good pays the tax. Not the foreign country. Only rarely do foreign manufacturers ‘eat’ a tariff by lowering their prices.

So far, it’s simple:

The higher-priced imported item should stick out like a sore thumb in the commercial landscape.

Consumers can, if they prefer, choose a lower-price domestic alternative, assuming there is one.

That’s the theory.

In reality, domestic producers usually use the higher ‘tariff-burdened’ price their competitors must charge as an excuse to raise their own prices.

That increment goes to the domestic producer, not the US Treasury. A very solid reason why tariffs have popular with the business community.

One US president, Grover Cleveland in 1888, made a valiant effort to explain the cost-increase effect in words the public could understand:

So it happens that while comparatively a few use the imported articles, millions of our people, who never used and never saw any of the foreign products, purchase and use things of the same kind made in this country, and pay therefor nearly or quite the same enhanced price which the duty adds to the imported articles.

Those who buy imports pay the duty charged thereon into the public Treasury, but the great majority of our citizens, who buy domestic articles of the same class, pay a sum at least approximately equal to this duty to the home manufacturer.

I decided I needed the wisdom of Grover Cleveland in my own life.

Take whatever it was he just said there, and make it personal.

An item I use as an inflation indicator are those rectangular 12-can packs of Coke or Pepsi:

Even with my short-term memory problem, I can remember when you could pick those up on sale for $3.

Last time I looked at the store, the list price was $9.49.

What’s going on with that?

At least one thing that’s going on is the aluminum tariff.

Last I looked, the tariff on Chinese aluminum — but no longer on Canadian or Mexican — was 10%.

But according to a White House Fact Sheet dated May 14, 2024: “The tariff rate on certain [Chinese] steel and aluminum products … will increase to 25% in 2024.”

Now, we could ask the White House to be more specific about which certain steel and aluminum products it’s talking about.

But history counsels us to be careful what we ask for.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930 enumerated rates on 3,295 items in mind-numbing detail:

Bottle caps of metal, collapsible tubes, and sprinkler tops, if not decorated, colored, waxed, lacquered, enameled, lithographed, electroplated, or embossed in color, 30 per centum ad valorem; if decorated, colored, waxed, lacquered, enameled, lithographed, electroplated, or embossed in color, 45 per centum ad valorem.

The floor debate on that bill took 527 hours and filled 2,638 pages of the Congressional Record.

A single House member’s speech, about tomatoes, went on for 15 pages.

Now, before you ask: Why, yes. I recycle aluminum cans.

Or did, when I could afford to buy them.

That’s because aluminum cans are one of the few things it actually makes economic sense to recycle.

Although I have to drive the empties to the town recycling center myself.

I live in a red state, where curbside recycling is viewed as a slippery slope to Communism.

The town recycling center employs — what am I allowed to say? — challenged youth. I’m glad they’ve got jobs.

Anyway, curbside recycling is not without drawbacks.

Back in my former blue state, a friend who lived in a very status-conscious suburb took time to artfully arrange the empty wine bottles in her curbside bin on pickup day.

Empties from the most expensive varietals were casually displayed on top.

That was so the neighbors walking their dogs wouldn’t sniff out the plonk hidden beneath.

‘Secondary’, or recycled, aluminum is actually a big deal.

Recovering aluminum from scrap takes of 5% the energy needed to make ‘primary’ aluminum from bauxite ore.

Aside: 5% percent, by the way, is the answer to a perennial AP Chemistry exam question. Sadly, the exam asks you to back up your number with calculations. You can copy those from here.

My having to haul my empties is but a small sacrifice.

During World War II, you were asked to bring in your kitchen pots and pans. Here’s the start of an aluminum-collection ‘party’ that was broadcast live from New York in 1941:

Secondary aluminum now accounts for 78% of US aluminum production.

Which leads to some Fun Facts about aluminum cans:

The shiny ‘new’ can you buy at the store is mostly secondhand.

The aluminum in the cans I haul down to the recycling center can be back on your store shelf in as little as 60 days.

Primary aluminum production in the US has fallen on hard times.

Today, the US produces 1.1% of the world’s primary aluminum. Its share for secondary aluminum is more respectable at 9.4%,.

The US peaked in 1980 and has gone downhill ever since. It became a net importer of aluminum in 1999.

At the moment, four primary aluminum smelters remain inside the borders of the United States.

But there are plenty more just across it, in Quebec.

If you don’t count the calories, the aluminum can is the most expensive thing that goes into — or around — a can of beer. That cost is in the neighborhood of 12%.

5.2% of the aluminum imported into the US comes from China. Canada provided 52.6%, as of the fourth quarter of 2023.

If you start doing the numbers, a 10% tariff on 5.2% of 12%….

I give up. But it doesn’t seem like much.

Here’s where we need to turn to the wisdom of Grover Cleveland.

A tariff is an excuse, an opportunity, to raise prices.

The Beer Institute is one of the oldest industry associations in the United States.

The United States Brewers' Association was organized in 1862 in New York by German immigrant brewers to protest a tax the Union had put on a beer.

The term ‘lobbyist’ also dates back to General Grant’s time. The story goes that when President Grant would have one of his cigars with a brandy at the Willard Hotel, its lobby would fill up with those trying to get in a word.

On July 1, 2022, the CEOs of Molson Coors, Anheuser-Busch, Heineken USA, and other companies in the Beer Institute wrote President Biden a letter complaining that “the American beverage industry has paid more than $1.4 billion in Section 232 aluminum tariffs since 2018.”

Of that, says the Beer Institute, 7%, or $126 million, actually went to the US Treasury.

The remainder, according to the Beer Institute’s calculations, came from the Grover Cleveland effect.

Specifically, a US company that wants to buy aluminum — if it doesn’t have a long-term contract with some Canadian supplier, which most do — gets quoted a price that includes something called the US Midwest premium.

That premium is added onto the London Metals Exchange (LME) global baseline price, giving the going US price for aluminum.

Whether it entered duty-free from Canada; came from China and was subjected to the tariff; or was recycled out of my old cans.

The US Midwest premium is calculated by Platts, a subsidiary of S&P Global.

The Beer Institute won’t quite come out and say it, but appears to believe Platts’s ‘opaque’ process for computing the US Midwest premium invariably reflects the highest, ‘tariff-burdened price’.

The Beer Institute has other allies against the aluminum tariff.

The Aerospace Industries Association, which represents major defense firms, is against it. “Our industry employs 2.4 million people and produced a trade surplus of $86 billion last year,” said Eric Fanning, AIA’s president in 2018. “Tariffs on aluminum and steel would jeopardize that surplus and put those jobs at risk.” The tax on aluminum alone, Fanning added, “would create almost $2 billion in unnecessary costs to U.S. manufacturing.”

One surprise is that even Alcoa — the largest primary aluminum producer in the US — was against aluminum tariff. At least when it tariffed imports from Canada and Mexico.

19th century thinking about the tariff did not have to deal with supply chains of intermediate goods criss-crossing national boundaries willy-nilly. Those interwoven supply chains are a distinctly late 20th century development.

Alcoa has a lot of those. It considered the effect of the tariff on all its lines of business and said no thanks.

There were good fights in the 19th century on a closely related topic, tariffs on raw materials.

High prices on raw materials work their way up the manufacturing chain, increasing the price of everything that uses them.

Pennsylvania Congressman William “Pig Iron” Kelley is one of my favorite characters, if only for his name.

Kelly worked tirelessly on behalf of his constituents to make sure tariffs kept foreign pig and bar iron more expensive than the Pennsylvania version.

The price of goods subsequently made from iron, Kelley said, was not his problem.

If those manufacturers wanted tariffs protecting their items, they could lobby for them.

Which they did.

In 1903, Edward Stanwood wrote a book called American Tariff Controversies in the Nineteen Century. He summarized:

Washington had come to be filled with as fine a band of plunderers as ever besieged a National Congress: tax swindlers, smugglers, speculators in land grants, railroad lobbyists, agents of ship companies, mingled with the representatives of industries seeking protection, until it seemed as if Congress was little more than a Relief Bureau.

It was not a forgone conclusion that the new American Republic would have a tariff at all.

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations was published in the seminal year, 1776.

The Founders had all read it.

Thomas Jefferson gave it a five-star review: “In political economy, I think Smith’s Wealth of Nations is the best book extant,” he wrote a correspondent in 1790.

‘Free trade’ was a new and vaguely subversive idea at the time.

Not long since, the European concept of international trade, as practiced by likes of the Vikings and Sir Frances Drake, had been targeting some coastal village and subjecting it to pillage, plunder, and rape.

As for the The Wealth of Nations, everyone knew the wealth the Spanish Empire derived from rapine. It had grabbed the Aztec silver and the Inca gold out of the Americas.

Europe had evolved slightly, but trade was still very much a power thing, not exactly consensual. That’s why Britain spent so much on its Navy.

The American founders’ sympathies were with Smith and his fellow English economic liberals.

The English liberals were up against an entrenched land-owing aristocracy. It had Parliament in its pocket boroughs.

The British Corn Laws were a infamous cluster of special-interest import quotas and tariffs on wheat.

Aside: ‘Corn’ referred to wheat, oats, and barley, not American corn or maize.

The Corn Laws were guaranteed to keep the price of wheat artificially high for the benefit of the landed gentry.

Even when everybody else was hungry and could’t afford to buy the bread made from that wheat.

Aside: It took the scandalous starvation in Ireland to finally get the Corn Laws repealed in 1846.

So the Founders leaned toward Smith.

“It is perhaps an erroneous opinion,” Benjamin Franklin wrote in 1781, “but I find myself rather inclined to adopt that modern one, which supposes it is best for every country to leave its trade entirely free from all encumbrances.”

That was the ideal, anyway.

But, as ideals do, it had to be tempered with realism.

Trade takes two in the tango.

Thomas Jefferson said in an ideal world, the new nation could start out by

throwing open all the doors of commerce and knocking off all its shackles. But as this cannot be done for others, unless they do it for us, and there is no probability that Europe will do this, I suppose we may be obliged to adopt a system which may shackle them in our ports, as they do us in theirs.

Hamilton was even more Realpolitik. If free trade was such a good idea, why wasn’t any other country doing it? As an idea, it was

contradicted by the numerous institutions and laws that exist everywhere for the benefit of trade, by the pains taken to cultivate particular branches and to discourage others, by the known advantages derived from those measures, and by the palpable evils that would attend their discontinuance, it must be rejected by every man acquainted with commercial history.

In any event, the new United States had no choice but to go with a tariff.

United States 1.0, under of the Articles of Confederation, was broke.

A very prime motive for the Constitutional Convention of 1787 was to fix that.

Among the powers of Congress, the tariff got pride of place in Article I of the new Constitution. “Taxes on imports [were] the only sure source of revenue,” explained John Rutledge, head of the committee that drafted it.

When Congress met for the first time, the Tariff of 1789 was the first serious law it passed.

Congress was in a hurry the get the tariff passed and some coin rolling into the Treasury .

But Congress spent a lot of time arguing about it. Which would be a recurring pattern.

There was the North-South split.

The South had to trade its agricultural products — at the time, mainly cotton and tobacco — for ‘Manufactures’ from Europe. It wanted a minimal tariff on those imports.

The North, especially Hamilton, was thinking it might want to have ‘Manufactures’ of its own someday. High tariffs would protect those ‘infant’ industries from British and European competition.

That time around, the South had the votes. The First Congress could agreed only on a basic ‘tariff for revenue.’

The division over the tariff would continue up to — and in some part cause — the Civil War.

New England finally got the ‘Manufacturers’ Hamilton had wanted.

Not by government policy. They proved to be a happy unintended consequence of a fiasco, the War of 1812.

Aside: Andrew Jackson’s victory in New Orleans came after the buzzer, so doesn’t really count.

Cut off from Britain and Europe, domestic manufacturing finally got going.

In presenting the peace treaty to Congress in February 1815, Madison, then president, asked Congress to consider the “means to preserve and promote the manufactures which have sprung into existence, and attained an unparalleled maturity throughout the United States, during the period of the European wars.”

The first protectionist tariff, of many to come, was passed by Congress in 1816.

The tariff debate usually plunged Congress into a fever swamp of jingoist grandstanding.

After one such session, Daniel Webster in complained privately to a friend: “The House [is] apparently insane.”

Those seeking lower tariffs were either delusional dreamers or traitors, conspiring with the British to destroy our innocent infant industries.

The jingoists had proof, of sorts. An MP named Henry Brougham had suggested to the House of Commons that “it [may] well [be] worthwhile to incur a loss upon the first exportation, in order, by the glut, to stifle in the cradle those rising manufacturers in the United States which the war had forced into existence contrary to the natural course of things.”

The original appearance of the concept of ‘dumping’. Dumping is selling substantially below cost.

Selling below cost is not, in itself, illegal.

In market capitalism, that can happen from time to time.

Legally, it requires ‘predatory intent’ for dumping to be either downright illegal, or worthy of being denounced as evil.

The problem is that establishing intent, as might be done in a trial, is a lot of work, especially the intent of foreigners, who are distant.

The jingoists simplified matters and just presumed them guilty.

Protectionism always had the best memes. Economic jingoism had an “advantage on catch words,” William Morrison put it in 1882.

‘Flooding our markets’ became a standard trope in protectionist rhetoric. Congressman Joseph Fordney in 1921: “flooding our markets with cheap foreign goods, closing our mills, throwing our labor out of employment and mortgaging our farms.”

Aside: Still around. A White House fact sheet from May 14, 2024: China is “flooding global markets with artificially low-priced exports.”

The tariff is a classic example of policy with concentrated benefits and diffuse costs.

The beneficiaries were easy to find. And vocal.

A domestic manufacturer who wanted ‘protection’ from his foreign competitors had no problem getting the ear of his representative in Congress.

Only a few US presidents, such as Grover Cleveland and Woodrow Wilson, argued the side of the general public, which bore the diffuse costs of the tariffs in higher prices.

Alas, the subject was “to hard a study.” And the public had no lobby.

The first cracks in the protectionist paradigm finally started to appear in the 1890s.

Before 1890, American exports had been dominated by the usual agricultural commodities — cotton, wheat, corn, meat.

In the last decades of the 19th century, US manufacturing took off almost exponentially.

As did exports of US manufactured goods. They jumped to 35% of total exports by 1900 and hit 50% in 1913.

Exporting now had a lobby.

In 1908, Andrew Carnegie, somewhat to the outrage of the protectionists in Congress, testified that the US iron and steel industry was well past being an ‘infant’ industry.

It could fend for itself now, thank-you very much, without fear of foreign competition. It no longer needed a tariff to protect it.

What Congress needed to do, Carnegie said, was help American manufacturers increase their exports. The US tariffs should be used as bargaining chips. Get foreign nations to reduce theirs.

That was a bit hard for Congress to take. The steel industry was a fabled Guided Age success story of American industry.

Aluminum came a little late to the party, but had a similar story.

Before 1886, aluminum had been a luxury metal, more expensive than silver.

Napoleon III — or his baby — had a rattle made out of the stuff:

Napoleon III’s very special dinner guests got to eat off the aluminum plates.

In 1884, a small pyramid of aluminum was placed at the tip of Washington Monument as a lightening rod. No expense was spared in honoring George. Here’s Spider Man caressing it for its special powers:

In 1886, Charles Martin Hall, a 22-year-old chemist in Ohio, figured out how to separate pure aluminum by electrolysis out of a nasty sulfureous soup. The company Hall started eventually became Alcoa.

A French inventor, Paul Héroult, came up with the same process independently.

In technology, simultaneous discoveries like that happen when the time is ripe.

Electricity enabled aluminum. Electricity still accounts for 40% of the cost of producing primary aluminum from bauxite ore.

The rise of Alcoa is the happy arc of the success story. The fall from grace will come in Part II.

After Hall’s breakthrough, all sorts of uses for now-inexpensive metal were found.

The Wright Brothers' flyer got off the ground in 1903 because its engine block was cast in aluminum.

By World War I, Alcoa alone produced 63% of the world’s aluminum.

And produced it all over the world. Aluminum smelters popped up wherever electricity was cheap.

That landed the industry in some unlikely places, such as Norway and Iceland.

Both had hydropower to spare. As did Quebec. About 90% of Canadian aluminum is smelted there.

US primary aluminum smelters, now largely gone, clustered around the Bonneville Power Administration in Washington state and the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Aside: We’re become accustomed to thinking about industries moving to low-wage countries.

We need to think much more about industries migrating to, or staying in, high-energy countries.

The apotheosis of protectionism came in the 1930s.

In response to the financial crisis, nations tried anything — state subsidies, high tariffs, currency devaluation, anything — to get production going again.

It took World War II to really do that.

After the War, the economic nationalism of the 1930s was seen as major culprit and contributor to the war.

International trade needed to be encouraged. Tariff barriers need come down.

Multi-nation custom unions, such as the forerunners of the European Union, were intentionally knit together of former adversaries so they wouldn’t fight again.

For the United States, free trade was easy to love after World War II. It was the dominant export power.

That would change.

And it was all Alexander Hamilton’s fault.

But that’s coming in Part II.

Most of the quotes can found in Douglas A. Irwin’s excellent — if long — 2017 book, Clashing Over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy, originally published by The University of Chicago Press. Highly recommended if you have some time to spare.